They now constitute about only 2% of Mexico`s total population and numbering about 900,000.

Afro-Mexican boy and girl performing traditional dance, Mexico

This paltry figure of blacks in Mexico is shocking because as University of Minnesota demographer Robert McCaa wrote, "Afro-Mexicans, who numbered one-half million in 1810, more or less vanished, thoroughly intermingled and unidentifiable by 1895 if the official discourse is accepted at face value."

In Terms of History of Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, the early African presence in the Americas is normally associated with the slave trade in the United States, the Caribbean, Brazil, Central America, Colombia and Peru. What is not generally taught in history textbooks is that Mexico was also a key port of entry for slave ships and consequently had a large African population. In fact, during the colonial era, there were more Africans than Europeans in Mexico, according to Aguirre Beltrán's pioneering 1946 book, "The Black Population in Mexico." And he said they didn't disappear, but in fact took part in forging the great racial mixture that is today Mexico. "Because of race mixture, much of the African presence is no longer discernible except in a few places such as Veracruz and the Costa Chica in Guerrero and Oaxaca," wrote Aguirre Beltrán.

Afro-Mexican woman holding her daughter at La Coast Chica in Oaxaca, Mexico. http://zkahlina.ca/

What most people do not know is that Afro-Mexicans were the first enslaved Africans in the Latin America to form the first community of free blacks. This settlement called Yanga (formerly San Lorenzo de los Negros) was formed out of the rebellion which occurred in Veracruz in 1537. Runaway slaves (cimarrones), who mostly fled to the highlands between Veracruz and Puebla with others made their way to the Costa Chica region in what are now Guerrero and Oaxaca. The Runaways in Veracruz formed settlements called “palenques” led by the famous Gaspar Yanga (Nyanga), a Gabon slave who fought off Spanish authorities for forty years until the Spanish recognized their autonomy in 1608, making San Lorenzo de los Negros (today Yanga) the first community of free blacks in the Americas.

Statue of Afro-Mexican leader and Mexican National Hero Gaspar Yanga. He was slave rebel that formed the first free black community (palenque) in Latin America known as Yanga. Today, the town reportedly hosts the "Carnival of Negritude" every August 10th in honor of Gasper Yanga

The existence of blacks in Mexico is deliberately made unknown, denied or diminished in both Mexico and abroad for a number of reasons: their small numbers, heavy intermarriage with other ethnic groups and Mexico’s tradition of defining itself as a “mestizaje” or mixing.

Afro-Mexicans

What many ignorant racist and avid supporters of ""mestizo" people -- a mixture of Spaniards and Indians -- officially referred to as "La Raza" or "The Race, do not know is that the early Mexican governments appreciated the role of Africans in their independence struggles and abhorred any form of slavery thereby given sanctuaries to runaway slaves from United states. "Colonial Mexico had the highest numbers of African slaves. Of the over one million casualties during the Mexican war of independence, most of them were Afro-Mexicans. It was in the view of this that Mexico’s commitment to harbor Black fugitive slaves triggered the Mexican-American war; which Mexico lost nearly 50 percent of her territory. After the war, Mexico undeterred, included in her constitution and continued her commitment to harbor fugitive slave."

Actress Stacy Dash, is an Afro-Mexican (Her ancestry comprises Mexican is part Barbadian, and African American)

In fact, when in 1857 James Frisby, a “Negro” seaman jumped ship in Veracruz and claimed to have been a slave in New Orleans “whose master had signed him on board the Metacomet as crew;” the port captain refused to turn him over. U.S. Representative in Mexico John Forsyth resorted to arm-twisting Mexico even to the point of declaring that Mexico extended a privilege to the seaman because of the “ebony color of his skin.” Forsyth berated Mexico for letting a Black get away with what those of “pure white blood … the master blood of the earth … blood which has conquered and civilized and Christianized the world.” Forsyth in his rage declared, “If Mexico is so deeply imbued with the mania of negrophilism [love of “Negroes”] … imprisoning our White Citizens and making free our Slaves, as fast as they put foot on Mexican soil, cannot long endure consistently with peace and harmony between the two countries.” Forsyth failed to intimidate Mexico, and she remained adamant in her defense and protection of fugitive Black slaves.

Afro-Mexican man

The real history of Mexico which now pride itself as a "mestizo" people -- a mixture of Spaniards and Indians -- officially referred to as "La Raza" or "The Race," is that African ancestors were on the Mexican land even before the Mayan and Aztec civilization. The Olmec civilization (1200-400 BC) which was founded by Africans and had its capital in La Venta in Mexico affirms a prolonged presence of African ancestors who laid the ancient foundation of America long before Christopher Columbus’ great, great, great, grandfather whom Mexicans claim to have mixed ancestry with was born. Columbus is said in European history to have discovered America in 1492.

Afro-Mexican dancing group from Yanga, Mexico

Without going deep into Olmec civilization and African presence in America before Columbus, it must be emphasized that the first blacks (Africans) to have landed in Mexico were free men (Moors) from Spain, who came along with the Spanish Conquistadors and explorers. Later, many slaves were imported from Africa through the Portuguese slave traders. These dark skinned slaves "the first true blacks were extracted from Arguin," i.e Maure people of Anguin in Mauritania, West Africa. In the sixteenth century black slaves (Africans) were also brought from Bran (Bono, and other Akan people of Ghana and Ivory Coast), biafadas (Mandika and other Senegambians), Gelofe (Wolofs of Cape Verde) and later Bantu people were also extracted from Angola and Canary Islands. Other blacks from United States also fled from slave states to seek sanctuary in Mexico. In fact, in the summer of 1850, the Mascogos, composed of runaway slaves and free blacks from Florida, along with Seminoles and Kikapus, fled south from the United States, to the Mexican border state of Coahuila. Accompanying the Seminoles were also 'Black Seminoles' -- slaves who had been freed by the tribe after battles against white settlers in Florida. The three groups eventually settled the town of El Nacimiento, Coahuila, where many of their descendants remained.

Afro-Mexicans in Costa Chica. Courtesy alexisokeowo.wordpress

“Colonial records show that around 200,000 African slaves were imported into Mexico in the 16th and 17th centuries to work in silver mines, sugar plantations, and cattle ranches. But after Mexico won its independence from Spain, the needs of these black Mexicans were ignored. Some Afro-Mexican activists identify themselves as part of the African diaspora. It was clear from colonial records that the black population in the early colony was by far larger than that of the Spanish. In 1570 the black population was about 3 times that of the Spanish. In 1646, it was about 2.5 times as large, and in 1742, blacks still outnumbered the Spanish. It is not until 1810 that Spaniards are more numerous.

Below: is table of steadily growth and decline of African in Mexico between 1570-1742

Population Estimate of Colonial Mexico

| 1570 | 1646 | 1742 | |||||

| Europeans | 6644 | 0.20% | 13780 | 0.80% | 9814 | 0.40% | |

| Africans | 20569 | 0.60% | 35089 | 2.00% | 20131 | 0.80% | |

| Indígenas | 3366860 | 98.70% | 1269607 | 74.10% | 1540256 | 62.10% | |

| Euro-Mestizos | 11067 | 0.30% | 168568 | 9.80% | 391512 | 15.80% | |

| Afro-Mestizos | 2437 | 0.10% | 116529 | 6.80% | 266196 | 10.70% | |

| Indo-Mestizos | 2435 | 0.10% | 109042 | 6.40% | 249368 | 10.10% | |

| Total | 3411582 | 100.00% | 1712615 | 100.00% | 2479019 | 100.00% | |

Afro-Mexicans and Gene pool of Mestizo

So what happened to the reduction of African population? The answer is that, the Africans committed themselves to fight the Mexican wars of independence that freed mexico from the shackles of the Spanish imperialists. " Hundreds of thousands died in the war of independence fertilizing Mexican soil, the rest has been absorbed in the genetic pool of the Mexican mestizo" (Diogenes Mohammed, 2014). It must be emphasized here that out of over one million casualties during the Mexican war of independence, most of them were Afro-Mexicans. Again many years and generations of intermarriage, discrimination against blacks making more blacks of mixed ancestry to identify themselves as either Mestizo or white culminated in no more than 2 percent of the Mexican population identifying themselves as blacks or moreno (brown).

Kalimba Marichal, Afro-Mexican singer and actor

Despite the fact that Afro-Mexicans have a small population, the truth however, is that most of the so-called Mestizo or "La Raza" ("The Race") or white Latinos of Mexico have more black ancestry in their gene pool than they ever know. During the war of independence 1810- 1821, about 30 to 40 percent of mixed race Mexicans had African in their mix and were more likely to be militant.

