Kamba women from Kenya. courtesy singingwells.org

The Kamba with the total population of over 4,466,000 people is regarded as Kenya`s fifth largest ethnic group. Apart from Kenya, Kamba people can also be found in Uganda, Tanzania and in south American country of Paraguay. The population of Akamba in Kenya is over 4, 348,000, about about 8,280 in Uganda and 110,000 in Tanzania.

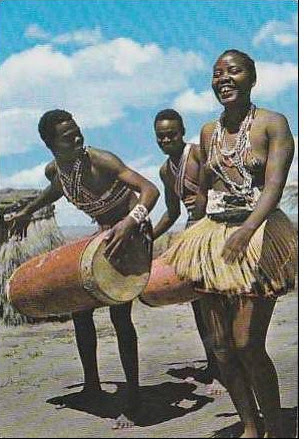

Undoubtedly the most spectacular manifestation of traditional Kamba culture was their dancing, performed to throbbing polyrhythmic drum beats. It was characterised by exceptionally acrobatic leaps and somersaults, which flung dancers into the air. The style of playing was similar to that of the equally disappeared traditions of the Embu and Chuka: the drummers would hold the long drums between their legs, and would also dance. (Just click here http://www.singingwells.org/stories/day-1-nairobi-to-kiongwe-to-muranga/) and also watch their videos here: http://www.singingwells.org/stories/day-1-nairobi-to-kiongwe-to-muranga/

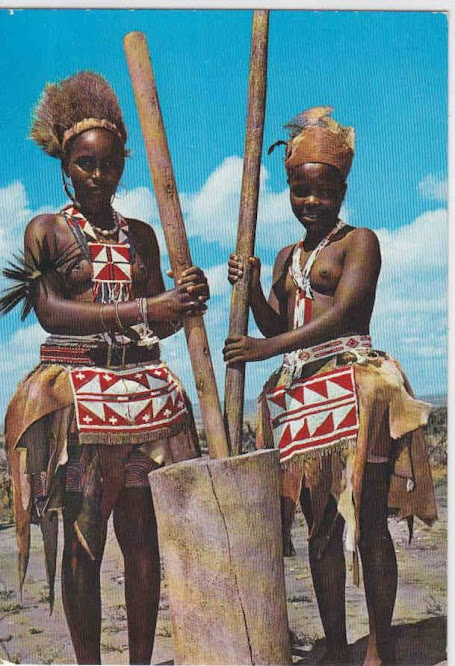

Kamba women in their native dress

Interestingly, Kamba people as music and dance loving people are the original African descendants that founded the city of Kamba Cuá, an important Central Department Afro Paraguayan community in Paraguay. Kamba Cue people of Paraguay are known famously in South America for their awesome, intense and lively traditional African drumming and dancing performances. The Akamba are known in Paraguay as Artigas Cue -or "black of Kamba Cuá". They arrived in Paraguay as members of a regiment of 250 spearmen, men and women, who accompanied General Jose Gervasio Artigas, the independence revolutionary leader of the Eastern Band (the current Uruguay) in his exile in Paraguay in 1820.

Ethnic African Kamba people of Kamba Cue in Paraguay performing their traditional dance

After their arrival to Asunción, they settled in the Campamento Loma area, practicing dairy and secondarily agriculture. However, in the 1940s, they were dispossessed of their land by General Higinio Morinigo. Out of their land of 100 hectares they were given paltry 3 hectares to stay on. However, the community survived, kept his chapel and dances, created a football club ("Jan Six-ro") and one school of drum and dance for children. Their ballet is the only Afro-Paraguayan expression, and premiered at the Folk Festival peach "Uruguay Yi sings in" 1992, where it won the "Golden charrúa". Their original lands at Campamento Loma remained vacant, and Kamba Cuá recently occupied them and planted the manioc, but by unfair and discriminating government decision (post-Stroessner), they were accused of being "terrorists", beaten and evicted.

Ethnic African Kamba people of Kamba Cue in Paraguay performing their traditional dance

Today, according official estimates, in Kumba Cuá there live about 300 families (between 1.200 and 2,500 people). However, according censuses of the Afro Paraguayan Association Kamba Cuá, this community it formed has only 422 people.

Historically, Kamba were ancient hunters that traveled together with their Bantu cousins, the Kikuyus, in the Great Bantu migration from West Africa to Central, Eastern and Southern Africa. It is believed that Kamba and the Kikuyus came to settle together in Kenya as one group until they separated. Kamba settled in Taveta until the 17th century when they dispersed to the lower parts of the Eastern province. The major reason for migration was their search of water and pasture for their livestock.

Despite the incontrovertible evidence that Kamba are undiluted Bantu group, some anthropologists believe that the Akamba as a result of living amongst various Kenyan ethnic groups, are now a mixture of several East African people, and bear traits of the Bantu farmers (Kikuyu, Taita) as well as those of the Nilotic pastoralists (Maasai, Kalenjin, Borana, etc.) and the cushite communities with whom they share borders, to the east of Tsavo.

Kamba women from Kiongwe village in Kenya

During the colonial era, British colonial officials considered the Kamba to be the premier martial

race of Africa. The Kamba themselves appeared to embrace this label by enlisting in the colonial army in large numbers. After confidently describing the Kamba serving in the King's African Rifles (the KAR, Britain's East African colonial army) as loyal "soldiers of the Queen" during the Mau Mau Emergency, a press release by the East Africa Command went on to characterize the Kamba as a "fighting race." These sentiments were echoed by other colonial observers in the early 1950s who deemed the Kamba a hardy, virile, courageous, and "mechanically-minded tribe." Considered by many officers to be the "best [soldierly] material in Africa," the Kamba supplied the KAR with askaris (soldiers) at a rate that was three to four times their percentage of the overall Kenyan population.'(http://www.artsci.wustl.edu/~tparsons/journal_articles/kamba.pdf)

The Kamba people were also very brave and successfully resisted an attempt by the British colonialist to seize their livestock in an obnoxious livestock control legislation in 1938. They peacefully fought the British until the law was repealed.

Among the Akamba people, lack of rain is considered an event requiring ritual intervention. As a result they perform a ritual rain making dance called Kilumi. It is a healing rite designed to restore environmental balance through spiritual blessings, movement, offering, and prayers. According to Akamba, Kilumi has been present since the very beginning of Kamba existence. This ritual emphasizes symbolic dance movements as a key force in achieving the goal of the ceremony. The heart of the dance ritual is its spiritual essence; in fact, it is the spiritual aspect that distinguishes the dances of Africans and their descendants worldwide. For this reason, it is important to understand the nature of rituals. Dance rituals take participants on a journey; they are designed to foster a transformation moving them to different states, with the ultimate goal of invoking spiritual intervention to resolve the problem at hand.

Akamba women with their basket

In line with other collective cultures, identity is based on the social system; therefore it is not strange to find among the Kamba community‟s source of intellectual property proverbs such as, Kathoka kanini kaitemaa muti munene, Which roughly translates to (A small axe does not chop down a huge tree), or another one too is; Kyaa kimwe kiyuwaa ndaa, (One finger cannot squash a bug) to emphasize how peoples‟ allegiance to groups takes priority over their personal goals.

Kamba people of Kenya

A famous Kamba woman called Syokimau, a Prophetess and a great Healer - Prophesied the coming of the white people to Kenya and prophesied also about the construction of the Mombasa to Kisumu railway line. In her prophecy she said she could see people of a different colour carrying fire inside waters which was later to be understood as white people in vessels carrying match boxes and guns. She prophesied seeing a long snake that whose head was in the Indian Ocean and the tail was in Lake Victoria.

Dr Willy Mutunga, the current Chief Justice of Kenya is an ethnic Kamba man

Kitili Maluki Mwendwa, the first black Chief Justice of independent Kenya, Dr Willy Mutunga, current Chief Justice of Kenya, Samuel Kivuitu chairman of Electoral Commission, Professor Kivutha Kibwana, former cabinet minister, former Dean of Law Faculty University Of Nairobi and current Governor Makueni are all notably people from Kamba tribe.

Kitili Maluki Mwendwa, the youngest and first black Chief Justice of independent Kenya was from Kamba tribe.

Mythology (Creation Story)

Like all other Bantu, communities, the Akamba have a story of origin that differs greatly from that of the Kikuyu. It goes like:

"In the beginning, Mulungu created a man and a woman. This was the couple from heaven and he proceeded to place them on a rock at Nzaui where their foot prints, including those of their livestock can be seen to this day.

