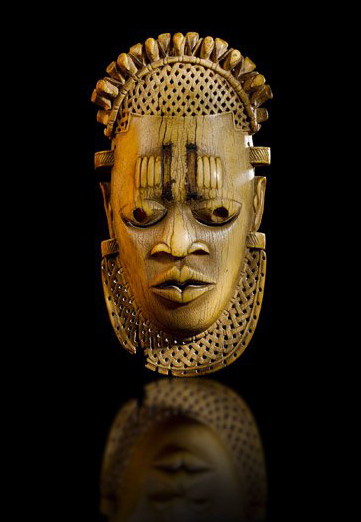

Mask: Pendant Ivory Mask of Queen Idia, the political administrator, mystical woman, warrior and the first Queen of Bini (Benin) kingdom in Nigeria

She played a very significant role in the rise and reign of her son. She was a strong warrior who fought relentlessly before and during her son’s reign as the Oba (king) of the Edo people. His son Esigie controlled Benin City while another son, Arhuaran, was based in the equally important city of Udo about twenty miles away. The ensuing civil war severely compromised Benin's status as a regional power and undermined Benin City's place at the political and cultural center of the kingdom. Exploiting this weakness, the neighboring Igala peoples sent warriors across the Benue River to wrest control of Benin's northern territories. Esigie ultimately defeated his brother and conquered the Igala, reestablishing the unity and military strength of the kingdom. His mother Idia received much of the credit for these victories as her political counsel, together with her mystical powers and medicinal knowledge, were viewed as critical elements of Esigie's success on the battlefield. To reward and honor her, Esigie created a new position within the court called the iyoba, or "Queen Mother," which gave her significant political privileges, including a separate residence with its own staff.Queen Mothers were viewed as instrumental to the protection and well-being of the oba and, by extension, the kingdom.

Idia's face was immortalized in the sixteenth century ivory mask presently in the British Museum. It became famous when the Nigerian military government chose it as the emblem for the Second Black Festival of Arts and Culture, known as FESTAC '77, that Nigerian hosted in 1977. The visibility of the mask increased when the British Museum refused to release it on loan to Nigeria even after demanding two million pounds, which the Nigerian government put up. The late Oba Akenzua II, then reigning Oba of Benin, broke the impasse by commissioning the Igbesamwan (ivory carvers guild) to produce two replicas of the Idia mask that had been looted by British soldiers of the 1897 punitive expeditionary force. The fine workmanship of the replicas established that modern Benin ivory carvers are consummate artists as were their forebears, and like the latter, responded with pride and reverence to the royal commission.

Iconic Iyoba Idia`s Festac 77 image

The exact date of birth and death of the great Iyoba Idia, the mother of Esigie, the Oba who reigned from 1504-1550 is not known. However, she was alive during the Idah war in which her army and war general secured a resounding victory for Benin (Oronsaye 1995, 61; Ebohon 1979, 60; Egharevba 1968, 28). She was a proper Edo woman from Bini (Benin) Kingdom. She was born in Ugieghudu, in the Eguae area of Isi (Oronsaye 35, 61 Egharevba 28).

The young Idia, we do know that she was “a beautiful and strong willed woman”(Oronsaye 1995, 61) whose biographical sketch reveals that she had been medicinally fortified before her marriage to the constantly warring and constantly absent Oba Ozolua. She was very clever lady who possessed skills which few people had. She matured very quickly just like other girls in that historical period were prepared early in life for their future role as wives.

Idia entered the royal household after she caught the fancy of Oba Ozolua during a dance performance in the capital (Oronsaye 61). Once the Oba initiated the marriage process, her parents knew she would become an Oba's wife and eventually took the precaution of medicinally seasoning and “cooking” their daughter for her future life. This preparation strengthened her to cope with whatever vicissitudes palace life would throw at her. The “strong willed” Idia and her parents would have surmised that life as an Oba's wife may be tumultuous, but was indeed an excellent route to power and wealth. It would have made sense for them to take advantage of all the excellent opportunities it offered to advance their Ugieghudu family and Idia's own personal line.

As an oloi (royal wife) of the Oba, Idia became very powerful at the court in her early marriage. Constant references to her occult powers in oral accounts suggest, not that she was being used by male palace chiefs, but that by virtue of these powers, she was reasonably well connected with all the key players and powerful figures in Oba Ozolua's erie (royal wives residence). It is not inconceivable that she may have had excellent relations with the Uwangue and Osodin, and other palace officials some of whom or their mothers' may have come from her Ise district.

According to an article on http://www.edoworld.net entitled "Iyoba Idia: The Hidden Oba of Benin restoring agency to a sixteenth-century oloi, royal wife, is crucial since it enables us to reevaluate contemporary rationalizations that are used to portray women, and such a woman in particular as passive objects of exchange. One of such rationalizations is the explanation offered about the marks on Idia's forehead. What today is being described as a failed attempt to prevent her marriage to the Oba masks the sixteenth-century social scheme in which the Oba was the most powerful figure in that universe; and in which it makes no sense for any girl or her parents to rebuff his marital overtures. Second, this concealment of the social scheme enables twentieth-century chroniclers to hide that Idia's supernatural powers and medicinal knowledge were enhanced through initiation; hence ensuring that this act of Idia was not emulated by contemporary oloi. Thirdly, the fact of initiation establishes why we should not hastily write off Idia as an ignorant slip of a girl who was politically clueless and unprepared for palace intrigues. The initiation reveals a family's politically ambitious response to the Oba's interest in marriage, and to a daughter schooled in the science of esoteric laws. Yes, Idia's family would have been thankful that their daughter's ehi (guardian spirit or destiny) dealt her a good hand but it was up to them to ensure that she stood out from the countless other iloi amassed in the erie (royal wives' residence)."