The apparent assimilation of Mexico's ex-slaves into the overall gene pool is in marked contrast to America's experience, where the black race has remained relatively distinct. In the average self-declared white American's family tree, there is only the equivalent of one black out of every 128 ancestors, according to the ongoing research of molecular anthropologist Mark D. Shriver of Penn State University and his colleagues.

In fact, Mexico even differs from the rest of Latin America, where distinct black populations remain genetically unassimilated. "Mexico is unique in this regard," commented population geneticist Ricardo M. Cerda-Flores of the Mexico's Autonomous University in Nuevo Leon.

Cerda-Flores' team found that a sample of Mexicans living around Monterrey in Northeast Mexico averaged around 5 percent African by ancestry, according to its genetic markers. In other words, if you could accurately trace the typical family tree back until before the first Spaniards and their African slaves arrived in Mexico in 1519, you would find that about one out of twenty of the subjects' forebears were Africans.

Cerda-Flores and his colleagues also examined the DNA of Mexican-Americans in Texas, who came out as about 6 percent black. Other studies of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans by molecular anthropologists have come up with black admixture rates ranging from 3 percent to 8 percent.

Afro-Mexican girl in Costa Chica

By way of contrast, this appears to be, very roughly, something like half of the black ancestry level of the overall American population, as implied by Shriver's studies. Of course, most of the African ancestors of Americans are visibly concentrated among African-Americans, who average 82 percent to 83 percent black, according to Shriver. Among Mexicans, however, African genes appeared to be spread more broadly and evenly.

Recently, Mexican-American TV host and comedian George Lopez was handed his DNA ancestry results by Mariah Carey – after the question was posed as to whether he would fall under the proverbial one-drop (African) racial classification. Lopez’s results showed a 4 percent African blood. “Texican” actress and a member of hit TV series Desperate Housewives, Eva Longoria’s 3 percent African ancestry surfaced in DNA taken by PBS series Faces of America (Henry Louis Gates, Jr.). And National Geographic’s Genographic Mexican-American reference population attributes a 4 percent African contribution to the “La Raza” pool. The “Mestizo” – the proverbial “La Raza” Mexicano – customarily extols his Indian roots, and laments and or praises his Spanish roots – but rarely is the African part acknowledged.

AfroMexican women standing in front the Hotel Marin in the town of El Ciruelo, Oaxaca

Nevertheless, the official ideology of Mexico has been that the Mexicans are simply a "mestizo" people -- a mixture of Spaniards and Indians -- officially referred to as "La Raza" or "The Race." Since 1928, Mexico has celebrated Oct. 12 as "The Day of The Race." On Oct. 12, 1946, Mexican politician José Vasconcelos famously declared mestizos to be "the cosmic race."

However, the existence of Afro-Mexicans was officially affirmed in the 1990s when the Mexican government acknowledged Africa as Mexico’s “third root”. The Mexican populace's African "third root" is occasionally honored, but Mexican officials have generally ignored it. In fact, the black contribution to Mexico's "cosmic race" has been so forgotten that in last November's race for governor of the state of Michoacán, Alfredo Anaya of the former ruling party PRI hammered away at his opponent Lázaro Cárdenas, the scion of Mexico's most famous leftist dynasty, for having a part-black Cuban wife and son.

Anaya argued, "There is a great feeling that we want to be governed by our own race, by our own people."

One of his supporters said, "It's one thing to be brown. The black race is something different."

Ultimately, this strategy failed, as Anaya lost. Still, he came within five percentage points of beating the son of Cuauhtemoc Cardenas, the man who is widely believed to have been cheated out of Mexico's presidency in 1988 by massive PRI vote fraud. Further, this Lázaro Cárdenas is the grandson of the Lázaro Cárdenas, Mexico's most popular president, who is still adored for triumphing over the United States by nationalizing American-owned oil companies in 1938. So, considering the vast name recognition enjoyed by Cardenas, Anaya's pro-mestizo and anti-black ploy cannot be dismissed as wholly ineffectual.

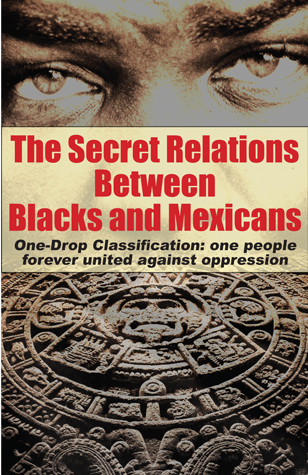

As a Roberto Rodriguez and Patrisia Gonzales sagely wrote in their article in "Chronicle Features" in 1996, "In times of racial discord between Latinos and African Americans, this historical confluence of cultures should serve as a reminder that both communities share common ancestors. In fact, if we probe far enough, we're all related."

Afro-Mexican contributions

Though African-descended people have been a part of Mexican history from the very beginnings of the colony, but life can be difficult for black Mexicans, because they are often assumed to be illegal immigrants from elsewhere in Latin America, such as Panama. The Mexican police often treat illegal aliens harshly. Mexico's obliviousness to its black roots is slowly changing.

Throughout the centuries, Afro-Mexicans have made enormous contributions to the country and deserve recognition for their many accomplishments. Afro-Mexicans share a rich history and count heroes and presidents amongst their ancestors.

Vicente Guerrero, Afro-Mexican, abolitionist, war hero and second president of Mexico

Vicente Guerrero, a mulatto and Mexico`s 2nd president, was a hero in Mexico`s War of Independence from Spain. The state of Guerrero in Mexico was named in his honor. His grandson, Vicente Riva Palacio y Guerrero, was one of Mexico`s most influential politicians and novelists. In addition, one of the most prestigious generals in Mexican`s War of Independence, Jose Maria Teclo Morelos y Pavon, was a mulatto as well.

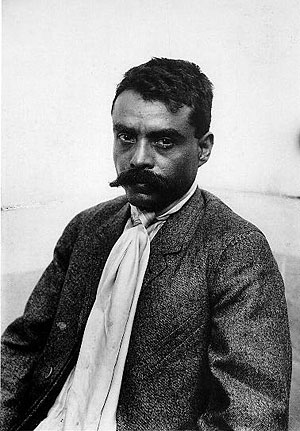

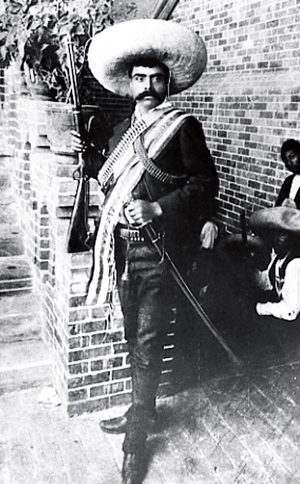

Afro-Mexican Emiliano Zapata was perhaps the noblest figure in 20th century Mexican politics, a peasant revolutionary still beloved as a martyred man of the people. Although Marlon Brando played him in the 1952 movie "Viva Zapata!" the best-known photograph of the illiterate idealist shows him with clearly part-African hair. His village had long been home to many descendants of freed slaves.

Statue of Morelos at Janitzio, Michoacan. osé María Teclo Morelos y Pavón (September 30, 1765, Valladolid, now Morelia, Michoacán – December 22, 1815,San Cristóbal Ecatepec, State of México) was an Afro-Mexican priest and revolutionary rebel leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of Miguel Hidalgo in 1811. He was later captured by the Spanish colonial authorities and executed for treason in 1815.

Afro-Mexicans have also greatly contributed to Mexico`s rich heritage of dance, music and song. The famous carnival celebrated in Coyolillo in Veracruz has African origins. Mexico`s food, language and spiritual practices have been influenced by the descendants of black slaves. Black immigrants to the country must be recognized and included in this equation as well.

Afro-Mexican Emiliano Zapata

Mexican music, for example, has deep roots in West Africa. "La Bamba," the famous Mexican folk song that was given a rock beat by Ritchie Valens and a classic interpretation by Los Lobos, has been traced back to the Bamba district of Angola.

Colonel Carmen Amelia Robles Avila, an Afro Mexican woman who was a leader in the Mexican Revolution. She fought alongside Emiliano Zapata. Legend has it that she participated in many battles and that she would shoot her pistol with her right hand and hold her cigar with her left. Although many knew she was a woman, people generally referred to her, in the masculine, as Amelio Robles.

Language

Afro-Colombians speak Spanish and can be found in certain parts of Mexico such as the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero, Veracruz and in some cities in northern Mexico.

Governor Pío Pico, Afro-Mexican politician and the last governor of Alta California (now the State of California) under Mexican rule.

History

For the purposes of Blacks that came to Mexico as a result of Slavery, this historical accounts of Olmec civilization of African presence in America is omitted.