Mulungu then caused a great rainfall. From the many anthills around, a a man and a woman came ou. These were the initiators of the ‘spirits clan’- the Aimo. It so happened that the couple from heaven had only sons while the couple from the anthill had only daughters. Naturally, the couple from heaven paid dowry for the daughters of the couple from the anthill. The family and their cattle greatly increased in numbers. With this prosperity, they forgot to give thanks to their creator. Molungu punished them with a great famine. This lead dispersal as the family scattered in search of food. Some became the Kikuyu, others the Meru while some remained as the original people, the Akamba."

The Akamba are not specific about the number of children that each couple had initially.

Iconic Tennis legend, Serena Williams dances with traditional dancers from the Kamba tribe. (AFP)

Language

The Kamba people speak Kikamba or Kekamba language which is a Bantu language belonging to the larger Niger-Congo language phylum. It is currently spoken by over 6 million people. In Kenya, Kamba is generally spoken in four (4) out of the forty-seven (47) Counties of Kenya. These counties are Machakos, Kitui and Makueni. The Machakos variety is considered the standard variety of the three dialects and has been used in the translation of the Bible and in basic level education.

Kamba tribe man and iconic Kenyan musician and richest artist, Ken wa Maria dancing

About 5000 people speak Kikemba or (Thaisu) in Tanzania`s Tanga Region, Muheza district, east Usambara mountains north base, Bwiti and Magati villages.

The Kamba language has lexical similarities to other Bantu languages such as Kikuyu, Meru, and Embu.

Its dialects are Masaku, Mumoni, North Kitui, South Kitui. Lexical similarity: 67% with Gikuyu [kik], 66% with Embu [ebu], 63% with Chuka [cuh], 57%–59% with Kimîîru [mer].

Tanga Region, Muheza district, east Usambara mountains north base, Bwiti and Magati villages.

Beautiful Kamba girl from Kenya

History

The ancestors of the Kamba can be said with some certainty to have come from the North, from the region beyond the Nyambene Hills to the northeast of Mount Kenya (Kirinyaga), which was the original if not exclusive homeland of all of central Kenya’s Bantu-speaking peoples, viz. the Kikuyu, Meru, Embu, Chuka, and possibly Mbeere. The people are believed to have arrived in the hills as early as the 1200s.

It is generally accepted that starting from around the 1500s, the ancestors of the Kamba, Kikuyu, Meru (including the Igembe and Tigania), Embu and Chuka, began moving south into the richer foothills of Mount Kenya. By the early 1600s, they were concentrated at Ithanga, 80km southeast of the mountain’s peaks at the confluence of the Thika and Sagana rivers.

Some also argue that the Kamba are a relatively new ethnic group, having developed from the merger of various Eastern Bantu communities in the vicinity of Mount Kilimanjaro around the 15th century. They are believed to have reached their present Mbooni Hills stronghold in the Machakos District of Kenya in the second half of the 17th century.

Kamba women | Antique Ethnographic Illustrations

In fact, as late as 1840, the Akamba were still migrating from what is present day Tanzania where many Akamba are said to have been arbsorbed by the Pare people. Al Masoudi, the Arab chronicler writing in AD 943, noted that the Zindj whom he encountered at the coast elected a king whom they called Falime. He also noted that, "there were among them (Zindj) with very sharp teeth." Sharpening teeth was a practice of the Akamba until very recently and it is likely that they were still trading with the coast as early as AD 943.

In the mid-eighteenth century, a large number of Akamba pastoral groups moved eastwards from the Tsavo and Kibwezi areas to the coast. This migration was the result of extensive drought and lack of pasture for their cattle. They settled in the Mariakani, Kinango, Kwale, Mombasa West ( Changamwe and Chaani ) Mombasa North ( Kisauni ) areas of the coast of Kenya, creating the beginnings of urban settlement. They are still found in large numbers in these towns, and have been absorbed into the cultural, economic and political life of the modern-day Coast Province. Several notable businessmen and women, politicians, as well as professional men and women are direct descendants of these itinerant pastoralists.

In the latter part of the 19th century the Arabs took over the coastal trade from the Akamba, who then acted as middlemen between the Arab and Swahili traders and the tribes further upcountry. Their trade and travel made them ideal guides for the caravans gathering elephant tusks, precious stones and some slaves for the Middle Eastern, Indian markets and Chinese markets. Early European explorers also used them as guides in their expeditions to explore Southeast Africa due to their wide knowledge of the land and neutral standing with many of the other societies they traded with.

Akamba Tribe Man Hunting Print by Africa Photos LUPE Photographe

Akamba resistance to colonial "pacification" was mostly non-violent in nature. Some of the best known Akamba resistance leaders to colonialism were: Syokimau, Syotune wa Kathukye, Muindi Mbingu, and later Paul Ngei, JD Kali, and Malu of Kilungu. Ngei and Kali were imprisoned by the colonial government for their anti-colonial protests. Syotune wa Kathukye led a peaceful protest to recover cattle confiscated by the British colonial government during one of their raiding expeditions on the local populations.

Muindi Mbingu was arrested for leading another protest march to recover stolen land and cattle around the Mua Hills in Masaku district, which the British settlers eventually appropriated for themselves. JD Kali, along with Paul Ngei, joined the Mau Mau movement to recover Kenya for the Kenyan people. He was imprisoned in Kapenguria during the fighting between the then government and the freedom fighters.

The Akamba are a very diverse group. Some groups claim that it takes a while to understand the dialects of other groups. Below is a selection of terms employed by the Akamba people to refer to others within the ethnic group.

i) The Akamba of Usu call the kitui Akamba - A -Thaishu

(ii) The Akamba of ulu call the A-kamba near Rabai, A-Tumwa and ma-philambua

(iii) The Akamba of kilungu call other Akamba – Evaao

The Maasai call the Akamba - Lungnu and the coastal people call the Akamba – Waumanguo due to their scanty dress.

Mkamba Woman Kenya Tanganyika 1963 postcard Sapra Studio

Hobley, a colonial administrator thought that “The Akamba are probably the purest Bantu race in British East Africa.” Since it is known today that the Akamba wondered far and wide in what is present day Tanzania, intermingling with the Wanyamwezi and the Wapare, Hobleys view may be taken with a pinch of salt.

Krapf who was the first white man to see the Mt. Kenya, courtesy of the Akamba, was the first European to interact and study their language and culture from within. He noted that the Akamba slaughtered a cow in a manner that was alien to him. He reported that:

“In the evening Kitetu slaughtered a cow to entertain the villagers; first the feet, then the mouth of the beast, were bound; the nostrils were stopped up, and so the poor animal was suffocated. I had not known that this was the usual way in which the Wakamba slaughtered their cattle.” (Wakamba is plural in Kiswahili. They would refer to themselves as Akamba and a single one as Mukamba).

The Akamba were skilled metal workers and one of the foremost Bantu group that introduced iron technology into East Africa. Krapf stated "The more precious metals have not yet been found in Ukambani; but there is an abundance of iron of excellent quality, which is preferred by the people of Mombaz to that which comes from India."

It should also be noted that recently, large iron ore reserves were discovered in the land of the Akamba. It is no wonder then the Akamba who all along had knowledge of these reserves settled in an area they named Kitui – place of iron working and had the best iron for miles.

It common knowledge today that the Akamba are gifted craftsmen. It has been theorised and many scholars accept that they learned their curving trade from the Makonde. But the fact is, the Akamba had been curving for Millenia and may have contributed to some the sculptures and figurines in Ancient Egypt. Here is an observation by Lindlblom, another colonial period scholar of the Akamba. “ Every head of a house makes the wooden articles that are needed such as beehives, stools, spoons, snuffbottles, handles of axes and knives...”

Lindblom also explained that while most stools are coarsely made three -legged “the same type as among the Akikuyu --” the ones meant for atumia are called ‘mumbo’ and as a special privilege they are’---neat and comfortable often real works of art. Great pains are taken in making them and they are usually adorned with copper or brass fittings.”

Atumia were revered Kamba elders. Every male ultimately reached this age-grade upon paying fees to the current Atumia, after he attained age 45 to 50.