Commemorative head of a Queen Mother From Benin, Nigeria, early 16th century AD

Oloi Idia gave birth to her first son, Osawe (Oba Esigie) to Oba Ozolua. Prince Osawe was the third born son of Ozolua. The first son of Oba Ozolua was Ogidogbo and the second son was Aruanran (sometimes spelled Arhuanran), the son of Oloi Ohonmi who was born earlier in the day before Esigie. Yet, Esigie's birth was officially announced to the Oba before Ohonmi's son enabling him to claim second place. According to Edo oral history "because Idubor did not immediately cry at birth, Osawe who did, was reported first to the king, according to tradition. By the time Idubor cried, to enable the mother report his birth, the king had performed the proclamation rites of Osawe as first son." Despite this glaring fact, some critics of Iyoba Idia suspect she has a hand in her son Esigie's path to power by alluding to usurpations of the principle of primogeniture in which Idia was the central actor and beneficiary. "To switch the order of births in the royal palace in order to bring herself closer to power was no mean feat. It required political savvy, extensive political connections, phenomenal co-ordinations, and deep collusion with a network of critical actors—women ritual specialists in the palace, the Okaerie who trains the new iloi (royal wives' residence), the Eson or first wife whose duty is to manage the erie (palace), titled wives, the Ibiwe and other key palace chiefs such as the Uwangue and Osodin who looked after royal wives and their children, and cared for them when they were pregnant."

When Oba Ozolua died in 1504, the Bini Kingdom was unleashed with a vicious struggle for power between his two eldest sons, the warrior giant Aruanran and the Portuguese-baptized Osawe—Esigie's personal name (Egharevba 26). The fight ensued between Osawe and Aruanran only because the first son of Oba Ozolua, Ogidogbo, lost his obaship rights. He had fractured his leg in a competition with his two younger brothers, Aruanran and Esigie, and became a cripple (Egharevba 25). Although this tragedy was represented as an unfortunate mishap, a case of children competing against each other, many at the time saw Idia's hand behind it. For them, this surreptitious mode of altering physical reality from a supra physical level represents Idia's mode of fighting on two planes. It also signified her double-edged sword that could both create or wreak havoc.

Idia's role in the nullification of the first son Ogidogbo was not lost on Aruanran whose enmity towards his brother (Esigie) intensified that he tried to assassinate him. A noted warrior and conqueror of the fierce town of Okhumwu, Aruanran was bigger and stronger, and could easily have trounced the weaker Esigie, whom Oba Ozolua had sent to attend the Portuguese mission school after his baptism (Ryder 1969, 50). Aruanran's assassination attempts could have succeeded were it not for Idia who was reputedly skilled in magical arts and whom he knew was a formidable opponent he had to overcome. Realizing he had to acquire supernatural powers if he wanted to take on Idia who was her son's spiritual protector, oral tradition recounts that Aruanran retreated to Uroho village to learn the art of black magic from an old sorceress, Iyenuroho (Okpewho 1997, 21; Egharevba 25). That he chose a woman as teacher is clear recognition that his opponent was a woman, and that he had to learn the ways of women's mystical powers to be assured of victory. We should note that it was Esigie's possible lack of combat experience, the result of having to attend the school of Portugese missionaries, rather that join his father in fighting wars, that explains why Idia had to lead an army to war to ensure that Benin soldiers fought valiantly against the Idah army.

Refusing to accept defeat, who was also the Duke (Enogie) of Udo, Idubor Aruanran refused to accept subordinate role to his brother, Oba Esigie, and at first tried to make Udo the capital of Benin kingdom with himself as king. It did not take too long before the two brothers went to war. The war was difficult, bitter, and long drawn out. It was not until the third campaign that Udo was defeated. The third campaign was timed to coincide with the planting season when Udo citizen-soldiers, who were mainly farmers, would be busy on their farms. The Enogie´s only son, Oni-Oni, died in the battles. Even after that defeat, Udo´s Iyase and commander of their troops, returned to the offensive and after his defeat, the people of Udo escaped to found Ondo town deep in Yoruba territory.

Iyoba Idia`s bronze Sculpture

The Enogie of Udo committed suicide by drowning at the Udo lake after his defeat. He did not want to be captured prisoner and taken back to Benin. Before jumping into the lake, he left his ´Ivie necklace,´ the precious bead necklace symbol of authority in Benin land, dangling from a tree branch were it could be easily found. Only the Oba could inherit such trophies of dead or conquered leaders and nobles, so, out of excitement over his victory, he tried on his neck for size, his brother´s humble surrender necklace symbol. He became mentally disoriented immediately he put the necklace on his neck. Removing the necklace from his neck did not make any difference, so he was rushed back to Benin City in that hopeless state.