Afro-Mexicans were first brought by the Spanish Conquistadors and explorers. These blacks (moors) were from Spain and did not arrived in any slave ship. They were free men whilst some them were also personal servants of their Spanish masters. One of the earliest Africans brought to Mexico is said to be Juan Garrido, a free man who probably took part in the “Conquest” led by the famous Spanish Conquistador Hernán Cortés in 1519. Another of these early arrivals was Estebanico, a slave who took part in various expeditions in the 1520s and 1530s, including treks through what is now Florida, Texas, and New Mexico.

The slave trade that changed the demographic face of Mexico began when King Carlos V began issuing more and more asientos, or contracts between the Crown and private slavers, in order to expedite the Trans-Atlantic Trade. At this point, after 1519, the New World received bozales, or slaves brought directly from Africa without being Christianized. The Spanish Crown would issue these contracts to foreign slavers, who would then make deals with the Portuguese, for they controlled the slave posts on the West African coast. In addition, the Crown would grant slaving licenses to merchants, government officials, conquistadores, and settlers who requested the privilege of importing slaves to the Americas.

The crown granted the right for importation of slaves following the devastation brought about by the inherent diseases of the Europeans, which infected and almost completely wiped out indigenous Mexicans. Having no natural immunity against smallpox, measles, typhoid, venereal diseases and other infectious maladies, natives were victims of ferocious epidemics in 1520, 1548, 1576-1579, and 1595-1596. Another Spanish conquistador, Pánfilo de Narváez, is said to have brought an African slave who was blamed for the smallpox epidemic of 1520.

Pay day for African American and Mexican workers, ca. 1930s.

It is estimated that when Conquistador Hernan Cortes arrived in Mexico in 1519, the indigenous population was about 27.6 million inhabitants. By 1605 only 1.7 million indigenous people had survived, a population decrease mulattoes; 15,000 Spaniards, and 80,000 Indians. Slaves were therefore imported from Africa through the Portuguese slave traders to replace the disappearing indigenous Indians. These dark skinned slaves "the first true blacks were extracted from Arguin," i.e Maure people of Anguin in Mauritania, West Africa. In the sixteenth century black slaves (Africans) were also brought from Bran (Bono, and other Akan people of Ghana and Ivory Coast), biafadas (Mandika and other Senegambians), Gelofe (Wolofs of Cape Verde) and later Bantu people were also extracted from Angola and Canary Islands. Soon the Mexico had a lot of black workforce. Blacks slaves were classified into several types, depending on their abundance, origin and mostly physical characteristics. The first, called Retintos, also called swarthy, came from Sudan and the Guinea Coast. The second type were amulatados or amembrillados of lighter skin color, when compared with other blacks were indistinguishable in their skin yellow hues.

The slaves were involved in an important economic sectors such as sugar production and mining. Most slaves worked in sugar production and textile mills, which were the two sectors that needed a large, stable workforce, which could not pay enough to attract free laborers to its arduous work. Other sector of slave labor was generally restricted to Mexico City, where they were domestic servants such as maids, coachmen, personal service or armed bodyguards. However, they were more of a status symbol rather than an economic necessity.

Afro-Mexican student of Princeton in USA

The hardship faced by the slaves for their unpaid labour coupled with maltreatment from their masters led to slave rebellions in Mexico and other parts of the Americas, with the first in slave rebellion occurring in Mexican town of Veracruz in 1537. The slaves after rebelling fled and became runaway slaves, commonly referred to as cimarrones. Most of these cimarrones fled to the highlands between Veracruz and Puebla and having received other runaway slaves joining their ranks made their way to the Costa Chica region in what are now Guerrero and Oaxaca. The Runaways in Veracruz formed settlements called “palenques” and started fighting off Spanish authorities. The most famous of these was led by Gaspar Yanga, who fought the Spanish for forty years until the Spanish recognized their autonomy in 1608, making San Lorenzo de los Negros (today Yanga) the first community of free blacks in the Americas. Chronicling the life of africans in the "palenque, in 1591 Spanish Viceroy Don Luis de Velasco reported the existence of a group of cimarrones (Maroons) who had resided for the previous 30 years on a mountain called Coyula who “live as if they were actually in Guinea.

When Yanga and his followers founded their settlement, the population of Mexico City consisted of approximately 36,000 Africans, 116,000 persons of African ancestry, and only 14,000 Europeans.

The source of these figures is the census of 1646 of Mexico City, as reported by Gonzalo Aguirre Beltran in La Poblacion Negra de Mexico (p. 237). These approximate figures include as persons of African ancestry only those designated as Afromestizos, in accordance with the caste-system definitions at the time. The census indicates that there were also more than a million indigenous peoples. In fact, such precise definitions were almost impossible to make, and it is highly probable that the categories Euromestizos and Indomestizos also included persons of African descent. Escaped slaves added to the overwhelming numbers in the cities, establishing communities in Oaxaca as early as 1523.

It must be noted that in the 16th century, the great Spanish Bishop Bartolome de las Casas, the first modern human rights activist, in the sense of battling for justice for another race, persuaded the King of Spain to ban the enslavement of Indians, at least nominally. Yet, bondage for Africans remained legal until "El Negro Guerrero" officially abolished it in 1829.

Having noticed this window of opportunity for the indigenous Indians African men married Native women to ensure that their descendants would be born free. The Africans this so particularly because the African population had a 3 male to 1 female ratio and since children born from Indigenous mothers carried their “free” status. According to the Mexican caste system imposed by Spain, the Indigenous population was considered citizens and could not be made slaves. At the bottom of the caste system were the Black slaves. Escaped slaves resorted to establishing settlements or palenques in Mexico’s inaccessible mountains to preserve their freedom.

Gemelli Careri, in his 1698 visit, concluded, “Mexico City contains about 100,00 inhabitants, but the greatest part of them are Blacks and Mulattoes by reason of the vast number of slaves that has been cessation of the slave trade the enslaved population steadily declined. However, the numbers of free Blacks grew and by 1810 comprised 10 percent of the population or roughly 624,000 people.

During the war of independence 1810- 1821, about 30 to 40 percent of mixed race Mexicans had African in their mix and were more likely to be militant. The Afro-Mestizo was placed between a rock and a hard place—and his inclination toward militancy came from the racist laws limiting jobs, places of residence, and marriage that set Blacks apart. Moreover, slavery was reserved for Africans only, be they mixed or pure. Census data reveal that “from Southern Talisco to Southern Michoacán and through the sugar plantations near Cuautla in Morelos 37% of the population was Afro-Mexican in 1810. The Huasteca uphill region behind the port of Tampico, census data shows the Tampico coast as much as 78 percent Afro Mexican, and in the highlands only 17 percent, the other 83 percent was comprised of Huasteca Indians. West of the Cuautla Valley, 50 percent of the population was Afro Mexican” and it was there that the longest battle of the independence war was fought.

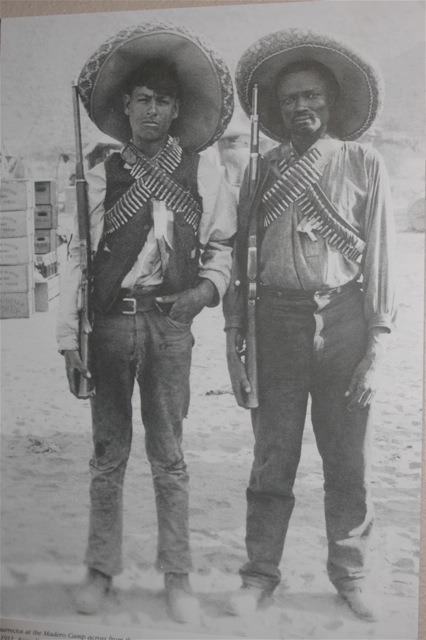

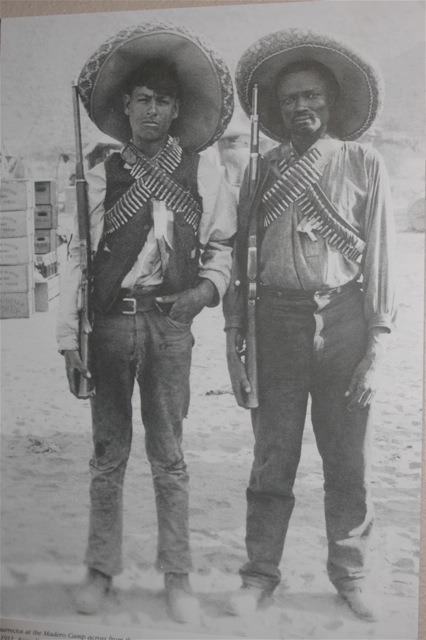

Afro-Mexican soldier and his fellow native Indian soldier

Afro-Mexicans were very important for the war as all historical accounts has revealed. African blood constituted 15% of the Bagio region where Father Miguel Hildago y Castillo launched the freedom fight. The largest guerrilla group in the area was described in 1849 by historian Lucas Alaman as mostly "mulattoes and mestizos" who served under the flamboyant Albino Garcia, who kept guitarists close at hand to play him his favourite "jarabe" songs, the songs of Afro-Mexicans (Fenandez, 1992). Another indication of the importance of the Afro-Mexican during the war of independence is the decree abolishing slavery by priest Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico’s Founding Father, as enticement to attract Afro-Mexicans to the fighting ranks. Likewise, the vital importance of the Afro-Mexican soldier was evident in an incident that took place when Blacks were disgruntled because Jose Maria Morelos, an Afro-mestizo himself and Founding Father of Mexico, refused to recognize General Rayon’s appointment on their behalf. “Disappointed and despondent, they retired to El Veladero and made plans to incite the Negroes in Morelos’s army to slaughter the Whites. When Morelos heard about this activity, he struck hard and fast. Taking a small escort with him, he rushed southward to ‘remove the cancer,’ crushed the revolt before it could be launched, and caught and shot the leaders.”