Kamba people in their ethnic Kamba community (Ukamba wa kitui), Kiongwe Village

Economy

The Akamba were originally Long distance traders s, but later adopted agriculture due to the arability of the new land that they came to occupy.

Kamba farmers wedding their coffee farm

Today, the Akamba are often found engaged in different professions: some are agriculturalists, others are traders, while others have taken up formal jobs. Barter trade with the Kikuyu, Maasai, Meru and Embu people in the interior and the Mijikenda and Arab people of the coast was also practised by the Akamba who straddled the eastern plains of Kenya.

Kamba carvings. woodworkersjournal.com

Over time, the Akamba extended their commercial activity and wielded economic control across the central part of the land that was later to be known as Kenya (from the Kikamba, 'Kiinyaa', meaning 'the Ostrich Country'), from the Indian Ocean in the east to Lake Victoria in the west, and all the way up to Lake Turkana on the northern frontier. The Akamba traded in locally-produced goods such as cane beer, ivory, brass amulets, tools and weapons, millet, and cattle. The food obtained from trading helped offset shortages caused by droughts and famines.

Kamba Tribe Decorative Gourd Bowl Set of 2 (Kenya

They also traded in medicinal products known as 'Miti' (literally: plants), made from various parts of the numerous medicinal plants found on the Southeast African plains. The Akamba are still known for their fine work in wood carving, basketry and pottery. Their artistic inclination is evidenced in the sculpture work that is on display in many craft shops and galleries in the major cities and towns of Kenya.

Kamba wood works

Kamba Society

Although a large part of Kamba culture has become westernized, and the large towns and villages have greatly increased in number (the Kamba population itself is now five times larger than it was in the 1930s), the traditional pattern of family homesteads persists, and is one of the few traditional social structures to have survived the twentieth century. Other forms of social and political structures - such as clans, councils of elders, and age-sets - now appear to be primarily historical, and are no longer in use.

Family: In Akamba culture, the family (Musyi) plays a central role in the community. The Akamba extended family or clan is called mbai. The man, who is the head of the family, is usually engaged in an economic activity popular among the community like trading, hunting, cattle-herding or farming. He is known as Nau, Tata, or Asa.

The woman, whatever her husband's occupation, works on her plot of land, which she is given upon joining her husband's household. She supplies the bulk of the food consumed by her family. She grows maize, millet, sweet potatoes, pumpkin, beans, pigeon peas, greens, arrow root, cassava, and yam in cooler regions like Kangundo, Kilungu and Mbooni. It is the mother's role to bring up the children. Even children that have grown up into adults are expected to never contradict the mother's wishes. The mother is known as Mwaitu ('our One').

Very little distinction is made between one's children and nieces and nephews. They address their maternal uncle as naimiwa and maternal aunts as mwendya and for their paternal uncle and aunt as mwendw'au. They address their paternal cousins as wa-asa or wa'ia (for men is mwanaasa or mwanaa'ia, and for women is mwiitu wa'asa or mwiitu wa'ia), and the maternal cousins (mother's side) as wa mwendya (for men mwanaa mwendya; for women mwiitu wa mwendya). Children often move from one household to another with ease, and are made to feel at home by their aunts and uncles who, while in charge of their nephews/nieces, are their de facto parents.

Grandparents (Susu or Usua (grandmother), Umau or Umaa (grandfather)) help with the less strenuous chores around the home, such as rope-making, tanning leather, carving of beehives, three-legged wooden stools, cleaning and decorating calabashes, making bows and arrows, etc. Older women continue to work the land, as this is seen as a source of independence and economic security. They also carry out trade in the local markets, though not exclusively. In the modern Akamba family, the women, especially in the urban regions, practice professions such as teaching, law, medicine, nursing, secretarial work, management, tailoring and other duties in accordance with Kenya's socioeconomic evolution.

Prof Makau W. Mutua, former cabinet minister, former Dean of Law Faculty University Of Nairobi and current Governor Makueni is from Kamba tribe in Kenya

Age-Sets: Individuals were organized in age-sets, but unlike the Kikuyu, Embu, Mbeere and Chuka, these were not based on initiation.

Men and women of the grade of elders (atumia) formed political district councils that governed several utui. They also performed the function of priests, acting as ceremonial intermediaries between the living and God or the spirit-ancestors.

Clans: The Kamba were originally grouped into some 25 dispersed patrilineal clans (utui) of varying size, which were often mutually hostile. The Akamba have 14 major clans and 11 minor clans. This makes a total of 25 clans. When a family grows into a clan, it is natural that the clan grows and separates into several clans. This did happen to the Akamba.

Their social and territorial boundaries were flexible, and the system seems more to have been a response to fluid geographical groupings rather than strictly determined by ancestry or tradition. There seem to have been few if any institutions of centralized political authority, although in times of external threat, military action could be coordinated across the whole tribe.

Clan meetings were called mbai, and through them political matters that affected the whole tribe were decided. The British abolished the system in the nineteenth century, imposing appointed leaders instead. Nowadays, elections and modern politics are the usual source of political power.

Below is a list of the twenty-five clans of the Akamba.

The 14 Major Clans include: Akanga, Aketdini, Aketutu, Ambuane, Amoei, Amoieni, Amotei – trappers, Anzaone, Anzio, Asii, Atangoa, Atui – blacksmiths, Eembe and Ethanga.

The 11 Minor Clans are: Adine, Akeimei, Akuu, Amena, Amokabu, Amomone, Amooi, Amouti, Anilo, Aoani, Athonzo

Marriage (Ntheo): The Akmaba have deep-rooted traditions, which are practiced especially in their marriage customs. Under the Kamba customs, during a Kamba wedding, a man must show his respect for the bride’s family by first acknowledging that their girl has been brought up well and is therefore of great worth.

Before a marriage ceremony is conducted, the groom (with his kin) must throw an important party popularly referred to as Ntheo. Ntheo is actually the minimum requirement that demonstrates the bride officially belongs to the man she is engaged to.

In case the couples are in a "come-we-stay" arrangement, meaning there was no advance ceremony before they began living as husband and wife, the entire marriage is deemed null and void under the Kamba customary law.

As a result, the woman in the marriage is considered an illegitimate wife and the man illegitimate husband. If, and God forbid, a woman whose husband is yet to throw the ntheo party to her (bride`€™s) kin dies, she cannot be buried by her husband no matter how long she had stayed with him. And if the husband finds it important to bury the remains of his wife at his home, he has to carry out the ntheo ceremony before the burial.

An ordinary ntheo ceremony involve at least three goats, one of which must be a he-goat that is un-castrated. However, you may have more than three goats but the rule is that the number of the animals to be presented to the bride`s family for the purpose of ntheo must add up to an odd number. This means the goats may be five, seven, nine and so on but not four or six!

During this ceremony, only a handful close relatives of both sides of families are involved. The he-goat is then slaughtered by the groom, or alternatively a brother to the groom. It is believed that as soon as blood of the he-goat spills on the ground, the bride becomes "officially owned" by the groom that very moment. But it does not end there. A piece of soft meat popularly known as kikonde, extracted from the slaughtered goat is given to both the bride and groom, who must eat at least a piece each as "an oath" that they will keep the covenant of their marriage.

In case ntheo ceremony is carried out before a marriage ceremony like it is the case in most Christian marriages, the bride is deemed to already "lawfully" belong to her fiance under Kamba customary law. And even if there is no church ceremony the two are deemed married.

Once food is served to those present at the ceremony, women and children are issued with soft drinks while men who are considered mature are served with Kaluvu, the Kamba traditional beer. It is important to note it is the groom`s responsibility to ensure both types of drinks are made available in acceptable quality and quantity. Once the ntheo ceremony is done, the process of "€˜buying a wife"€™ begins there and then. The bride`s kin are to present the numerous items the bride`s family will require as dowry.

Kamba tribes man, Mwendwa Kitili dancing with his wife. He was Kenya's youngest and first African Chief Justice

However, these items may be paid through installments that are usually negotiated at friendly basis by the two sides of the families. Dowry is what is popularly referred to as ngasya. Coming on the top of the list of items for ngasya are 48 goats, which must eventually be delivered to the bride’s family. This means, for instance, if the groom used three goats for the ntheo ceremony, he is left with an outstanding balance of 45 goats.