His mother, Idia, immediately located a Yoruba Babalawo (mystic) at Ugbo/Ilaje, in the riverine area, and brought him to Benin to work on the king´s spiritual ailment. He cured the Oba of his ailment, and the Queen after rewarding him generously, prevailed on him, (the Yoruba Awo), to settle permanently in Benin to continue to render his services. He set up home at Ogbelaka quarters where his descendants have thrived until this day.

With Aruanran`s death and his son cured of his deranged ailment, Idia put her talents into the administration and protection of his son`s kingdom. She became a noted administrator and a great Amazon and an influence on her son, Oba Esigie. His son recognizing her role introduced a special post in the administration for his mother called the Iyoba, the Queen Mother. She was personally involved in many of the wars of conquest by the Oba and even led some of them herself. A Dutch chronicler would report a century later that the Oba "undertakes nothing of importance without having sought her counsel". The art of the time reflects this reality. Esigie commissioned a highly improved metal art that has since achieved worldwide distinction. Of the best-known pieces are the famous Queen Mother Idia busts. Professor Felix von Luschan, a former official of the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde, stated that: "These works from Benin are equal to the very finest examples of European casting technique. Benvenuto Cellini could not have cast them better, nor could anyone else before or after him … Technically, these bronzes represent the very highest possible achievement."

Queen Mothers were therefore viewed as instrumental to the protection and well-being of the oba and, by extension, the kingdom. Indeed, obas wore carved ivory pendant masks representing the iyoba during ceremonies designed to rid the kingdom of malevolent spiritual forces. An especially fine example of such masks in the Metropolitan Museum's collection dates from the sixteenth century and is believed to depict Idia herself (. Two vertical bars of inlaid iron between the eyes allude to medicine-filled incisions that were one source of Idia's metaphysical power.

Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba, 16th century

Nigeria; Edo peoples, court of Benin

Ivory, iron, copper (?); H. 9 3/8 in. (23.8 cm)

The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972

(Among the most celebrated masterpieces of African art, this pendant is at once a prestige object worn by the king on ceremonial occasions and the portrait of an important historical figure at the court of Benin. The preciousness of the material and the refinement of the carving indicate that it was created by the exclusive guild of royal ivory carvers for the king.

Framed by an elegant tiara-like coiffure and openwork collar, this likeness of an Edo royal woman is in fact a portrait of Idia, mother and close advisor to one of Benin's greatest leaders, Esigie, who ruled in the early sixteenth century. Esigie honored Idia for helping to secure his claim to the throne and for the wise counsel that she provided him throughout his reign. As a consequence of Idia's role, the title of Queen Mother (Iyoba) was introduced to the Benin court, granting the mother of the oba (king) equal authority to that of senior town chiefs.

The miniature motifs of Portuguese faces depicted along the summit make reference to the extraordinary wealth generated in the Benin kingdom in the sixteenth century through trade with the Portuguese. Since the Portuguese arrived by sea, generated local wealth, and have white skin, they were immediately connected to Olokun, god of the sea, who is associated with the color white. Additionally, Olokun is linked to purity, the world of the dead, and fertility. The mudfish motif, which alternates with the Portuguese faces, is one of the primary symbols of Benin kingship. It is associated with the qualities of aggressiveness and liminality due to its ferocious electric sting and its ability to survive in water and on land.

The hollowed back of this work suggests that it was both a pendant and a receptacle, possibly containing medicines to protect the king while worn during ceremonial occasions.

Given the scale of this artifact and the inclusion of suspension lugs above and below the ears, it appears likely that it was worn suspended as a pectoral. Recent ritual practices, however, suggest that related works may alternatively have been worn at the king’s waist.)

Altar to the Hand (Ikegobo), late 18th century

Nigeria; Edo peoples, court of Benin

Bronze; H. 8 1/4 in. (20.96 cm)

(The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.218)

In the royal kingdom of Benin, cylindrical "altars to the hand," or ikegobo, are created to celebrate a person's accomplishments and successes. Ikegobo are dedicated to the hand, the aspect of an individual's being associated with action and the initiation of change which is at the root of one's achievements. Depending on a patron's wealth and place within the hierarchy of the kingdom, these objects are made of brass, wood, or clay.

This cast brass ikegobo was created for an iyoba, the mother of the king. Because of her position, the queen mother enjoyed many of the privileges accorded to high-ranking men, including the right to commission personal and ritual objects from brass, a costly material strictly regulated by the king. As in other examples of Benin royal sculpture, scale and courtly regalia are used to denote rank and importance. The iyoba is recognized immediately by her size and the full complement of coral bead accoutrements associated with her position: the distinctive peaked crown, high collar, netted shirt, and crossed bandoliers. She is flanked by two female fan-bearers who support her arms, a position also assumed by the king when appearing in state. Two other female attendants carry containers, perhaps holding items of tribute, above their heads. Beyond them a pair of male servants, clad in cloth wrappers, hold staffs. The seven figures are superimposed onto a background of alternating bands patterned with floral, braid, and interlace designs. An opening at the top of the altar receives a carved ivory tusk. Their relative nudity and distinctive crested hairstyles identify the female attendants as women specially raised in the palace by the iyoba herself. These women, highly respected for their refinement and education, will become the wives of the king or may be given in marriage to cement political alliances with important chiefs.)