The Afro-Mestizo was predominant in Morelos’ independence army, which was another reason for targeting, otherwise Morelos would not have viewed this threat as a cancer.

The Mexican war of independence claimed as many as one million lives, many of them Afro-Mexicans. The tragic massacre that took place during Mexico’s war of independence is vividly recounted by one scholar: “The Creole officers, faithful to their gachipin (Spaniard) generals, were willing to massacre the insurgents, and the mestizos and mulattos who formed the rank and file of the army were blindly obedient … when they met the Spaniards in battle, some of them tried to put the Spanish cannon out of action by throwing sombreros over their mouths.”

Abilene (R) and her sisters Diana (L), Maria Esther (2nd L) and Ana Cristina Olmedo pose for a photograph at Punta Maldonado beach in Costa Chica, southern Guerrero state. This region is populated by a majority of AfroMexican people. Photo by heribertorodriguez

When Mexico achieved independence, Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña, one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence and an Afro-Mexican at first collaborated with Agustín de Iturbide, who proposed that the two join forces under what he referred to as the Three Guarantees or El plan de Iguala. This plan gave civil rights to Indians but not to African Mexicans. Guerrero refused to sign the plan unless equal rights were also given to African Mexicans and mulattoes. Clause 12 was then incorporated into the plan. It read: "All inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues."

Iturbide and Guerrero eventually agreed on these ideological mandates – that Mexico be made an independent constitutional monarchy, the abolition of class distinctions between Spaniards, creoles, mestizos and Indians, and that Catholicism be made the state religion – earned Guerrero's support, and, after marching into the capital on 27 September 1821, Iturbide was proclaimed Emperor of Mexico by Congress. However, when Iturbide's policies supported the interests of Mexico's wealthy landowners through continued economic exploitation of the poor and working classes, Guerrero turned against him and came out in favor of a Republic with the Plan of Casa Mata

By 1827 hardly any “Negro” slaves were left in Mexico. The whole slavery issue would have been history were it not for the fact that Texas, in the Northern part of Mexico, was being encroached upon by slave holding Anglos who brought slaves with them to settle unoccupied areas of Texas.

Mexico’s effort to end slavery throughout her territory met with opposition and by the fall of 1825 almost one out of five persons in Texas was a “Negro” slave.

When the general Manuel Gómez Pedraza won the election to succeed Guadalupe Victoria as president, Guerrero, with the aid of general Antonio López de Santa Anna and politician Lorenzo de Zavala, staged a coup d'état and took the presidency on 1 April 1829. Guerrero was elected the second president of Mexico in 1829. As president, Guerrero went on to champion the cause not only of the racially oppressed but also of the economically oppressed. The most notable achievement of Guerrero's short term as president was ordering an immediate abolition of slavery on September 16th of 1829. and emancipation of all slaves. During Guerrero's presidency the Spanish tried to reconquer Mexico, however, the Spanish failed and were defeated at the Battle of Tampico. Stephen Fuller Austin, 1829, in his letter to his sister described Guerrero's Government of Mexico (and Texas) in these words: "This is the most liberal and munificent Government on earth to emigrants – after being here one year you will oppose a change even to Uncle Sam.”

Guerrero was deposed in a rebellion under Vice-President Anastasio Bustamante that began on 4 December 1829. He left the capital to fight the rebels, but was deposed by the Mexico City garrison in his absence on 17 December 1829. Guerrero hoped to come back to power, but General Bustamante captured him from his home through bribery and a group of reactionaries had him executed. After his death, Mexicans loyal to Guerrero revolted, driving Bustamante from his presidency and forcing him to flee for his life. Picaluga, a former friend of Guerrero, who conspired with Bustamante to capture Guerrero, was executed.

Benigno Gallardo, leader in the Guerrero teacher union and Afro-Mexican activist.

Music

To better understand the music’s origins, researcher and expert on Mexican percussive instruments Arturo Chamorro states: "African traces are not present in an obvious manner in traditional Mexican music and those that have such traces are found in levels less obvious. One can argue that through traditional oral music, the panorama of African heritage is much more optimistic than that of strong documents."

Afro-Mexican dance

Even though the African presence in Mexico’s folk music has not been greatly promoted tantamount to that of European and Amerindian populations, there is evidence that music of the Costa Chica region has been impacted by African influence that dates back to slavery. This influence is prevalent in today’s music in the Costa Chica region as well as other states in Mexico. Until the pioneering investigation of Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán in 1946,there was not much research done in regards to the African diaspora and its influence in general and even less in the Costa Chica region. Even though there is supportive evidence of an African past in Mexico’s folk music history,some investigators share contrasting viewpoints. For example, “surprisingly, Vicente Teódulo Mendoza, the most prominent scholar of folk music in Mexico, dedicated minimum attention to the African contribution in traditional music.”

Conversely, other scholars such as Robert Stevenson (1952) and much later Gabriel Moedano (1980) both concur that there is significant African influence in some genres of Mexican music. Within the music of the Costa Chica region, there are specific instruments of African origin that are also particular to the regional sound. Many of these instruments such as the marímbola (finger piano), quijada (jawbone), and tambores de fricción (friction drums) are documented in Chamorro’s Los instrumentos de percusión de México (1984).

A boy plays a donkey's jawbone for the anual Afro-Mexican Dance of the Devils in Cuajinicuilapa community, Guerrero state, Mexico

Instruments: The friction drum (tambor de fricción) isa percussion instrument consisting of a single membrane stretched over an open-ended hollow sound box. The player produces sound by causing the membrane to vibrate by friction. The membrane vibrates by 1) being rubbed with the fingers or with the use of acloth, stick or cord that is attached to its center, or by 2) spinning the drum around a pivot to produce friction. To vary the pitch, the membrane may be depressed with the thumb while playing. The friction drum was primarily used for religious ceremonies and associated with groups descending from the Yoruba and Bantu cultures. The tambor de fricciónis also known as the bote de diabloor tirera in Mexico. As Chamorro states: “Theuse of the friction drum, which is recognized as also having African aspects in its manufacture, appears to have extended itself among various indigenous and mixed communities from the Costa Chica region.”

Afro-Mexican Abraham-Laboriel-Sr “The most widely used session bassist of our time” according to Guitar Player magazine.

Among these communities is the Amuzgo, the Amerindians who called the instrument teconte. Bill Jenkinsconcurs with Chamorro’s statements,that “many friction drums in the New World were of Africa origin.”The marimbais currently a prominent folk instrument in the state of Oaxaca and also apparent in the state of Veracruz(Jenkins). The instrument has been manifested in different parts of the world and is referred to by different names. Marimba, which means “voice of wood,” is a wood or metal instrument whose sound is generated by thin tongues known as lamellae. A derivative of the gyil, the marimba has fourteen wooden keys that are fastened by leather and antelope sinew with calabash gourds beneath the keys. The marimba is not used as a solo instrument, but functions as an accompanying instrument. It also provides the harmonic background in addition to setting the tempo for the band.

From the state of Guerrero, the song “La Llorona,” which features the marimba is a good example of the instrument’s prominence in contemporary music. It also exists in other countries within the African diaspora, such as Guatemala, Peru, Venezuela, and Colombia.

Also in Guerrero, the marímbola (similar to the marimba),is used in a style known as chilena. This genre of music got its name from the immigrants who came to Mexico in search of gold on their way to California. The chilena is also a famous couples’dance with Afro-Hispanic rhythms and Spanish stanzas. It is the product of the African influenced cueca, a folk dance popular in various Hispano-american countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Peru. The marímbola has ties to the balafon in Mali, and the balaphone,balani and balangiin Sierra Leone. Palauk and mahogany wood from Africa gives the instrument its distinct sound. In 1980, a study carried out by André Fara from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH)published findings that established the marimbol[a] as being clearly of African origin as well as being linked to the history of the sanza,which is currently known by its modern name mbira.