Also in the list of dowry items are two drums of honey referred to as Ithembe, two blankets as well as two bed sheets. These may be issued physically or monetary compensation offered against each item. Another interesting item that features prominently in the list of dowry items is a big goat called ndua itaa brought to the bride`s parents. This one is supposed to signify that the bed that belonged to the bride while at her parents`€™ home has now been bought by the groom`s family. To crown the marriage, the groom is also expected to throw yet another mega party to the in-laws, and this time the entire village is invited to feast. A huge, castrated bull is slaughtered and friends and neighbours are invited for a ceremony dubbed ilute. During this ceremony, the bride is showered with gifts by members of her kin and friends alike, which she may take to her matrimonial home. Divorce: But what if the worst happens and the groom intends to divorce his wife? The groom will have to incur another cost again! Under Kamba tradition, the groom (together with his parents) must take two goats, one male and another female called mbui sya maleo (goats of divorce) to the bride`s family. The groom`s family may opt to claim all what they incurred in dowry payments after "deporting" the bride to her parents` home, or just forget about it altogether!

Childbirth: During the last three months of her pregnancy, the expectant mother was also forbidden to eat fat, beans, and the meat of animals killed with poisoned arrows. In addition, she ate a special kind of earth found on termite hills (termitariums) or on trees. This earth is first chewed by termites, then deposited on trees and grass, or piled up to form a mound. When eaten, such 'earth' strengthens the body of the child.

Before giving birth, all weapons and iron articles were removed from the house of the expectant mother, as it was believed that iron articles attracted lightning (both, one might presume, physical and 'spiritual', the latter in the form of evil spirits).

When a child is born, the parents slaughter a goat or bull on the third day. Many people come to feast and rejoice with the family, and women who have borne children get together to give a name to the child. This is known as 'the name of ngima', ngima being the main dish prepared for the occasion.

On the fourth day, the father hangs an iron necklace on the child's neck, after which it is regarded as a full human being and as having lost contact with the spirit world. Before that, a child is regarded as an 'object' belonging to the spirits (kiimu), and if it should die before the naming ceremony, the mother becomes ritually unclean and must be cleansed.

During the night following the naming, the parents perform ritual sexual intercourse, which is the seal of the child's separation from the spirits and the living-dead, and its integration into the company of human beings.

Circumcision and clitoridectomy: Circumcision and clitoridectomy remain important among the Kamba, and through them a child attains adulthood. In some parts there are two separate stages: the "small" ceremony (nzaikonini), which occurs when the child is between four and five years old and the "big" ceremony (nzaikoneni), which occurs when the child reaches puberty and is a more prolonged period of initiation.

Female circumcision, which was officially banned by the Kenyan government in 1981, is still widely practised.

Naming and Akamba names

Naming of children is an important aspect of the Akamba people. The first four children, two boys and two girls, are named after the grandparents on both sides of the family. The first boy is named after the paternal grandfather and the second after the maternal grandfather. Girls are similarly named. Because of the respect that the Kamba people observe between the varied relationships, there are people with whom they cannot speak in "first name" terms.

The father and the mother in-law on the husband's side, for instance, can never address their daughter in-law by her first name. Neither can she address them by their first names. Yet she has to name her children after them. To solve this problem, a system of naming is adopted that gave names which were descriptive of the quality or career of the grandparents. Therefore, when a woman is married into a family, she is given a family name (some sort of baptismal name), such as "Syomunyithya/ng'a Mutunga," that is, "she who is to be the mother of Munyithya/Mutunga."

Her first son is to be called by this name. This name Munyithya was descriptive of certain qualities of the paternal grandfather or of his career. Thus, when she is calling her son, she would indeed be calling her father in-law, but at the same time strictly observing the cultural law of never addressing her in-laws by their first names.

After these four children are named, whose names were more or less predetermined, other children could be given any other names, sometimes after other relatives and / or family friends on both sides of the family. Occasionally, children were given names that were descriptive of the circumstances under which they were born:

*"Nduku" (girl) and "Mutuku" (boy) meaning born at night,

*"Kioko" (boy) born in the morning,

*"Mumbua/Syombua" (girl)and "Wambua" (boy) for the time of rain,

*"Wayua" (girl) for the time of famine,

*"Makau" (boy) for the time of war,

*"Musyoka/Kasyuko/Musyoki" (boy) and "Kasyoka/Kasyoki" (girl) as a re-incarnation of a dead family member,

*"Mutua" (boy) and "Mutuo/Mwikali" (girl)as indicative of the long duration the parents had waited for this child, or a lengthy period of gestation.

Children were also given affectionate names as expressions of what their parents wished them to be in life. Such names would be like

*"Mutongoi" (leader),

*"Musili" (judge),

*"Muthui" (the rich one),

*"Ngumbau" (hero, the brave one).

Of course, some of these names could be simply expressive of the qualities displayed by the man or woman after whom they were named. Very rarely, a boy may be given the name "Musumbi" (meaning "king"). I say very rarely because the Kamba people did not speak much in terms of royalty; they did not have a definite monarchical system. They were ruled by a council of elders called kingole. There is a prophecy of a man, who traces his ancestry to where the sun sets (west) (in the present day county of Kitui) who will bear this name.

A girl could be called "Mumbe" meaning beautiful. Wild animal names like Nzoka (snake), Mbiti (hyena), Mbuku (hare), Munyambu (lion), or Mbiwa (fox); or domesticated animal names like Ngiti (dog), Ng'ombe (cow), or Nguku (chicken), were given to children born of mothers who started by giving stillbirths. This was done to wish away the bad omen and allow the new child to survive. Sometimes the names were used to preserve the good names for later children. There was a belief that a woman's later children had a better chance of surviving than her first ones.

Ethnic Kamba boy from Kiongwe village in Kenya

Religious Belief

The Akamba believe in a monotheistic, invisible and transcendental God, Ngai or Mulungu, who lives up in the sky (yayayani or ituni). Another venerable name for God is Asa (the strong Lord or the Father). He is also known as Ngai Mumbi (God the creator, fashioner or maker), na Mwatuangi (God the 'distributor' or 'cleaver', from the human act of slicing meat with a knife or splitting wood with an axe), and Mlungu ('creator'), which is the name most commonly used in East Africa for the creator God, and exists as far south as the Zambesi of Zambia.

Ngai or Mlungu is perceived as the omnipotent Creator of life on earth, Protector and as a merciful, if distant, entity. The Kamba say that God does to them only what is good, so they have no reason to complain. He protects people, and is known as both 'the God of comfort' and 'the Rain Giver' (rain is sometimes called the 'saliva of God', and for this reason to spit on something (such as a child) is a symbol of great blessing).

At planting time, the Kamba ask God to bless their seeds and their work on the fields, and as a God of consolation and sustenance, He intervenes when human help is slow or ineffective.

The Kamba consider the heavens and the earth to be the Father's 'equal-sized bowls': they are his property both by creation and rights of ownership; and they contain his belongings, including livestock, which he lowered from the sky and gave (perhaps 'lent' is more correct) to the Kamba.

The traditional Akamba perceive the spirits (kiimu) and spirits of their departed ones, the Aimu or Maimu, as the intercessors between themselves and Ngai Mulungu. They are remembered in family rituals and offerings / libations at individual altars.

Spirits (Kiimu): It is said that some spirits were created as such by God, whilst others were once human beings: the spirits of deceased ancestors, who are also known as the 'living-dead'. God controls them and sometimes sends them as his messengers. Some are friendly and benevolent, others are malevolent, but the majority are 'neutral' or both 'good and evil', like human beings.

Nonetheless, in traditional life, families are careful to make libation of beer (uki), milk or water, and to give bits of food to the living-dead, in order to appease the ones that may wish to do harm to the living.

Some diviners and medicine-men receive instruction through dreams or appearance of the spirits and the living-dead, concerning diagnosis, treatment and prevention of diseases, although when healing comes, it is often attributed to God, even if medical agents (or spirits) may have played a part in the healing process. After recovery from a serious illness, the Kamba say 'Ah, if it were not for God's help, I/he would be dead by now!'.

Spirit possession by both the spirits and the living-dead is commonly reported, though less now than in previous years. Around the turn of this century, there was an 'outbreak' of spirit possession in the southern part of the country, when the phenomenon 'swept through the communities like an epidemic'. It is believed that some women have spirit 'husbands' who cause them to become pregnant.