These attendants, also depicted in carved ivory (1978.412.302), were women under the tutelage of the iyoba destined for marriage to her son, the future oba. As with ancestral obas, deceased iyobas were venerated with cast brass memorial heads (1977.187.36) fitted with carved ivory tusks and displayed on royal altars.

Idia`s Mystical Prowess

A knowledgeable person is a reflective being. Idia's successful entrance into the royal palace meant that she came with an elevated consciousness that situated her in an empowered, knowledgeable position. African religion scholar, Jacob Olupona, explains that in early African cultures, the “ability to display magical prowess and medicinal knowledge . . . were viewed as signs of bravery and valor when channeled towards the benefit of the community”(1991, 29). Bradbury reinforces this point when he contends that “the sanctity of the king's authority lay in acceptance of his ability to control those mysterious forces on which the vitality of [Benin] society depended (1973, 75). These explanations remind us of other ways power is conceptualized in certain cultures and in different historical times. Where today economic power is the route to political power, in old Benin, magical prowess was a well trodden path to political power and riches. The case of Okpota, the famed Ishan ritual specialist and doctor in Oba Ozolua's court is a case in point (Egharevba 24). Power is not always conceptualized in physical terms to be used and forcefully applied over others. Supernatural power is preferred, revered and feared because of the mysterious way in which it works. Insubstantial, unseen, and hidden, only a ritual specialist who understands its operative principles can manipulate physical and material reality to produce desired effects.

Queen Idia, mother of Oba Esigie, king of Benin from the late fifteenth to the early sixteenth century, played a key role in her son's military campaigns ..

Possession of supernatural knowledge bestows power, because one becomes an unseen causal agent. Possession of this power is not determined by gender but on how psychically strong one is. Herbalists, doctors, ritual specialists, and priests were not all men in Oba Ozolua's time as the case of his oloi, Enaben, “a great sorceress” attests (Egharevba 24). Women ritual specialists and priestesses were as powerful as their male peers, if not more powerful, which is perhaps why they were the one who had the onerous task of psychically protecting the Oba against witchcraft. Centering African experience allows us to see that the force of an Oba's supernatural powers was politically crucial for “the multitudinous ritual functionaries who were directly beholden to him, and by the chiefs whose authority, in the eyes of the people, derived from him” (Bradbury 1973, 75). It also allows us to integrate this category of magical prowess into our interpretive framework even if it disrupts the dominant empiricist framework of scholarship that dismisses anything metaphysical or supernatural as nonsensical. Acknowledging that possession of esoteric knowledge was important in the social and political universes of ancient Benin, enables us to understand Esigie's investment in Idia's prowess since the supernatural arena is the realm in which real power resides.

For the sixteenth century historical period, the ability to display magical powers was crucial and was tied to political survival. The greatness of Oba Ewuare was substantially based on his reputed skill as a magician and doctor as well as on his skills as a warrior. Ozolua's reign as a warrior-Oba was consolidated and extended with the help of ritual specialists including Okpota. The same was required of Oba Esigie when he needed to gain control of the throne and win the Idah war. In order to firmly assert his authority in the kingdom so soon after his accession, he had to be an adept manipulator of mysterious supernatural forces, or he needed to be seen as having the resources to do so. Idia provided this invaluable component to his reign, knowing his limitations in this area and knowing that ferocious hostile forces were arraigned against him. Her charms, magical prowess, and supernatural powers were deployed for the administration of Benin empire.

Idia came to the palace fortified with her medicinal knowledge and magical powers as her war dress for the 1515-16 battle indicated. According to the royal bards, on her head was a distinctive coral war crown peculiar to her alone. Resting on her forehead was “ugbe na beghe ode, eirhu’ omwan aro,” a charm with four cowries that ensured any oncoming stone or missile will not blind her. On the back of her head was “iyeke ebe z’ukpe,” the charm known as boomerang. On her neck was “iri okina” (precaution rope) with four leopard teeth tied to it. The rope reminded her to be careful and to avoid danger. On her chest was “ukugbavan” (a day belt) designed to ensure that whatever the nature of the problem dawn will always come. Hidden under it was “uugba igheghan odin,” the belt of dumb bells used to hypnotize her enemies while her “ukugba igheghan” (the belt of bells) jingled to frighten enemies.

Queen Idia s Mask Nigeria s gift to UNESCO

Head of a Queen Mother (Iyoba), 1750–1800

Nigeria; Edo peoples, court of Benin

Brass; H. 16 3/4 in. (42.54 cm)

Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1977 (1977.187.36)

(In the Benin kingdom, the iyoba, or mother of the oba (king), occupies an important and historically significant place within Benin's political hierarchy. The title was first conferred upon Idia, the mother of king Esigie, who used her political skill and supernatural abilities to save her son's kingdom from dissolution in the late fifteenth century. Ever since that time, queen mothers have been considered powerful protectors of their sons and, by extension, the kingdom itself. Because of the enormous esteem in which they are held, iyobas enjoy privileges second only to the oba himself, such as a separate palace, a retinue of female attendants, and the right to commission cast brass sculptures for religious or personal use.