The quijada (jaw bone of a donkey, cow or horse) is an instrument that is also called by other names in different countries (e.g.,charrasca in Venezuela, cacharaina in Chile,or quijada quina). The jawbone is weathered until the molars rattle in place. Methodsof playing involve striking the large end of the jawbone with the palm which rattles the teeth, and/or scraping the instrument with a stick.When analyzing the song “Hurra cachucha y los enanos” a song specifically used in the danza de “los diablos,”(the dance of the devil),the use of the quijadais recognized as being dominant. This dance is a celebration that takes place most often during El Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead) in Mexico. In countries where the quijada is known, there tends to be a large population of African descendants. According to the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, among the African influenced instruments of Mexico, the quijada de burrois one of the Mixtec(indigenous Mesoamerican) idiophones with African influence.

Afro-Mexican population in the Costa Chica

The Costa Chica (“small coast” in Spanish) extends from Acapulco to the town of Puerto Ángel in Oaxaca in Mexico’s Pacific coast. The Costa Chica is not well known to travelers, with few attractions, especially where Afro-Mexicans live. Exceptions to this are the beaches of Marquelia and Punta Maldonado in Guerrero and the wildlife reserve in Chacahua, Oaxaca . The area was very isolated from the rest of Mexico, which prompted runaway slaves to find refuge here.

However, this has changed to a large extent with the building of Highway 200 which connects the area to Acapulco and other cities on the Pacific coast. African identity and physical features are stronger here than elsewhere in Mexico as the slaves here did not intermarry to the extent that others did. Not only is black skin and African features more prominent, there are strong examples of African based song, dance and other art forms. Until recently, homes in the area were round mud and thatch huts, the construction of which can be traced back to what are now the Ghana and Ivory Coast. Origin tales often center on slavery.

Afro-Mexican round settlement of African origin at La Coasta Chica, Oaxaca in Mexico

Many relate to a shipwreck (often a slave ship) where the survivors settle here or that they are the descendents of slaves freed for fighting in the Mexican War of Independence. The region has a distinct African-influenced dance called the Danza de los Diablos (Dance of the Devils) which is performed for Day of the Dead. They dance in the streets with wild costumes and masks accompanied by rhythmic music. It is considered to be a syncretism of Mexican Catholic tradition and West African ritual. Traditionally the dance is accompanied by a West African instrument called a bote, but it is dying out as the younger generations have not learned how to play it.

There are a number of “pueblos negros” or black towns in the region such as Corralero and El Ciruelo in Oaxaca, and the largest being Cuajinicuilapa in Guerrero. The latter is home to a museum called the Museo de las Culturas Afromestizos which documents the history and culture of the region.

The Afro-Mexicans here live among mestizos (indigenous/white) and various indigenous groups such as the Amuzgos, Mixtecs, Tlalpanecs and Chatinos . Terms used to denote them vary. White and mestizos in the Costa Chica call them “morenos” (dark-skinned) and the indigenous call them “negros” (black). A survey done in the region determined that the Afro-Mexicans in this region themselves preferred the term “negro,” although some prefer “moreno” and a number still use “mestizo.” Relations between Afro-Mexican and indigenous populations are strained as there is a long history of hostility. Afro-Mexicans are as indigenous to Mexico as the palest Mexican with strictly European ancestry. However, the social stigma and internalized racism associated with blackness and dark skin causes many Afro-Mexicans to feel shame and deny their negritude instead of finding self-acceptance and pride in their dark skin, kinky hair, and African features

afro mexican from costa chica

Afro-Mexican population in Veracruz

Like the Costa Chica, the state of Veracruz has a number of pueblos negros, notably the African named towns of Mandinga, Matamba, Mozambique and Mozomboa as well as Chacalapa, Coyolillo, Yanga and Tamiahua . The town of Mandinga, about forty five minutes south of Veracruz city, is particularly known for the restaurants that line its main street. Coyolillo hosts an annual Carnival with Afro-Caribbean dance and other African elements.

However, tribal and family group were separated and dispersed to a greater extent around the sugar cane growing areas in Veracruz. This had the effect of intermarriage and the loss or absorption of most elements of African culture in a few generations. This intermarriage means that while Veracruz remains “blackest” in Mexico’s popular imagination, those with black skin are mistaken for those from the Caribbean and/or not “truly Mexican". The total population of people of African Descent including people with one or more black ancestors remains very low, at less than 2 percent, the highest of any Mexican state.

Statue of Gaspar Yanga

The phenomena of runaways and slave rebellions began early in Veracruz with many escaping to the mountainous areas in the west of the state, near Orizaba and the Puebla border. Here groups of escaped slaves established defiant communities called “palenques” to resist Spanish authorities. The most important Palenque was established in 1570 by Gaspar Yanga and stood against the Spanish for about forty years until the Spanish were forced to recognize it as a free community in 1609, with the name of San Lorenzo de los Negros. It was renamed Yanga in 1932. Yanga was the first municipality of freed slaves in the Americas. However, the town proper has almost no people of obvious African heritage. These live in the smaller, more rural communities.

Because African descendants dispersed widely into the general population, African and Afro-Cuban influence can be seen in Veracruz’s music dance, improvised poetry, magical practices and especially food. Veracruz son music, best known through the popularity of the hit “La Bamba” has African origins. Veracruz cooking commonly contains Spanish, indigenous and African ingredients and cooking techniques. One defining African influence is the use of peanuts. Even though peanuts are native to the Americas, there is little evidence of their widespread use in the pre Hispanic period. Peanuts were brought to Africa by the Europeans and the Africans adopted them, using them in stews, sauces and many other dishes. The slaves that came later would bring this new cooking with the legume to Mexico. They can be found in regional dishes such as encacahuatado, an alcoholic drink called the torito, candies (especially in Tlacotalpan), salsa macha and even in mole poblano from the neighboring state of Puebla. This influence can be seen as far west as Puebla, where peanuts are an ingredient in mole poblano. Another important ingredient introduced by African cooking is the plantain, which came from Africa via the Canary Islands. In Veracruz, they are heavily used breads, empanadas, desserts, mole, barbacoa and much more. One other defining ingredient in Veracruz cooking is the use of starchy tropical roots, called viandas. They include cassava, malanga, taro and sweet potatoes.

Afro-Mexican population in northern Mexico

There are some towns with few blacks in them, far north of Mexico, especially in Coahuila and the country’s border with Texas. Some ex slaves and free blacks came into northern Mexico in the 19th century from the United States. One particular group was the Mascogos, which consisted of runaway slaves and free blacks from Florida, along with Seminoles and Kickapoos. Many of these settled in and around the town of El Nacimiento, Coahuila, where their descendents remain.

The Afro-Mestizo was predominant in Morelos’ independence army, which was another reason for targeting, otherwise Morelos would not have viewed this threat as a cancer.

The Mexican war of independence claimed as many as one million lives, many of them Afro-Mexicans. The tragic massacre that took place during Mexico’s war of independence is vividly recounted by one scholar: “The Creole officers, faithful to their gachipin (Spaniard) generals, were willing to massacre the insurgents, and the mestizos and mulattos who formed the rank and file of the army were blindly obedient … when they met the Spaniards in battle, some of them tried to put the Spanish cannon out of action by throwing sombreros over their mouths.”

Abilene (R) and her sisters Diana (L), Maria Esther (2nd L) and Ana Cristina Olmedo pose for a photograph at Punta Maldonado beach in Costa Chica, southern Guerrero state. This region is populated by a majority of AfroMexican people. Photo by heribertorodriguez

When Mexico achieved independence, Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña, one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence and an Afro-Mexican at first collaborated with Agustín de Iturbide, who proposed that the two join forces under what he referred to as the Three Guarantees or El plan de Iguala. This plan gave civil rights to Indians but not to African Mexicans. Guerrero refused to sign the plan unless equal rights were also given to African Mexicans and mulattoes. Clause 12 was then incorporated into the plan. It read: "All inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues."

Iturbide and Guerrero eventually agreed on these ideological mandates – that Mexico be made an independent constitutional monarchy, the abolition of class distinctions between Spaniards, creoles, mestizos and Indians, and that Catholicism be made the state religion – earned Guerrero's support, and, after marching into the capital on 27 September 1821, Iturbide was proclaimed Emperor of Mexico by Congress. However, when Iturbide's policies supported the interests of Mexico's wealthy landowners through continued economic exploitation of the poor and working classes, Guerrero turned against him and came out in favor of a Republic with the Plan of Casa Mata

By 1827 hardly any “Negro” slaves were left in Mexico. The whole slavery issue would have been history were it not for the fact that Texas, in the Northern part of Mexico, was being encroached upon by slave holding Anglos who brought slaves with them to settle unoccupied areas of Texas.