A considerable number of people still report seeing spirits and the living-dead, both alone as individuals and in groups with other men or women. They are usually spotted along hillsides or in river beds. In such places, their lights are seen at night, their cattle heard mooing or their children crying. Mbiti, the great African traditional religious scholar mentions two such experiences, as recounted by two pastor friends of his:

"One of them was walking home from school with a fellow schoolboy in the evening. They had to cross a stream, on the other side of which was a hill. As they approached this stream, they saw lights on the hill in front of them, where otherwise nobody lived. My friend asked his companion what that was, and he told him not to fear but that it was a fire from the spirits. They had to go on the side of the hill, and my friend was getting frightened. His companion told him that he had seen such fires before, and that both of them had only to sing Christian hymns and there would be no danger to them. So they walked on singing, and as they went by the hill, the spirits began tossing stones at them. Some of the stones went rolling up to where the two boys were walking, but did not hit them.

As the young men were leaving this hill, they saw a fire round which were shadowy figures which my friend's companion told him were the spirits themselves.

Some of the spirits were striking others with whips and asking them, 'Why did you not hit those boys?', 'Why did you not hit them?' The two young men could hear some of the spirits crying from the beating which they received, but did not hear what reason they gave for not hitting the boys with stones."

He cited another example:

"The other pastor told me that when he was about twenty, he went with several other young men into a forest to collect honey from the bark of a withered tree. The honey was made by small insects which do not sting, and which are found in different parts of the country. The place was far away from the villages. When they reached the tree, he climbed up in order to cut open the barks and the trunk of the tree. While up on the tree, he suddenly heard whistling as if from shepherds and herdsmen. He stopped hitting the tree. The group listened in silence. They heard clearly the whistling and the sound of cattle, sheep and goats, coming from the forest towards where they were collecting honey. The sound and voice grew louder as the spirits drew nearer, and the young men realized that soon the spirits would reach them. Since people do not graze animals in forests but only in plains, and since the place was too far from the villages for men to drive cattle through here, the young men decided that only the spirits could possibly be approaching them. They looked in the direction from which the sound came, but saw nobody, yet whatever made that sound was getting nearer and nearer to them. So the men decided to abandon their honey and flee for their lives. They never returned to that area again."

Sacrifice: The Kamba make sacrifices on great occasions, such as at the rites of passage, planting time, before crops ripen, at the harvest of the first fruits, at the ceremony of purifying a village after an epidemic, and most of all when the rains fail or delay. They use oxen, sheep or goats of one colour, and in the case of severe drought they formerly sacrificed a child which they buried alive in a shrine.

The shrines themselves are unobtrusive, traditionally being forest clearings containing either a large or otherwise sacred tree (such as the fig tree), or other notable natural objects, such as unusually smooth or polished bounders. The trees may not be cut down, and the shrines are regarded as a sanctuary for animals and humans alike (including criminals, if they dare enter them - the fear of reprisal from spirits is great). The idea is similar to the sacred kayas of the Mijikenda, and the sacred groves of the Embu and Mbeere.

Kamba woman

Proverbs and Riddles

1. Wikuma wilika. Despite your bark, you'll be eaten! It means like braggarts, cowardly dogs bark a lot. Prowling leopards easily spot and eat them.

2. U wi kivetani nduthekaa ula wi iko. (One in the woodpile does not laugh at one in the fire). It means don't laugh! You may be next.

3. Too umanthaa na awe. (Only a medicine man gets rich by sleeping). it means with money in hand, clients will wake him up.

4. Nguli syonthe itiania musoani. (All monkeys cannot hang on one branch). It means people differ

5. Ki kitungaa mutumia ndithya ndakisi. (An old man doesn't know what makes him herd again) It means old Kamba men rarely herded; their sons and grandsons did.

Kamba tibe`s man Benson Masya (14 May 1970 – 24 September 2003) was a Kenyan long-distance runner and marathon specialist, who competed in the late 1980s and 1990s. He participated at the inaugural IAAF World Half Marathon Championships in 1992 and finished in first place.

#Riddles (Ndae)

Kikamba English

1. Question: Kungula kangala kithembeni? Kungulu kambagal (noise) in the drum?

Answer : Mutwaano wa mbia A wedding of rats

2. Question: Nayiatha na kaluma ndiu ndukakwata? It's in space, and you can't touch the eagle eater?

Answer: Ndata A star

3. Question: Kaveti kaa kanini kakilitye mwenyu kuua? This small woman cooks better than your mother?

Answer: Nzuki A bee

4. Question: Kikungu muingo? Dust on the other ridge?

Answer: Nzana isembee mwana A monitor lizard running for its child

5. Question: Masee ma asa meanene? My father's two equal calabashes?

Answer: Itu na nthi Earth and sky

Kamba dance

Music and Dance

Undoubtedly the most spectacular manifestation of traditional Kamba culture was their dancing, performed to throbbing polyrhythmic drum beats. It was characterised by exceptionally acrobatic leaps and somersaults, which flung dancers into the air. The style of playing was similar to that of the equally disappeared traditions of the Embu and Chuka: the drummers would hold the long drums between their legs, and would also dance. The Kambas of Paraguay in South America still perform this traditional dance.

Kamba musicians

From the 1960s, groups like Kilimambogo Brothers of the late Kakai Kilonzo, Mateo Festos of Muema Brothers and Peter Mwambi of Kyanyanga Boys Band have composed hit songs that captivated not just Ukambani but the entire country.

Unfortunately, with the exception of official functions and music festivals (where professional cultural troupes perform), Kamba dancing is now almost if not completely extinct. With the exception of one commercially available tape ("Akamba Drums", Tamasha), I failed to find any tapes of drum music, nor any reference to existing groups. The only live 'Akamba' drumming I heard was a pale imitation by a touristic multi-tribal ensemble on the coast, whose authenticity was inevitably suspect.

Several of the dances had military themes, directly derived from the participation by Kamba in large numbers in the country's armed forces, starting with the First World War when they served under the British in India and the Middle East.

The Musical Bow - Uta wa mundu mue: The Kamba musical bow is similar to those of other peoples, consisting of a tautly-strung bow, to which is attached a gourd resonator. The playing technique is, however, unusual: whilst beating the string with a stick to produce a single note, the performer sings into the hollow gourd.

The instrument was played by medicine men while treating patients, and the Kamba name for the instrument - uta wa mundu mue - literally means 'the bow of the medicine man.'

Drums - Ngoma: Ngoma served three main purposes in Kamba life, and each purpose could be determined by the beat (the following is adapted from the sleeve notes to "Akamba Drums"):

1. Three heavy drum beats and a two- to three-minute break sounded a warning to the village of an approaching enemy.

2. A single continuous beat was meant to remind villagers that it was time to meet somewhere, from where all would go and help cultivate the shamba (farm) for a colleague of theirs.

3. A heavy single stroke of the drum, followed by a continuous whistling was a call from help from the neighbours when for instance a hut was on fire or cattle rustlers had raided a cattle boma (enclosure).

Whenever the Ngoma drum was used in celebrations, it was first warmed in the sun to attain the correct timbre. During the dance a number of them could be used.

Drum dances - Kilumi: Kilumi (pl. milumi) drum songs and dances were traditionally performed by women and comprised of two kilumi drums accompanying the ululations and singing of a lead singer backed by two other women vocalists. Usually, the drummers compose and sing too.

Formerly for old women, kilumi is now danced to even by men, and kilumi is one of the few songs and dances that traditionalists still perform in Ukambani. One session of the kilumi dance could last about half an hour, and the entire performance for something like eight hours.

Laughing at something

Museve Muumbi was carried down by water,

I came with Nzambi.

Don't forget, he knows what I want.

You will thatch with grass please. Muumbi drowned.

A slithering snake drowned. You will thatch with grass. Oh yes!

You will thatch with grass. Muumbi drowned. I came with Nzambi.

What do you know?

I was laughing at something. Soon it will be morning.

Iii of Mulovi of Walii and Ngata,

let me work like white men. What is it?

I will want to greet Walii,

Iii. Aiiiii. He is possessed! [spoken]

I will want to greet Walii,

Iii. Aiiiii. He is possessed! [spoken]

Do you know, I laugh at something I want. Walii and Ngata, if I want to, I'll call on you in the evening. Haieeee!

Other drum dances:

The following is adapted from the sleeve notes to "Akamba Drums".