Ancestral altars dedicated to past iyobas, like those of past kings, are furnished with cast brass commemorative heads. The heads of queen mothers are distinguished from those of kings by the forward-pointing peaks of their coral-beaded crowns. Commemorative heads of iyobas hold to the same stylistic chronology as those of obas. Earlier heads were cast with thinner walls and display tight beaded collars that fit snugly beneath the chin. Later versions have thicker walls, exhibit enlarged cylindrical collars that cover the face up to the lower lip, and are designed with a circular opening behind the peak of the crown to hold a carved ivory tusk. This head of an iyoba dates from the eighteenth century. While its high collar and pierced crown place it with later examples, the sensitive, naturalistic modeling of the face is reminiscent of the earliest commemorative heads.)

Idia's outfit and entourage would evoke the scene of standard sixteenth century war bronzes since sexuality is ambiguously rendered in Benin art. It is crucial to make this point to underscore that it would be difficult for present-day viewers to easily differentiate between male or female personages in battle gear in royal plaques. Because sexuality in Benin artistic practice prior to the twentieth centry was muted, Western and twentieth century Nigerian assertions that figures in sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Bini plaques were male are typically based on assumptions and hypothesizations of male dominance in history. Yet, in the depiction of important historical events, the Igbesamwan and Iguneromwon of the period were not concerned about anatomical sex as they were about projecting the power, pomp and awesomeness of the personage. With this information as a backdrop, we have to recognize that since the customary mode of dressing for both men and women in the aforementioned historical period were wrappers, this would make the battle dress of a male general indistinguishable from a female general.

British soldier with the looted artifacts of Benin Kingdom including that of Queen Idia

Iyoba Idia went to war as Iyoba and a general; not as a woman! The medicinally fortified belts and sashes she, like other generals, wore for protection would be the focal point of interest for the Igbesamwan and Iguneromwon, not her breasts, which like that of other male generals, would have been covered by the range of accoutrements, belts and sashes they all wore. It bears restating that there is a crucial difference between Western and Benin artistic frameworks. Unlike standard European artists and sculptors who created in a hyper-sexual infused framework, the artictic concern of the Igbesamwan and Iguneromwon was not sexual titillation, breast objectification, or realistic anatomical representation. They sculpted in broad strokes depicting concepts, symbols, official roles, and cryptic historical scenes. Prior to Idia's invention of the Iyoba's parrot beak coral hat, she would have had to wear a coronet of coral beads and coral bead shirt that signifies her royal status (Bradbury 1961, 129). Thus, in battle, her outfit would have resembled that of an oba, and artistic focus would have been placed on the office and the warrior, not on the female body.

As the grand protector of the kingdom, Idia's powers were particularly crucial during the major military challenge Esigie faced as a new Oba. The Idah army was on its way to the capital. The fratricidal accession battles had left behind a fragmented army and dispirited Bini soldiers. Matters were not helped when the ibis, conceived as a bird of prophesy, flew over the soldiers marching to battle shrieking and flapping its wings. The rattled royal diviners predicted military disaster and urged retreat, but resolute Idia drew upon her strength and reputation in supernatural powers and neutralized their prediction of doom. Closely heeding the counsel of his mother who was on the battlefield with her own army, Esigie (probably Idia) ordered the bird to be shot. Fortified by her powerful presence, and at her urging, Esigie rallied his dispirited soldiers to a victorious battle. Idia's role here is not unlike the role of the Omu (female monarch) of Aboh whose magical shield and war canoe always led Aboh soldiers to war, and without which they would not fight (Ekejiuba 1992, 102-03; Nzimiro 1972).

Ritual knowledge was extremely important in sixteenth-century Benin political administration as well. An Oba was supposedly divine, and the stability of the empire depended on his spiritual strength and power for which a vast array of rituals were performed. Against this background of the importance of magical prowess, we begin to grasp the importance of Idia to Esigie's political administration. Lacking those sorts of powers himself, he entrusted his mother to supernaturally protect him. He trusted her completely, knowing that she was his main ally and that she would not betray him. He relied on Idia's metaphysical powers to clear away all psychic and physical obstacles and impediments, which presumably freed him to attend to other matters within his area of competence. The information Idia gained from her visionary insight and supernatural powers enabled her to offer better political counsel, to amplify his omniscience and omnipotent qualities, to enhance the awesomeness of his divinity, and to make his reign much more outstanding. Where his warrior father, Oba Ozolua was unsure about trade with the Portuguese, Esigie, the political strategist, was comfortable with expanding Benin's trade with the Portuguese having been taught by them. He confidently defined the terms of external trade to suit Benin's national and imperial objectives, rebuffing Portuguese demands for slaves, by limiting its export (Ryder 1969, 45). Sargent contends that this embargo on slave export, the result of deep psychic insight and a long-ranged vision, “was striking evidence of Benin's paramount concern for legitimate commerce and elite exploitation of the legitimate aspects of east-west , north-south, and European coastal trade potential” (1986, 418).