Mexico’s effort to end slavery throughout her territory met with opposition and by the fall of 1825 almost one out of five persons in Texas was a “Negro” slave.

Portrait of Young Mario Marcel Salas an Afro-Mexican who became American civil rights leader, author and politician

When the general Manuel Gómez Pedraza won the election to succeed Guadalupe Victoria as president, Guerrero, with the aid of general Antonio López de Santa Anna and politician Lorenzo de Zavala, staged a coup d'état and took the presidency on 1 April 1829. Guerrero was elected the second president of Mexico in 1829. As president, Guerrero went on to champion the cause not only of the racially oppressed but also of the economically oppressed. The most notable achievement of Guerrero's short term as president was ordering an immediate abolition of slavery on September 16th of 1829. and emancipation of all slaves. During Guerrero's presidency the Spanish tried to reconquer Mexico, however, the Spanish failed and were defeated at the Battle of Tampico. Stephen Fuller Austin, 1829, in his letter to his sister described Guerrero's Government of Mexico (and Texas) in these words: "This is the most liberal and munificent Government on earth to emigrants – after being here one year you will oppose a change even to Uncle Sam.”

Guerrero was deposed in a rebellion under Vice-President Anastasio Bustamante that began on 4 December 1829. He left the capital to fight the rebels, but was deposed by the Mexico City garrison in his absence on 17 December 1829. Guerrero hoped to come back to power, but General Bustamante captured him from his home through bribery and a group of reactionaries had him executed. After his death, Mexicans loyal to Guerrero revolted, driving Bustamante from his presidency and forcing him to flee for his life. Picaluga, a former friend of Guerrero, who conspired with Bustamante to capture Guerrero, was executed.

Benigno Gallardo, leader in the Guerrero teacher union and Afro-Mexican activist.

Music

To better understand the music’s origins, researcher and expert on Mexican percussive instruments Arturo Chamorro states: "African traces are not present in an obvious manner in traditional Mexican music and those that have such traces are found in levels less obvious. One can argue that through traditional oral music, the panorama of African heritage is much more optimistic than that of strong documents."

Afro-Mexican dance

Even though the African presence in Mexico’s folk music has not been greatly promoted tantamount to that of European and Amerindian populations, there is evidence that music of the Costa Chica region has been impacted by African influence that dates back to slavery. This influence is prevalent in today’s music in the Costa Chica region as well as other states in Mexico. Until the pioneering investigation of Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán in 1946,there was not much research done in regards to the African diaspora and its influence in general and even less in the Costa Chica region. Even though there is supportive evidence of an African past in Mexico’s folk music history,some investigators share contrasting viewpoints. For example, “surprisingly, Vicente Teódulo Mendoza, the most prominent scholar of folk music in Mexico, dedicated minimum attention to the African contribution in traditional music.”

Conversely, other scholars such as Robert Stevenson (1952) and much later Gabriel Moedano (1980) both concur that there is significant African influence in some genres of Mexican music. Within the music of the Costa Chica region, there are specific instruments of African origin that are also particular to the regional sound. Many of these instruments such as the marímbola (finger piano), quijada (jawbone), and tambores de fricción (friction drums) are documented in Chamorro’s Los instrumentos de percusión de México (1984).

A boy plays a donkey's jawbone for the anual Afro-Mexican Dance of the Devils in Cuajinicuilapa community, Guerrero state, Mexico

Instruments: The friction drum (tambor de fricción) isa percussion instrument consisting of a single membrane stretched over an open-ended hollow sound box. The player produces sound by causing the membrane to vibrate by friction. The membrane vibrates by 1) being rubbed with the fingers or with the use of acloth, stick or cord that is attached to its center, or by 2) spinning the drum around a pivot to produce friction. To vary the pitch, the membrane may be depressed with the thumb while playing. The friction drum was primarily used for religious ceremonies and associated with groups descending from the Yoruba and Bantu cultures. The tambor de fricciónis also known as the bote de diabloor tirera in Mexico. As Chamorro states: “Theuse of the friction drum, which is recognized as also having African aspects in its manufacture, appears to have extended itself among various indigenous and mixed communities from the Costa Chica region.”

Afro-Mexican Abraham-Laboriel-Sr “The most widely used session bassist of our time” according to Guitar Player magazine.

Among these communities is the Amuzgo, the Amerindians who called the instrument teconte. Bill Jenkinsconcurs with Chamorro’s statements,that “many friction drums in the New World were of Africa origin.”The marimbais currently a prominent folk instrument in the state of Oaxaca and also apparent in the state of Veracruz(Jenkins). The instrument has been manifested in different parts of the world and is referred to by different names. Marimba, which means “voice of wood,” is a wood or metal instrument whose sound is generated by thin tongues known as lamellae. A derivative of the gyil, the marimba has fourteen wooden keys that are fastened by leather and antelope sinew with calabash gourds beneath the keys. The marimba is not used as a solo instrument, but functions as an accompanying instrument. It also provides the harmonic background in addition to setting the tempo for the band.

Toña la Negra (born Maria Antonia del Carmen Peregrino Álvarez, Veracruz 17 October 1912– Mexico City, 19 December 1982) was an Afro-Mexican singer known for her interpretation of boleros, sones, rumbas and songs from Agustín Lara. She first became famous by her interpretation of Lara's song "Enamorada", he also wrote "Lamento Jarocho" specially for her to sing. She also sang for the famous Sonora Matancera, recording two numbers in the studio with this musical institution. The alley where she was born in the old barrio of "La Huaca" in the city of Veracruz, México, carries her name. After her death the municipality of Veracruz has erected a statue of Toña la Negra within sight of the old church of Cristo del Buen Viaje (1609) bordering on the La Huaca barrio.

From the state of Guerrero, the song “La Llorona,” which features the marimba is a good example of the instrument’s prominence in contemporary music. It also exists in other countries within the African diaspora, such as Guatemala, Peru, Venezuela, and Colombia.

Afro-Mexican dance of the devil costume

Also in Guerrero, the marímbola (similar to the marimba),is used in a style known as chilena. This genre of music got its name from the immigrants who came to Mexico in search of gold on their way to California. The chilena is also a famous couples’dance with Afro-Hispanic rhythms and Spanish stanzas. It is the product of the African influenced cueca, a folk dance popular in various Hispano-american countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Peru. The marímbola has ties to the balafon in Mali, and the balaphone,balani and balangiin Sierra Leone. Palauk and mahogany wood from Africa gives the instrument its distinct sound. In 1980, a study carried out by André Fara from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH)published findings that established the marimbol[a] as being clearly of African origin as well as being linked to the history of the sanza,which is currently known by its modern name mbira.

The quijada (jaw bone of a donkey, cow or horse) is an instrument that is also called by other names in different countries (e.g.,charrasca in Venezuela, cacharaina in Chile,or quijada quina). The jawbone is weathered until the molars rattle in place. Methodsof playing involve striking the large end of the jawbone with the palm which rattles the teeth, and/or scraping the instrument with a stick.When analyzing the song “Hurra cachucha y los enanos” a song specifically used in the danza de “los diablos,”(the dance of the devil),the use of the quijadais recognized as being dominant. This dance is a celebration that takes place most often during El Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead) in Mexico. In countries where the quijada is known, there tends to be a large population of African descendants. According to the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, among the African influenced instruments of Mexico, the quijada de burrois one of the Mixtec(indigenous Mesoamerican) idiophones with African influence.

Afro-Mexican population in the Costa Chica

The Costa Chica (“small coast” in Spanish) extends from Acapulco to the town of Puerto Ángel in Oaxaca in Mexico’s Pacific coast. The Costa Chica is not well known to travelers, with few attractions, especially where Afro-Mexicans live. Exceptions to this are the beaches of Marquelia and Punta Maldonado in Guerrero and the wildlife reserve in Chacahua, Oaxaca . The area was very isolated from the rest of Mexico, which prompted runaway slaves to find refuge here.

However, this has changed to a large extent with the building of Highway 200 which connects the area to Acapulco and other cities on the Pacific coast. African identity and physical features are stronger here than elsewhere in Mexico as the slaves here did not intermarry to the extent that others did. Not only is black skin and African features more prominent, there are strong examples of African based song, dance and other art forms. Until recently, homes in the area were round mud and thatch huts, the construction of which can be traced back to what are now the Ghana and Ivory Coast. Origin tales often center on slavery.