Mbeni: This dance is for young unmarried people and because of its tiring pace, it has the shortest sessions. One session lasts less than ten minutes. Its instruments are a set of four drums and three whistles. Danced in pairs as it gets to the climax, when the male dancer (Anake) jumps about four feet into the air and somersaults.

Kamba mbeni dance

Nduli: The most popular dance among Kamba teenagers. It is a condition that any boy attending an Nduli session must be circumcised, for it is in the Nduli dance that one may choose a partner for life.

Kisanga: This is a thanks-giving dance for all ages, both young and old. It is performed only when the village has had a good harvest. During the celebration a white goat is slaughtered, its blood poured under the Kitutu Tree, and its meat left near the tree for Mulungu (God).

Mwasa: The Mwasa dance involved two drums, one small and one large, and was found in northern Kitui. While not primarily used for dancing, Mwasa served as an accompaniment while elders enjoyed uki beer. Mwasa is a relatively new drum beat, which comes from a combination of Nzumari from the Giriama (one of the 'Nine Tribes' of the Mijikenda) and original Kamba Ngoma. It came into existence during the Second World War, when Giriama and Kamba soldiers served together in the colonial army.

Kamba Mwasa dance

Songs

The Kamba have many kinds of songs; and each type has a name. The songs included: mbathi sya kivalo; myali (general social commentary and scathing attacks [nzeo] against miscreants); lullabies; and songs for circumcisions, marriages, work, and hunts (uthiani). Circumcision songs had many names: ngakali (or kakali) and undiu. Unmarried girls sang maio ("mourning" songs) at a newly married girl's home to "mourn" losing their colleague. While thatching, threshing or digging, people commonly worked to the rhythms of songs.

Mbathi sya kivalo were wathi songs accompanied by dance and, often, instrumental music. These songs differed according to the dance steps and drums used. Songs accompanied by instruments included kyaa, ngutha, mbalya, kuli, mbeni, kilumi and ngulukulu. Unaccompanied songs included nzai, kithakyo, musya, kilamu, mukungo, kilui, kileve, mawese and mbalu.

Myali (singular mwali) were sung at wathis - big ceremonies with singing, dancing, and socializing. Myali were neither accompanied by musical instruments nor danced to in Machakos and Kitui Central. At the wathi, myali were sung during interludes between dances. They were also sung at weddings, after work, or simply for leisure. They were composed and sung throughout the year, even when wathi was out of season. Though every Kamba might sing myali, few composed them. The mwali composer (ngui) would sing a recent composition, sometimes on request [...]

Though wathis are not held in most of Ukambani, myali are still sung in small informal groups. The ngui and mbasa interviewed during this research reported that ngui were no longer composing new myali. More thorough research is needed to reveal whether these customs have survived in some parts of Ukambani.

Traditionally, myali covered events, experiences and attitudes of the Kamba - conserving traditions and defending customary mores. Besides entertaining, mwali also conveyed the Kamba's aspirations, hopes and fears. The language in myali was highly figurative with many metaphors, similes, and innuendos using imagery common to the people and their surroundings. Multiple themes were portrayed easily since one word or phrase could have several meanings at different levels. Thematically, myali were remarkably eclectic; each mwali dealt with multiple themes simultaneously. In rapid fire, the apparent focus shifted abruptly, though - through hidden references - major themes continually resurfaced. This made myali difficult to understand because certain words or phrases could be taken literally with deeper meanings eluding casual listeners. People were challenged to decipher the meanings of the things, places and persons alluded to. These disguised references made myali both difficult and popular; they were often codes understood by an intended few. By choosing words or occurrences known to few people, a ngui could conceal many ideas and messages, though he sang publicly.

Myali extolled exceptional feats by individuals or groups and denounced deviant actions or behaviour, especially in nzeo ("to slice off"), a subclass of myali. Nzeo helped Kamba society discipline wrongdoers, rogues, and social misfits. Society, with its many eyes, swiftly exposed villainous behaviour. The culprits were named, and quickly, in the regular form provided by wathi. Traditionally, the Kamba were not at all reluctant to name publicly any wrongdoer. And everyone dreaded the scorn and wrath that ensued such public exposures. Once sung, people would remember and sing those nzeo long afterwards during wathi and while relaxing, walking, or working, especially when in earshot of the culprit. Psychologically, the peer-group pressure was immense; and people feared committing any transgression that might inspire a ngui to sing a nzeo against them.

With sharp satire - currently an under used skill - myali seriously criticized society. For example, a torrent of myali condemned colonial oppression and exploitation. Myali helped mobilize people against the colonialists, though previous researchers have largely overlooked this function. Since myali was a major device for Kamba society to maintain its cohesion, discipline, and moral fibre, the colonialists' prohibition of wathi - the main fora for myali - struck a vital blow to the Kamba's ability to resist military and cultural domination, eg., orders to burn their traditional adornments and clothing.

A novice ngui emulated older ngui and learned from their compositions. The budding ngui would compose a mwali and sing it to himself and his friends outside the wathi before being officially introduced at a wathi. A new ngui had to be recognized by elders and prominent ngui who would endorse him at the wathi.

The ngui respected and mentioned each other in their compositions, thereby recognizing each other's talents and demonstrating professional solidarity. Occasionally, ngui competed against each other. Each ngui was listened to individually. They insulted one another, calling each other names and pointing out their faults as a person and a ngui. They used subtle words only their age mates understood. But this was just a mock rivalry rarely extending beyond the wathi.

A ngui's competence and artistic creativity was measured by how accurately he portrayed events, occasions or deeds. Originality and imaginative use of the language proved his artistic ability. By ingeniously manipulating the language, a ngui became distinguished. Though composition of a mwali was usually inspired by a specific event, the mwali also referred to other events the ngui had observed or heard about.

Each ngui chose one or more men (mbasa) to help him sing. He composed a mwali on his own, sometimes isolating himself for days, depending on how quickly the mwali was formed. Then he called his mbasa and sang the song repeatedly until they memorized it later, the ngui and his mbasa attended the wathi and sang the new composition. A mbasa never composed or altered myali; they only sang with their ngui. A mbasa accompanied the ngui at all his performances. He carried the ngui's stool and skin and any gifts received. After singing at a function (eg., a wedding or feast), the ngui and his mbasa were fed kituma, a specially prepared chicken.

Wathi was the most significant social occasion among the Kamba before colonialism. During a wathi, people gathered, sang and danced in the kituto or kinyaka, a specially cleared piece of land between two or three villages. People mingled at the wathi; and many youths met their future spouses. Wathi was organized by nthele selected by older men and women. Wathi happened during the dry season and was forbidden during planting, weeding and harvesting times. At the wathi, both individuals and groups sang with or without musical instruments, usually drums. Many types of drums were used for different dances.

Different villages sometimes held dance competitions. Charms and magic were used to win the competitions, supposedly by lessening the opponents' vigour in dancing or by successfully deflecting an opponent's jinx.

Between January and March, wathi wa muvingusyo (song of knocking) occurred. This kind of wathi happened at night. It started at the homesteads with youths singing loudly while gathering their friends and moving from village to village. Being free to wander at night, young men serenaded outside girls' huts. A girl's father would tell the group: "Stop clamouring, leave the compound." This signalled that he would allow his daughter to go with them. If he said nothing, the youths would wait patiently, later leaving without her, but reluctantly. After many youths joined the procession, they went to the kituto or any open space nearby where the wathi continued till dawn.

After the harvest and circumcisions, wathi was at its peak. Dancing was specifically for the young. A man could dance until his children were adolescents; afterwards he could only watch. Married women, especially those who had borne more than two children, were usually spectators, not dancers. Each participant at the wathi had a wathi-name given by his peers. After marriage, women's wathi-names were dropped, though men kept theirs.

For the wathi, young men and women adorned themselves with different ornaments collectively called mathaa, eg., masango, mavuo, masoa, milia, ndini, syuma, ndulo, nganyange, mamile, mbangili, ikuli and imaba.

Kamba women drummers

Hunting songs: The following hunting song is called Uthiani. After a successful hunt (or raid), the hunters or warriors received a bull - the "unity" (muamba) bull - to eat.

"Due to relishing heart and eating bone marrow, I was broken.

Mwania's father's [cattle] were raided with a pronged stick.

Iii iiii mmmmm.

Though I might fail, I'll try to touch the breasts of the coward's wife.