Contemporary theorists and scholars continually understate the importance of testimonies from Benin oral tradition that speak about Idia's supernatural powers. We rarely accord them the requisite weight they deserve and the impact they had in political affairs of the time. Working within an empiricist framework of knowledge, we fail to appreciate that these were crucial powers for holders of any political office, and that Idia's possession of them gave her superordinate rights and allowed her to participate in political decision making. We know that Esigie did not possess this power and, while he had royal diviners, priests and priestesses who attended to spiritual matters, he leaned heavily on his mother. He relied on her to cross-check the veracity and accuracy of their spiritual recommendations as she had done in the field of battle. Even in present-day Benin, Idia's possession of these powers are celebrated, indicating that every Bini indigene knew that she used it for political affairs for the enhancement and glory of Benin. Remarkably, in spite of the modern gender ideology in place in contemporary Benin, current day Binis still understand and appreciate that this is why Idia was such an important factor in Oba Esigie's reign. An appreciation of this point by theorists and scholars of Benin is crucial for understanding why it is misguided to frame Idia's through a western framework that exclusively construes women as wives, and that envisions them as nonthreatening and apolitical, and structurally relegates them to a subsidiary position

Iyoba Idia`s conceptualization

Contemporary evaluations of Iyoba Idia tend to underscore her role as royal wife (and mother). Kaplan contends that an Iyoba's power was rooted in her success in childbearing, in bringing forth the reigning Oba, and in ensuring the continuity of the family and the state. In other words, it is because Idia fulfilled her roles as wife and mother that Esigie created the title of Iyoba to honor and reward her in her lifetime so she will remembered thereafter (Kaplan 1997, 59). If this is true, then this office of Mother of Oba should have been created not for Idia, but for Erinmwide, daughter of Osanego, the ninth Onogie of Ego, and mother of the very first Benin oba, Oba Eweka I. She was more deserving of the title for she is the Edo anchor of the Eweka dynasty. The fact that this was not done for Erinmwide, or in her name, or for previous iye obas (mother of Obas) indicates that maternity per se was not the rationale or basis for the creation of the office of Iyoba.

This qualification does not mean that motherhood is unimportant or disconnected from the office. Rather, what it states is that we have to make a clear distinction between the political office of Iyoba and the material fact of being an iye oba or Oba's mother. The distinction may seem unimportant since the occupant of the office is the Oba's mother. Indeed, the convergence of the two states makes it difficult to separate the political institution; but there is a radical difference that the focus on being a mother obscures. The creation of the Iyoba title was compelled by sociopolitical conditions of the time which will be explored latter. As a political office with a court, chiefs, and retinue, the office of Iyoba was a political experiment that constitutionally modified the previous or old political system. This modification created and made provisions for the category of Supreme Motherhood, in which the occupant of the office functions as the Mother of the Nation. The political powers that were vested in this office were not parallel to that of the Oba, who created it, or equal to the Oba's power. Because the moral and social authority of a mother supersedes that of her offspring, the moral, social, and spiritual powers of Iyoba superseded that of the Oba because the Omo (child) is subordinate to the parent. Thus, if the Oba was the spiritual embodiment of Edo people, the Oba n'Osa (An Oba who is god to his subjects), and the Uku Akpolokpolo (The mighty one that rules) of Benin, the Iyoba was Iy'Oba n'Osa (The Mother of the Oba who is god to his subjects). Note that on this scheme no father exists!

Queen Idia

The office of Iyoba defines a position of supreme moral authority and power. Officially, the occupant of the office was the Supreme Mother of the nation as well as the political mother of the Oba. While she supersedes him by virtue of her womb and maternal role, she does not need to threaten nor undermine his political powers. Rather she shores it up, strengthens it, and functions as his strong political and moral center while guaranteeing his safety in the turbulent politics of the kingdom. For all this to work constitutionally, an iye oba's maternity has to be transformed and radically reconstituted at the supranational level so that the occupant is no longer an individual with a personal history. This transmutation is required because the individual to whom she was his mother no longer exists. He has ritually died, and been reborn in a divine state as Oba, and exists as the soul of the nation. The political accession of an Oba paves his way into divinity, and his mother, if alive, would equally undergo a similar transformation to continue the task of nurturing the soul of the nation. Thus, on accession to office, an Iyoba metamorphoses into a boundless fluid state in which she assumes, embodies, and becomes the collective histories of past occupants of the office as well as of the spiritual mother of the Oba and all Edo people. Creating the office of Iyoba, may be Idia's and Esigie's way of constitutionally enshrining and centering Erinmwide or the Edo component in the making of the second dynasty. Whatever the implications, the office was created on the basis of the qualities Idia brought to government.