Afro-Mexican round settlement of African origin at La Coasta Chica, Oaxaca in Mexico

Many relate to a shipwreck (often a slave ship) where the survivors settle here or that they are the descendents of slaves freed for fighting in the Mexican War of Independence. The region has a distinct African-influenced dance called the Danza de los Diablos (Dance of the Devils) which is performed for Day of the Dead. They dance in the streets with wild costumes and masks accompanied by rhythmic music. It is considered to be a syncretism of Mexican Catholic tradition and West African ritual. Traditionally the dance is accompanied by a West African instrument called a bote, but it is dying out as the younger generations have not learned how to play it.

There are a number of “pueblos negros” or black towns in the region such as Corralero and El Ciruelo in Oaxaca, and the largest being Cuajinicuilapa in Guerrero. The latter is home to a museum called the Museo de las Culturas Afromestizos which documents the history and culture of the region.

The Afro-Mexicans here live among mestizos (indigenous/white) and various indigenous groups such as the Amuzgos, Mixtecs, Tlalpanecs and Chatinos . Terms used to denote them vary. White and mestizos in the Costa Chica call them “morenos” (dark-skinned) and the indigenous call them “negros” (black). A survey done in the region determined that the Afro-Mexicans in this region themselves preferred the term “negro,” although some prefer “moreno” and a number still use “mestizo.” Relations between Afro-Mexican and indigenous populations are strained as there is a long history of hostility. Afro-Mexicans are as indigenous to Mexico as the palest Mexican with strictly European ancestry. However, the social stigma and internalized racism associated with blackness and dark skin causes many Afro-Mexicans to feel shame and deny their negritude instead of finding self-acceptance and pride in their dark skin, kinky hair, and African features

afro mexican from costa chica

Afro-Mexican population in Veracruz

Like the Costa Chica, the state of Veracruz has a number of pueblos negros, notably the African named towns of Mandinga, Matamba, Mozambique and Mozomboa as well as Chacalapa, Coyolillo, Yanga and Tamiahua . The town of Mandinga, about forty five minutes south of Veracruz city, is particularly known for the restaurants that line its main street. Coyolillo hosts an annual Carnival with Afro-Caribbean dance and other African elements.

However, tribal and family group were separated and dispersed to a greater extent around the sugar cane growing areas in Veracruz. This had the effect of intermarriage and the loss or absorption of most elements of African culture in a few generations. This intermarriage means that while Veracruz remains “blackest” in Mexico’s popular imagination, those with black skin are mistaken for those from the Caribbean and/or not “truly Mexican". The total population of people of African Descent including people with one or more black ancestors remains very low, at less than 2 percent, the highest of any Mexican state.

Statue of Gaspar Yanga

The phenomena of runaways and slave rebellions began early in Veracruz with many escaping to the mountainous areas in the west of the state, near Orizaba and the Puebla border. Here groups of escaped slaves established defiant communities called “palenques” to resist Spanish authorities. The most important Palenque was established in 1570 by Gaspar Yanga and stood against the Spanish for about forty years until the Spanish were forced to recognize it as a free community in 1609, with the name of San Lorenzo de los Negros. It was renamed Yanga in 1932. Yanga was the first municipality of freed slaves in the Americas. However, the town proper has almost no people of obvious African heritage. These live in the smaller, more rural communities.

Afro-Mexican lady

Afro-Mexican

Afro-Mexican population in northern Mexico

There are some towns with few blacks in them, far north of Mexico, especially in Coahuila and the country’s border with Texas. Some ex slaves and free blacks came into northern Mexico in the 19th century from the United States. One particular group was the Mascogos, which consisted of runaway slaves and free blacks from Florida, along with Seminoles and Kickapoos. Many of these settled in and around the town of El Nacimiento, Coahuila, where their descendents remain.

Ray Dalton - Afro-Mexican American singer-songwriter. His mother is an Afro-Mexican

Africa’s Lost Tribe In Mexico

NEW AFRICAN MAGAZINE

1 OCTOBER 2012

"The existence of Afro-Mexicans was officially affirmed in the 1990s when the Mexican government acknowledged Africa as Mexico’s “third root”. But Mexico’s real history shows the African presence in the country going back thousands of years. Despite the official recognition of the contribution of Africa and Afro-Mexicans to Mexican society throughout the ages, the plight of African-descended people in Mexico is still desperate, reports Miriam Jimenez Roman. (Additional reporting by Tom Mbakwe)"

Last year, a bilingual exhibition, The African Presence in México: Yanga to the Present, was mounted by the Oakland Museum and the DuSable Museum on both sides of the Mexican border – in the US and Mexico itself. It traced how Africans – fewer than 2% of colonial Mexico’s (1521-1810) population – significantly enriched Mexican culture through their art, music, language, cuisine, and dance. The African Presence in México invited Mexican-Americans and African-Americans to look at their identities in light of their shared histories in Mexico and the United States.

The Spanish first brought Africans to Mexico in 1519 to work in the agrarian and silver industries, under often brutal conditions. There were constant slave protests and runaways (cimarrónes) who established settlements in the mountains of Orizaba. In January 1609, Gasper Yanga, a runaway slave elder, led the cimarrónes (or maroons) to a successful resistance against a special army sent by the Spanish Crown to crush their uprising. After several cimarrón victories, the Spanish acquiesced to the slaves’ demand for land and freedom. Yanga founded the first free African township in the Americas, San Lorenzo de los Negros, near Veracruz. It was renamed in his honour in the 1930s.

Slavery in Mexico was abolished in 1810 by Jose María Morelos y Pavón, leader of the Mexican War of Independence. As a mulatto (Spanish and African), Morelos was directly affected by Mexico’s prejudices. Racial mixes were seen as undesirable by a society that aspired to purity of race and blood (ie, Spanish only).

In 1992, as part of the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the Spanish in the Americas, the Mexican government officially acknowledged that African culture in the country represented la tercera raiz (the third root) of Mexican culture, with the Spanish and indigenous peoples. But the plight of Afro-Mexicans has not improved much since the recognition of 1992.

As Alexis Okeowo, a black journalist in the Mexican capital, Mexico City, attests, when she visited Yanga, her heart broke. “As I arrived in town,” she reported, “I peered out of my taxi window at the pastel-painted storefronts and the brown-skinned residents walking along the wide streets. ‘Where are the black Mexicans?’ I wondered. A central sign proclaimed Yanga’s role as the first Mexican town to be free from slavery, yet the descendants of these former slaves were nowhere to be found. I would later learn that most live in dilapidated settlements outside of town.”

The next morning when she went searching for the Afro-Mexicans, Okeowo found that though she had grown used to the rarity of black people in Mexico City, it was different at Yanga, where she was not only stared at but also pointed at.

“The stares were cold and unfriendly, and especially unnerving in a town named for an African revolutionary,” Okeowo recalled. “ ‘Mira, una negra,’ I heard people whisper to one another. ‘Look, a black woman.’ ‘Negra! Negra!’, taunted an old man with a shock of white hair under a tan sombrero.

“Surrounded by a group of men, [the old man] gazed at me with a big, toothy grin. He seemed to be waiting for me to come over and talk to him. Shocked, I shot him a dirty look and headed into [a] library’s courtyard.”

Okeowo continued: “The notion of race in Mexico is frustratingly complex. This is a country where many are proud to claim African blood, yet discriminate against their darker countrymen. Black Mexicans complain that such bigotry makes it especially hard for them to find work. Still, I was surprised to feel like such an alien intruder in a town where I had hoped to feel something like familiarity. Afro-Mexicans are among the poorest in the nation. Many are shunted to remote shantytowns, well out of reach of basic public services, such as schools and hospitals.

“Activists for Afro-Mexicans face an uphill battle for government recognition and economic development. They have long petitioned to be counted in Mexico’s national census, alongside the country’s 56 other official ethnic groups, but to little avail. Unofficial records put their number at one million.”

In response to activist pressure, Okeowo said, Mexico’s government released a study at the end of 2008 that confirmed that Afro-Mexicans suffered from institutional racism. “Employers are less likely to employ blacks, and some schools prohibit access based on skin colour. But little has been done to change this. Afro-Mexicans lack a powerful spokesperson, so they continue to go unnoticed by the country’s leadership.”

Rodolfo Prudente Dominguez, an Afro-Mexican activist, told Okeowo that all they wanted was recognition of their basic rights and respect of their dignity. “There should be sanctions against security and immigration agents who detain us, because they deny our existence on our own land,” said Dominguez.