Yes! Unity and co-operation were destroyed due to relishing heart and eating bone marrow. Mwania's father's [cattle] were rustled with a pronged stick.

Iii iiii mmmmmmm.

I'll hunt deep into the forest till

I find them at Makala's digging up roots for the baby.

I don't want people saying I feared elephants.

Quiver-carrier, if you fear elephants and yet have no wife, with what will you buy her?

You fear elephants though they have not adorned themselves with masango [a type of necklace].

Bang! Kisove's hunt in Mbitini! [spoken]"

Lullabies: Women sang or sometimes just hummed short lullabies over and over again to restless or crying babies. The following is called "Rain".

"Every worldly thing rejoices about rain. It is the mother of all the things God created.

Lululu, baby sleep.

Lululu, baby stop crying, rain is coming.

Lululu, baby stop crying, rain is coming."

Wedding songs: This wedding song is entitled "Leave your friends, forget the dances!". A soloist sings each line twice, and the chorus repeats it twice.

"Moses, you are now married.

You should know, you are now an elder.

Forget your old companions.

Moses, you have done a good thing for us.

You need to know, you are now an elder.

Forget your old companions.

Stop going to the dances you went to.

Stop going to the movies like you did before.

Aggy! Aggy is married. Know that you are now a wife.

Leave your former friends. Forget the dances you used to attend.

Know that you are now a wife.

Mutiswa! Mutiswa has "gone up".

Fetchers of firewood have increased. The community has grown.

Mambwa has slept.

The community [of young unmarried women] is now one less."

Work songs :This song, entitled "To Gatundu to see Kenyatta", was sung as a solo to provide a rhythm for road-building, which was a form of forced labour imposed by the British.

"Iii hep!

Have you heard?

Let's go to Gatundu to see Kenyatta. The people from Kithini never built a shop. Yes, have you heard?

The following, called "Don't forget me!", is also sung by a soloist, and accompanied the tiring task of grinding grain.

"Nzakyo, you will get me arrested.

Nzakyo, Mbuvi's son! Yes, you will get me arrested.

Tell me what is on your mind. I'm crying.

As I open and close my eyes, tears just pour out.

Now, I am getting ready to travel like the governor's plane, the plane destined for Mwanza.

Now, I am getting ready to travel like the governor's plane, the plane destined for Mwanza."

Kamba musical group that play in a style of Kilumi, wathi wa kikamba. They are also from the Kamba ethnic community (ukamba wa kitui).

Clothing

The Akamba of the modern times, like most people in Kenya, dress rather conventionally in western / European clothing. The men wear trousers and shirts. Young boys will, as a rule, wear shorts and short-sleeved shirts, usually in cotton, or tee-shirts. Traditionally, Akamba men wore leather short kilts made from animal skins or tree bark. They wore copious jewellery, mainly of copper and brass. It consisted of neck-chains, bracelets, and anklets.

The women in modern Akamba society also dress in the European fashion, taking their pick from dresses, skirts, trousers, jeans and shorts, made from the wide range of fabrics available in Kenya. Primarily, however, skirts are the customary and respectable mode of dress. In the past, the women were attired in knee-length leather or bark skirts, embellished with bead work. They wore necklaces made of beads, these obtained from the Swahili and Arab traders. They shaved their heads clean, and wore a head band intensively decorated with beads. The various kilumi or dance groups wore similar colours and patterns on their bead work to distinguish themselves from other groups.

Serena Williams being dressed as traditional Kamba woman

Traditionally, both men and women wore leather sandals especially when they ventured out of their neighbourhoods to go to the market or on visits. While at home or working in their fields, however, they remained barefoot.

School children, male and female, shave their heads to maintain the spirit of uniformity and equality. Currently the most popular Kamba artist include; Ken Wamaria, Kativui, Kitunguu etc. Ken Wamaria is rated as the top artist in Ukambani and the richest Kenyan artist (Kioko, 2012).

Death and afterlife

In common with many other Kenyan people, the Kamba have various legends that say that the first men had the gift of either immortality or of rising again after dying. God one day decided to make this permanent, so he called for a messenger. The people sent a very slow but careful animal, such as a chameleon or mole, to receive and deliver the message. As it was God's message, once it was delivered, it could not be taken back. Alas, on his way back down to earth, the animal either forgot the message, or foolishly blurted it out to an envious animal, such as jackal, who then ran to tell the people the opposite of what God had commanded. Henceforth, people were condemned to die and never rise again. As you can perhaps tell, I don't have a Kamba example of the tale, so have a look at the Kikuyu myth of the Origin of Death, which is similar.

The first myth goes like:

"Now there was a time when men rose again as soon as they died. One day Ngai sent the chameleon to tell people that they would never die. Ngai wanted people to multiply on the land. He said: 'Go. Tell the people that from now one they will not die. They will bear more children and the land will be populated.'

The Chameleon went on his errand but he walked very very slowly, treading very softly. He did not want the vault of the earth to collapse. Now when he reached the earth, he found that the people were waiting to hear the message he had brought. And the chameleon started to deliver his message in this manner: 'I wa-was-was to-told, I wa-wa-was to to-told...'

And the people waited to hear what the Chameleon wanted to say.

Now as the people were waiting for the message, Ngai sent the swift flying Nyamindigi. The latter came and found that the Chameleon had not finished his message and the bird said:

'What is this you are telling the people?'

'I was-was-was-to-to-told, were they not told to die and vanish from the earth?'

And the bird flew away. The Chameleon was left humiliated and feeling guilty because he did not deliver his message soon enough. Now from that day people died and never returned again to earth.

When people saw the Chameleon, they mocked and despised him saying: 'Get thin and thinner and let me grow fat and healthy.'

And the Chameleon constantly grew thinner and wasted away. The story ends there.

The second myth also goes like:

"It is Riua (Sun) the King of the Earth who lives at Kirinyaga who came to earth and found the chief's son dead. The chief told the King that death had become a great problem to his people. And Riua the King said: 'Give me a messenger, I will give him a medicinal powder from Kirinyaga. This powder will be put in the fire and when people smell its smoke, they will never die again.'

The chief chose the squirrel and when the women saw the squirrel dressed up to go with Riua the King, they were jubilant and ululated: 'Aririririi-ri-i'. The squirrel appreciated with Hii-hi! Yiii-hi! and went off with Riua to Kirinyaga.

Now when the squirrel was coming from Kirinyaga, carrying the medicinal powder, he met Mr. Hyena who was also going to Kirinyaga to get the same powder for his own personal use. He saw the squirrel and became jealous. So Mr. Hyena assaulted the squirrel and threw the powder into the swift-flowing river. He then went back to earth.

The squirrel was worried; and so he returned back to Riua, the King, to report what Mr. Hyena had done. Then the King was angry and said: 'You squirrel, you failed in a mission entrusted to you for the people. With a curse, I charge you to remove yourself from the people and remain forever in holes in the soil. As for the hyena, he has from now on become an enemy of the people'.

The Kamba have various metaphorical phrases for death: to follow the company of one's grandfathers, to go home, to stop snoring, to be fetched or summoned, to empty out the soul, to sleep for ever and ever, to dry up, wither or evaporate, to pass away, to be called, to reject the people, to reject food, to be received or taken away, to return or go back, to terminate, to be finished or end, to have one's breath come to an end, to depart or go, to go where other people have gone, to leave, forsake or abandon, to collapse, come to ruins, to become God's property.

Akamba elder

source:http://emmanuelkariuki.hubpages.com/hub/Kamba-people-of-Kenya

http://emmanuelkariuki.hubpages.com/hub/Kamba-people-of-Kenya

Rain Making Beliefs of Akamba People

Rain making dances in Kenya vary over time and place. Akamba rituals, like rituals of any group, change over time in that new elements are added and obsolete components are removed. The Akamba are known for their use, familiarity, and knowledge of ritual traditions that are interwoven into their society.

Marilyn Silberfein provides a study of rain performances conducted to manage drought in the Kamba city of Machakos. Based on her study, the performances were directed to N’gai, the Creator and Supreme Being, and Aimu, the spirits of the departed. These spirits were invoked because of their powers to control and predict rainfall levels. The rainfall ceremonies centered on knowing when to expect rain.