Although located within a western epistemological framework and she used the term “queen mother,” Barbara Blackmun's portrayal of Idia is closer to the historical figure because she stresses the skill and knowledge resource that Idia brought to office (1991). She acknowledges Idia's status as a mother without circumscribing her potentialities; she correctly explains that the most admired feature of Idia is her knowledge of the occult; but she does not explore the political implications of the concept of Iyoba and the Iyoba's office for the kingdom of Benin. Although Blackmun is aware that being knowledgeable in the occult may define a woman as a witch, she is quick to note that it is not considered evil in a responsible woman like Idia. The relevance of this observation is that it shifts the basis of Idia's power from procreation to knowledge possession, and to the type of knowledge she brought to Esigie's administration. A study of these show that she was feared and that her political opinions, pronouncements, or acts, were respected. The areas where Blackmun's analysis runs into difficulties, in her review of the “Queen Mother tusks of Set IV,” is when she slid into the western gender framework and failed to see that those tusks may actually be stating a radical fact about the political institution of Iyoba and that some Iyobas may actually have ruled for their sons (1991, 61)

Altar Tableau: Queen Mother and Attendants, 18th century

Nigeria; Edo peoples, court of Benin

Brass; H. 13 1/2 in. (34.29 cm)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klaus G. Perls, 1991 (1991.17.111)

(This cast brass tableau, or urhoto, was originally displayed on an ancestral altar dedicated to the mother of a ruler of the Benin kingdom. The queen mother, or iyoba, occupies an important place within the political hierarchy of the Benin court. By protecting the health and well-being of her son, she helps to safeguard the security and prosperity of the entire kingdom. In light of her position, she is entitled to certain prerogatives enjoyed by high-ranking male titleholders, such as a luxurious palace, a coterie of attendants, and the right to commission sculpture in ivory and brass. After her death, a large altar dedicated to her memory is constructed within the palace and decorated with an assemblage of sculptures that celebrate her achievements and facilitate communication with her spirit in the afterlife.

This urhoto is composed of nine figures upon a rectangular base with a square opening at the center. Motifs referring to her strength and achievements such as mudfish and elephant trunks with hands holding leaves, and those of sacrificial offerings in the form of goat and ram heads, appear on the sides of the base superimposed over an interlace pattern. Above, the iyoba is shown surrounded by a group of eight female servants. Similar to other examples of royal art from Benin, the iyoba's superior rank is communicated through her greater scale and the detailed depiction of coral bead regalia. She wears the peaked crown traditionally associated with her position, as well as a cylindrical collar, netted shirt, and crossed bandoliers worn by high-ranking chiefs. The female attendants who surround the iyoba carry insignia of the iyoba's importance, including circular fans and a sword and staff of authority. Two young women stand on either side of the queen mother to support her arms, an arrangement also assumed by the king when appearing in state. Behind her, a pair of attendants hold shields above her head to protect her from the sun.

The unique crested hairstyle and abundant coral ornaments found on the attendants mark them as women destined for marriage to the king or other major political figures. Raised in the palace by the iyoba herself, their sophistication and education make them valuable partners for powerful courtiers.)

The FESTAC Mask

Iyoba Idia's visage is the most widely known face of an African royal woman after the Egyptian Queen, Ahmose-Nefertari or Nefertiti. Her face has gazed on us from countless museum pedestals the world over. It has been widely reproduced on commemorative trays, cups and plates, jewelry, ebony and brass plaques, and on textiles, specifically george materials of the Intorica and Indian Madras labels, wax design cotton prints, and tee-shirts.7 Idia's face was immortalized in the sixteenth century ivory mask presently in the British Museum. It became famous when the Nigerian military government chose it as the emblem for the Second Black Festival of Arts and Culture, known as FESTAC '77, that Nigerian hosted in 1977. The visibility of the mask increased when the British Museum refused to release it on loan to Nigeria even after demanding two million pounds, which the Nigerian government put up. The late Oba Akenzua II, then reigning Oba of Benin, broke the impasse by commissioning the Igbesamwan (ivory carvers guild) to produce two replicas of the Idia mask that had been looted by British soldiers of the 1897 punitive expeditionary force. The fine workmanship of the replicas established that modern Benin ivory carvers are consummate artists as were their forebears, and like the latter, responded with pride and reverence to the royal commission.

It is unclear if the Nigerian military government officials who approved the mask as the symbol of FESTAC 77 would have done so if they knew the face was that of a woman. There was a time scholars such as George Parrinder declared that the face belonged to an Oba (1967, 108). Flora Edouwaye S. Kaplan explains that these kinds of interpretations were proffered because the Iyoba's “sexuality is muted and rendered ambiguous in [Benin] art” (Kaplan 1997, 89; 1993, 55). While this may be true, the perception that these ivory masks depicted Obas' also stem from two misguided assumptions: one is the European artistic convention of how females and female bodies should be rendered in art; and the second is the view of old Benin as “a society suffused with strong male ethos” (Kaplan 1993, 63) in which women did not command any power. The result of these two misconceptions is that figures that may have been female are described as male.

The identified Idia mask in the British museum, for which replicas were carved, is one of several such ivory masks commemorating Iyoba Idia looted by British soldiers after the 1896 Benin Expedition. These ivory masks were carved as memorials to Iyoba Idia after her death together with the cast copper alloy Uhunmwun Elao (or ancestral heads) that Oba Esigie commissioned the Iguneromwon (brass casters guild) to produce for his mother's altar. These ivory face masks were typically carved with a chisel and file without any models or design. They are part of a collection of pendant plaques that Benin Obas' wear around the waist during the annual Igue festival to strengthen the Oba and the Emobo ceremony that commemorates Esigie's defeat of his brother, Aruanran. These belt pendant plaques were produced in the same historical period that the Igbesamwan was carving fine, intricately carved ivory tusks, saltcellars, daggers, and spoon for the Portuguese market (Bassani and Fagg 1988).