Okeowo continued: “If you have not heard of Mexico’s native blacks, you are not alone. The story that has been passed down through generations is that their ancestors arrived on a slave boat filled with Cubans and Haitians, which sank off Mexico’s Pacific coast. The survivors hid away in fishing villages on the shore. The story is a myth: Spanish colonialists trafficked African slaves into ports on the opposite Gulf coast, and slaves were distributed further inland. The persistence of this story explains the reluctance of many black Mexicans to embrace the label ‘Afro’, and why many Mexicans assume black nationals hail from the Caribbean.

Beautiful Afro-Mexican lady

“Colonial records show that around 200,000 African slaves were imported into Mexico in the 16th and 17th centuries to work in silver mines, sugar plantations, and cattle ranches. But after Mexico won its independence from Spain, the needs of these black Mexicans were ignored. Some Afro-Mexican activists identify themselves as part of the African diaspora. Given their rejection from Mexican culture, this offers a more empowering cultural reference,” Okeowo reported, adding:

“In a place where everyone is considered ‘mixed race’, owing to the country’s long colonial history, skin colour is clearly a symbol of status. Many Mexicans are generous and kind to me, viewing my otherness as interesting and lovely. Yet black Mexicans are often mistreated and ostracised. I think about this unsettling tension when I occasionally pass a black Mexican in Mexico City, and she gives me a slight, genuine smile.”

Okeowo’s report has been confirmed by other writers such as Bobby Vaughn, an African-American whose interest in Afro-Mexicans has made him an expert on the subject. On his website, he compares census figures from colonial Mexico dating from 1570 to 1742, and shows that in 1570 while there were 6,644 Europeans in Mexico, there were as many as 20,569 Africans there, while native Mexicans were in the region of 3,366,860. By 1646, these figures had rocketed to 13,780 Europeans and 35,089 Africans, but the native population had decreased to 1,269,607. At the same time, the population of Africans of mixed race (Afro-Mestizos) had increased to 116,529 (from only 2,437 in 1570), while Europeans of mixed race had shot up to 168,568 (from 11,067 in 1570).

In 1742, however, the African population had decreased to 20,131 while the European figure had slightly come down to 9,814. But there had been a huge jump in the Afro-Mestizos population to 266,196 while the Euro-Mestizos had increased to 391,512.

“The numerical significance of these figures,” writes Bobby Vaughn, “becomes clear when we compare the African and Afro-Mestizo (mixed population) to the Spanish population. In the early colonial period, European immigration was extremely small – and for good reason. There were great risks and many uncertainties in the Americas. Few families were willing to immigrate until some assurance of stability was demonstrated. Therefore, very few European women immigrated, thus preventing the natural growth of the Spanish population. The point that must be made here is the fact that the black population in the early colony was by far higher than that of the Spanish. In 1570, we see that the black population is about three times that of the Spanish. In 1646, it is about 2.5 times as large, and in 1742 blacks still outnumber the Spanish. It is not until 1810 that Spaniards are more numerous.”

According to Vaughn, Mexico’s Costa Chica Region is one of two regions in the country with significant black populations today. The other is the State of Veracruz on the Gulf Coast. He, too, confirms that racism is still rife and there is little social interaction between Mexico’s black people and the indigenous people.

“Part of this is the issue of the language barrier, but I believe the issue is more complex than that,” Vaughn reports. “There has been a long history of hostility between the two groups, and while today there is no open hostility, negative stereotypes abound on both sides.”

In April 2008, the Los Angeles Times published an article confirming Vaughn’s views. “In Mexico, the story of the country’s black population has been largely ignored in favour of an ideology that declares that all Mexicans are ‘mixed race’. But it’s the mixture of indigenous and European heritage that most Mexicans embrace; the African legacy is overlooked,” said the article, written by the paper’s staff writer John L. Mitchell. Michell quoted Padre Glyn Jemmott, a Roman Catholic priest from Trinidad and Tobago who had been stationed in Mexico since 1984, as telling him: “They are saying we are all the same and therefore there is no reason to distinguish yourself. What they are not saying is that in ordinary life in Mexico, lighter-skinned Mexicans are accepted and have first place.”

The exhibition

The bilingual exhibition by the Oakland Museum featured paintings, prints, movie posters, photographs, sculpture, costumes, masks, and musical instruments associated with Mexico’s la tercera raiz. It was a fascinating hybrid – a visual arts exhibition based on a cultural history. A similar exhibition, by the same name, was mounted by DuSable Museum, curated by Sangrario Cruz of the University of Veracruz, and Cesareo Moreno, the visual arts director of the National Museum of Mexican Art. This exhibition also used paintings, photographs, lithographs and historical texts to highlight the impact the Africans had on Mexican culture.

The exhibition examined the complexity of race, culture, politics, and social stratification. No exhibition had showcased the history, artistic expressions and practices of Afro-Mexicans in such a broad scope as this one, which included a comprehensive range of artwork from 18th century colonial caste paintings to contemporary artistic expressions. Organised and originally presented by the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, this travelling exhibition made stops in New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington DC and California, as well as Monterrey and Veracruz, Mexico.

The exhibition featured important historical figures, such as Yanga, and illuminates the contributions of Africans to the artistic, culinary, musical and cultural traditions of Mexican culture from the past through the present day. Also featured were Afro-Mexican artists such as Ignacio Canela, Mario Guzman, Guillermo Vargas, Hermengildo Gonzalez; and other artists such as Rufino Tamayo, Elizabeth Catlett, Francisco Toledo, Maria Yampolski and Francisco Mora.

One of the star features of the exhibition was the stunning photographs by Tony Gleaton of the black people of Mexico. Gleaton is an Afro-Mexican himself, and the looks of amazement and disbelief on the faces of first-time viewers of his photographs were eloquent testimony to the significance of the images. Particularly to those who had little or no knowledge about societies beyond the borders of the United States, these photographs were a revelation. The photos forced them to rethink many of their preconceptions not only about Mexico as a country but more generally about issues such as race, ethnicity, culture and national identity.

On a hot and humid July day last year, I rode with friends to the town of Yanga, which has received in recent years considerable attention as one of the Americas’ earliest settlements founded by fugitive slaves.

Today, a recently erected statue of the town’s founder – originally a rebellious Muslim man from what is now Nigeria –stands on the outskirts, more a testimony to the persistence of a few Mexican anthropologists who “re-discovered” the place than to the historical memory of its founder’s descendants.

The story of Yanga

As I strolled through the area and talked to the residents, and saw the evidence of an African past in their faces, I discovered that they had little more than amused curiosity about outsiders who express interest in their past. Yanga’s people have quite simply been living their lives as they always have, making the adjustments necessary in a changing world and giving little thought to an aspect of their history for which they are now being celebrated.

The story of Yanga and his followers is remarkable for being so typical: the town’s relative isolation is the reason for its founding and for its continued existence as a predominately black enclave. Fugitive slave communities were commonly established in difficult-to-reach areas in order to secure their inhabitants from recapture. But their physical isolation has also led to their being ignored. Particularly since Mexico’s Revolution (1910-29), the Yangas of Mexico – mostly found dispersed throughout the states of Veracruz, Oaxaca and Guerrero (south of Acapulco) – have been out of sight and out of mind, generally considered unworthy of any special attention.

Mexico’s African presence has been relegated to an obscured slave past, pushed aside in the interest of a national identity based on a mixture of indigenous and European cultural mestizaje.

In practice, this ideology of “racial democracy” favours the European presence; too often the nation’s glorious indigenous past is reduced to folklore and ceremonial showcasing. But the handling of the African “third root” is even more dismissive.

There are notable exceptions to this lack of attention. The anthropologist, Gonzalo Aguirre Beltran’s seminal works (La Problema Negra de Mexico, 1519-1810 (Mexico’s Negro Problem) published in 1946; and Cuijla: Esbozo Etnografico de un Pueblo Negro, published in 1989 by the Universidad Veracruzana) remain among the most important on the subject.

Doubtless influenced by the interest in Africans and their descendants in other parts of the world, a small but significant group of Mexican intellectuals began, during the past decade, to focus on black Mexicans.

It is true that the State of Veracruz (and especially the port city of the same name) is generally recognised as having “black”

people. In fact, there is a widespread tendency to identify all Mexicans who have distinctively “black” features as coming from Veracruz.

In addition to its relatively well-known history as a major slave port, Veracruz received significant numbers of descendants of Africa from Haiti and Cuba during the latter 19th and early 20th centuries.

But, for all intents and purposes, the biological, cultural and material contributions of the more than 200,000 Africans and their descendants to the formation of Mexican society do not figure in the equation at all. It is impossible to arrive at precise figures on the volume of enslaved Africans brought to Mexico or the rest of the Americas because, hungry for slaves and eager to avoid payment of duties, traders and buyers often resorted to smuggling. The 200,000 figure is generally recognised as a conservative estimate.