In other cases, this relationship comes from old myths. Paul Kavyu shares his research on rain prophets prior to the widespread redirection of rain forecasting to the Ministry of Health. In Kavyu’s study, participants communicated with the power of “Mwathani” and higher spirits, but they never really knew if the prayers would be answered. For this reason, rain prophets, called “Athani”, were sought to conduct rain ceremonies and sacrifices.

"Two sacrifices are made for rain…When Mutitu Hill is heard roaring late at

night, or early morning hours, the already dead prophets are asking for a

sacrifice for their friends who give them the prophet’s power. This request is

made to the living Mwathani or the person concerned. After weeks after the

roaring, the person living who is concerned has to give someone alive for the

request…. The second sacrifice is made in all Mathembo in the country, to the

spirit who lives in two pools in Mutiti Hill…"

These accounts are presented primarily to show some of the older oral narratives and myths associated with rain in Ukambani. These stories and rites, although not all directly practiced, are memorialized and embedded into the culture of the people.

Droughts are viewed as catastrophic moments that require ritual intervention. The ritual process for handling poor rainfall is evident in historical records. These records indicate that the first task when faced with the threat of drought is for the community to assemble to understand the root cause of the problem. Gerhard Lindblom, in his ethnographical study, The Akamba, reported that medicine men in Ukambani were often consulted to help predict rain due to the importance of agriculture in society, which was cultivated primarily by women. Lindblom notes the following actions of female planters when there was a problem with rainfall:

"At the occurrence of a drought which threatens the harvest, the

women gather together…beating their drums they march from village

to village. Each woman who has land, must join them…’the wives

have a meeting the Akamba say."

Lindblom describes a drought intervention ceremony as an evening of dancing and singing, while the medicine man consults with the rain spirits to determine the proper actions to take. The immediate action of the community speaks to the historical practice of villagers to understand the root causes of rain instability. The lack of rain is a sign of a spiritual imbalance that the rites and interventions of the ritual dance and magic practiced by medicine men is designed to correct.

All life crises are the result of the individual or group being out of harmony with man, nature, the spirits, deities, or the ancestors; thus, a key aspect of rituals is restoring balance in a variety of situations. All rituals are conducted through the spiritual leaders, ritual specialists, or medicine workers. The highest spiritual being of the Akamba is called Mulunga, “a power of abstract conception…the creator of all things.

Over the years, rain making dance rituals have persisted in Ukambani; however, the rituals continue to adapt. Some of the older practices of women in the community, such as gathering from house to house, are no longer widespread. Instead, many of the traditional rites, like rain making, are conducted by select community members who engage in specific ritual performances. Despite this and many other modifications of the execution of rain dance rituals, what has been retained is the clear objective of the ceremony: to seek spiritual intervention that produces rain.

Rain Dance Ritual Process

There is no single rain dance ritual process since each ceremony is different and dependent on the participants, available resources, moment in time, and environmental circumstances. However, there is sufficient data on ritual structure, rain ceremonies, and field analysis to paint a narrative of the dance experience. For this study, rain dances were observed during 2008-2009 field research in Kenya. The dances were performed by a local Akamba group, Wendo Wa Kavete, from the Kibwezi District, and a local dance company in Talla, in the Kangundo District. Wendo Wa Kavete, like many others in Ukambani, are responsible for remembering and performing traditional dance ceremonies in the community. The ceremonies recorded in Kibwezi were authentic and a direct reaction to the ongoing drought there.

The rain dance transformed the community from an “unhealed” state to a “healed” state. Jean Comaroff, in her 1985 study, Body of Power, identifies several distinct ritual processes that are useful and have been modified for this analysis of rain making: summoning the spirits, strengthening, and healing.28 In addition to the phases outlined by Comaroff, based on observation of other ritual forms, there is a need for an additional phase, “celebration”. All of these phases will be analyzed in the following sections to understand the rain making dance ritual.

Summoning the Spirits

The rain making rite begins with libations and prayers. At this stage, it is clear that there are different participant roles. Unlike many rituals, the rain making ritual does not have one orchestrator. Instead, the elders, dancers, musicians, and observers all make up the ritual experience collectively, which could continue for several days.

The elders serve as the initial point of contact to the rain making spirits. Other key participants are the musicians who are trained in the precise rain making rhythms. The dancers’ bodies are the dominant symbol, and the power associated with the dancers’ movements provide the necessary energy to help invoke the spirits and healing. The community, in this ritual, is the victim; therefore, other observers in the ritual serve as the symbolic representation of the community that needs healing, while simultaneously serving as witnesses to the ceremony.

Furthermore, their presence transmits vital energy that assists the ritual. The final role is that of

the unseen rain spirit, which may or may not attend, but, as mentioned earlier, is a key force in

whether or not the community can expect future rain.

The libation acts call the spirits to receive the forthcoming rites and reveal the circumstances of the drought. This initial call varies in length and can take on many forms. Elders pouring milk libations to the ancestors to invoke the spiritual world. This commences the rain making dance ceremony. The duration of the libation is dependent upon the elder’s satisfaction that a suitable prayer and call has been initiated. As witnesses, the elders initiated libations, poured milk for the ancestors, and then drank from the calabash. They use milk, in particular, in these ceremonies because the Wakamba view milk as having the properties necessary for more blessings. During the ceremony, only men were allowed to drink the milk, showing the continuity of traditional gender roles. Despite modern pressures for the Akamba, men are still regarded as authorities and therefore leaders in important community matters.

After the opening prayer and libation, musicians began to play the drums and other instruments, creating a slow and synchronized rhythm at the same slow tempo and cycle length. The elderly female dancers are positioned in opposite areas, and they slowly move into the dance ritual space in unison. The spiritual seriousness of the ritual is seen on the faces of participants as they blow whistles and shake rattles. Dancers with their whistles and rattles during the phase in which spirits are summoned. This formation continues until a certain energy level is achieved and a spiritual line is opened.

Kamba carving

Strengthening

Strengthening is the process in which participants reach a climatic state. During this process, specific dance movements are used and referred to as kusunga or kwina, depending on the specific Ukamba territory. In addition, rain making dances utilize many symbols. In fact, the

rain making Kilumi rite is full of symbolic structure and meaning. Symbolic structure and use is

the focus of Victor Turner in his book, The Forest of Symbols:

"The symbol is the smallest unity of ritual which still retains the specific properties of

ritual behavior; it is the ultimate unity of specific structure in a ritual context…a symbol

is a thing regarded by general consent as naturally typifying or representing or recalling

something by possession of analogous qualities or by association in fact or thought…the

ritual symbol becomes a factor in social action, a positive force in an activity field. The

symbol becomes associated with human interests, purposes, ends, and means, whether

these are explicitly formulated or have to be inferred from the observed behavior."

Consistent with Turner’s description, symbols in rain making rituals are representative of an object, person, place, or thing and can be categorized as “dominant symbols” or “instrumental symbols”. The dominant symbols, according to Turner, refer to the value of the ritual or representation of non-empirical beings and powers.

The dominant symbol of the rain making ritual is the rolling of the shoulders and head locking movements through gestures of the shoulders and arms. This represents unity and the pouring down of rain. This body movement involves women bending over, locking heads with other dancers, and shaking their shoulders and arms, which, in many ways, mimics the pouring of rain. The head connections are symbolic of the interconnected nature of the environment, community, and the spirits. The locking process is also associated with an increased drum tempo that serves as the peak of this strengthening phase. The dancers and musicians are all in a transcended state, giving them power, and eventually leading to the healing of the community. Judith Hanna attempts to describe this “transcended” state in the following:

"Intense, vigorous dancing can lead to an altered state of consciousness through brain

wave frequency, adrenalin, and blood sugar changes…dance-induced altered states of

consciousness may be perceived as numinous…because motion attracts attention and

dance is cognitive and multi-sensory, dance has the unique potential of going beyond

other arts and audio-visual media in framing, prolonging, or discontinuing

communication and in creating moods, and divine manifestations."

However, it is the dancers and musicians that best articulate their experience which is more effectively communicated in their expressions. In live observations, the energy reverberates and can be felt in the resonance of the drums.

This movement is the climax of the dance, a connection with the rain spirit. The arrival of the rain spirit in the ritual is symbolic on several levels: 1) the community can expect rain and fertile crop production; 2) the eventual healing and revitalization of the community which has been afflicted; and 3) the Akamba ritual was successful and the community will be blessed. The absence of the spirit during the ritual means that the Akamba can expect hard times; this usually means the short term and symbolic death of the community.