As the illustration shows, that these ivory masks were meticulously carved with ornate designs that reflect the dignity of Iyoba Idia. Through their workmanship and designs, the Igbesamwan as well as the Iguneromwon visually celebrated Esigie's reign as a period of expanded trade and diplomatic contacts with Portugal. They produced ivory sculptures and cast copper alloy works whose motifs of leopards, oba, warriors, Portuguese mustekeers, traders, Ohensa priests, mudfish forms, ibis (ahianmwen-oro or “bird of prophecy,” sometimes referred to in older texts as vulturine eagles), horses, ukh urhe (rattle staff), mirrors, and eben (ceremonial sword of state) spoke to the power, prestige and splendor of the times. The tiara of the mask in the British Museum (as well as a similar mask in the Metropolitan Museum New York) displays exquisitely carved miniature heads of Portuguese soldiers. These frame the crest of the Iyoba's lattice-work, coral beaded cap. An intricate border frames the lower part of her face, made up of alternating images of Portuguese merchants and of deep ocean fish and heads, symbol of the god Olokun as well as the royal symbol of ocean-derived wealth and riches (Bassani and Fagg 154). By contrast, the equally exquisitely sculpted ivory mask in Linden Museum, Stuttgart is framed with fine, intricately carved miniature forms of deep ocean fishes. Like the fish design, the stylized Portuguese heads are integral to the overall design of this ivory pendant mask, and like the former, they proclaim the power, pomp and pageantry of Iyoba Idia, and the formidable presence of the then newly created Iyoba title in Benin political affairs.

Standing Female Figure, 18th century

Nigeria; Edo peoples, court of Benin

Ivory, metal; H. 13 in. (33.02 cm)

The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1972 (1978.412.302)

(This young female figure represents an attendant of the iyoba, or mother of the king. The queen mother cared for young women who served at her court until they reached marriageable age. At that time, her son, the oba, could marry them or give them to important chiefs to cement political alliances. Traditionally, these ladies-in-waiting wore scant clothing during their service under the iyoba, except for elaborate ornaments made from coral beads such as the crested headdress, necklace, belt, bracelets, and anklets displayed here.

The figure's stocky proportions and the interlace pattern carved on the base are typical of ivory works made in Benin. Beginning in the eighteenth century, ivory was increasingly used for royal sculpture. Trade in ivory with Europeans had brought increased wealth and prestige to the kingdom and this prosperous trade relationship was evoked through courtly objects made from this precious local resource. As with other comparable materials such as brass and coral, the use of ivory was tightly regulated. The right to commission ivory objects was limited to high-ranking members of the court, and a special guild of craftsmen employed by the king were the sole artisans authorized to create items from this material.)

A testimony of the enduring power of Idia's political influence is that a replica of this mask continues to be worn by a reigning Oba during the main annual rededication ceremonies. Oba Erediauwa confirmed that of the two strings of ivory pendants he wears during the Igue festival and for the Emobo ceremony, one is the ivory pendant of the face of the Iyoba (Kaplan 1997, 93). The fact that the spirit of Idia, expressed through this pendant, still looms large over contemporary royal rites, leads us to ask, what really was Iyoba Idia's true role in Benin political organization, and what exactly was the nature of her relationship to Oba Esigie.

source:http://www.edoworld.net/IYOBA%20IDIA%20THE%20HIDDEN%20OBA%20OF%20BENIN.htm

10 things you must know about “Idia n’Iye Esigie” of a West African civilization - The Benin Empire

By Uwagboe Ogieva

Idia – ( Aproximately 1484 – 1540)

Popularly know as “Idia ne Iye Esigie” was the …

First Woman to earn a title from the Empire as “IYOBA” also represented as “The Queen mother”

First Woman to have stopped the killing of the King’s mother at the ascension of kingship throne in the history of Great Benin – West African Civilization

First Woman commander [mother of the king] to have led soldiers/warrior to fight and win a war in defense of her Nation.

First Woman [mother] to have produced a one of most enlightened prince(Son) relating with the Europeans in their early encounter.

First woman to have witness one of the highest diplomatic ties btw Black Africa and Europeans [Portuguese] in her time, say about 1484 – 1540.

First woman to have witness the early formation of churches and missionary school in Nigeria.

First Woman to have lived one of the most fearful and dreadful time of continues war both in the husband’s reign [Ozolua] and her son’s reign [Esigie].

First woman to have taken up the mantle of leadership in terms of socio – economic development of the Old Benin Empire, which was invaded and burnt down by the British military force 1897 during the British – Benin War in Nigeria

First woman to have introduce the gladiators spirit and high virtues of feminism in the history of Black African civilization

First Woman to have earn world class recognition, respect and dignity, of whose presence [sculpture and art work] continue to show in every media and publications far and near. Same woman, the face of the popular Ivory Mask.

source:http://ihuanedo.ning.com/profiles/blogs/greatness-of-an-african-queen-mother-idia

0 comments:

Post a Comment