The tough guerrilla fighter with a trademark long Rastafarian hairstyle was the leader of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army and self-proclaimed President of Kenya. His guerrilla warfare activities put excruciating pain and constant fear in the British land grabbers that imposed their rule in Kenya. He was feared in equal measure by friends and enemies alike, as he does not forgive people who betray the cause of Mau Mau fight against the British.

Dedan Kimathi, Kenyan political leader and freedom fighter who led the fight for independence from Britain

Kimathi gained the status of revolutionary and martyr to the cause of black liberation in Kenya when he was was shot and captured in the forests near Nyeri. Clad in a leopard skin and carrying a .38 revolver, Kimathi was charged with carrying a lethal weapon –a capital offence under the emergency regulations then governing Kenya. He was sentenced to death and hanged at Kamiti prison on 18th February 1957.

Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi`s conspirators showing the leopard skin he was fond of wearing. He was caught after six months of hunting in the jungles of Kenya.

A highly controversial character, Kimathi's life has been subject to intense propaganda by both the British government who saw him as a terrorist. He was accused of being an unpleasant and dangerous cult leader who represented a reversionist, primal and unspeakably savage baring of the African soul. He was accused by the British of killing the settler white farmers and their African collaborators; as a result he was tagged as a terrorist by The British Nairobi government and a price tag of £500 was put on his head. In one of their propaganda Ian Henderson, the man who lead the British man-hunt of Kimathi said "Nobody has helped the government as much as Kimathi, and for that reason he should be given a salary. He has killed more Mau Mau than any member of the Security Forces." The question, however, is, if Kimathi has killed more African Kenyans why should the British border to kill him? The truth was that as Peter Baxter put it in his work "Ian Henderson and the hunt for Dedan kimathi" that "The operation to capture or kill Kimathi was undertaken on the understanding that only by his removal from the active theater could the matter of the Rebellion be finally laid to rest. Mau Mau no longer presented any particular threat to outside society, and in any case been superseded by the mainstream political process which was heading slowly but surely in the direction of majority rule, as it was throughout most of Africa, but so long as Kimathi remained at large the rebellion was active."

Baxter continued that "Dedan Kimathi was the high priest of Mau Mau. He was not the only gang leader operating in the forests of the central highlands, and nor was he consistently the most powerful, but he was the only one sufficiently imbued with the cultural and esoteric mystique necessary to project his image – like that of Che Guevara in the context of Cuba – as the defining iconography of the revolution."

Whilst the British used vile propaganda to discredit Dedan Kimathi as a bloodthirsty murderer, cultist and a terrorist, Kenyan nationalists and the people saw him as the heroic figurehead of the Mau Mau rebellion. He was later viewed with disdain by the Jomo Kenyatta regime and subsequent governments. In fact, the Kenya first president Kenyatta denounced Mau Mau and Kimathi, however, Kimathi and his fellow Mau Mau rebels are now officially recognised as heroes in the struggle for Kenyan independence by the incumbent government.

ortrait of Dedan Kimathi. Dedan Kimathi lies handcuffed on the ground shortly before his execution by the British colonial government. Kenya, 21 October 1956. Kenya, Eastern Africa, Africa

Nelson Mandela admitted that he was inspired by the freedom fighting strategies of Kenyan Mau Mau, especially their leader Dedan Kimathi. In is 1990s visit to Kenya, anti-apartheid activist Nelson Mandela publicly requested then President Daniel arap Moi to allow him visit the grave of Field Marshall Dedan Kimathi. Mandela had assumed that, being a key pillar in the fight against British colonialism in Kenya, Kimathi would obviously have a large, State-funded mausoleum extolling his valuable contributions in the fight and reflecting a national reverence for his sacrifices.

After asking for the whereabouts of Kimathi`s widow Eloise Mukami Kimathi as well as General China, one of the key leaders of the Mau Mau uprising, Mandela told thousands of Kenyans at Kasarani Stadium: “In my 27 years of imprisonment, I always saw the image of fighters such as Kimathi, China and others as candles in my long and hard war against injustice. It is an honour for any freedom fighter to pay respect to such heroes.”

The Standard of July 14, 1990 reported Mandela saying: “Kimathi died but the spirit of liberation remained alive and that’s why the people of Kenya are free today. How many sons and daughters have paid with their own lives because of demanding for their rights?”

Kimathi was born to wealthy family on 31 October 1920 in Thegenge Village Tetu division, Nyeri District. He was of the Ambui clan, one of the nine clans of the Agikuyu tribe in Kenya. Ambuis are hot-tempered and fearless that at one time they attacked the waters of River Gura with simis and spears after it had broken its banks and swept away their arrowroots. Kimathi`s father was polygamous and had 3 wives but he died before Kimathi was born. In recent well-researched biography on Dedan Kimathi, authored by the distinguished and veteran Kenyan journalist Joseph Karimi and published by Jomo Kenyatta Foundation (JFK), it is revealed that Kimathi`s father Wachuiri did not fathered him but "Ng’aragu, son of Wangima, an age mate of Wachiuri, fathered Kimathi. In the Agikuyu custom, age mates would “drop in at the house of an age mate and even sire a child without raising furore”. The author came by this information when he interviewed the hitherto, secretive and oath observing Mau Mau surviving leaders. Karimi writes "One of them, Yunis Nyamuhiu, Ng’aragu’s daughter, confirmed that indeed Kimathi is her half-brother."

Kimathi was raised by his mother, Waibuthi. He had 2 brothers, Wambararia and Wagura, and 2 sisters. He joined Karunaini Primary School aged 15, and went on to show intelligence. He was so good in would later use those language skills to write extensively before and during the Mau Mau uprising. He was a Debate Club member in his school and also showed special ability in poetry. As a result of his prowess in poetry and English that at one time a teacher gave him a goat as a gift.

Kimathi, having embraced education, shunned some traditions but when it came to circumcision, together with his close friend Wambugi Gichomoya, went to the Ihururu clinic instead of the river. In 1940, Kimathi enlisted in the British army. However, he was discharged after one month for drunkenness and persistent violence against his fellow recruits. He then drifted from job to job, including working as a swineherd and a primary school teacher, for which he was dismissed after accusations of violence against his pupils. Karimi also refutes the claim that Kimathi fought in the Second World War, as is widely believed, but "was recruited at King’s African Rifles to join World War II soldiers."

He later joined Tumutumu CMS School for his secondary learning in 1942. He became a prefect and went on to change things he did not like. Kimathi however balked at any discipline or control, and was constantly in trouble with his teachers. As a result he drifted in and out of education, and never fulfilled his potential of a bright academic career. Karimi writes "he left the school in protest against dictatorial ways of the principal, Rev William Scott Dickson."

In around 1948, whilst working in Ol Kalou, Kimathi came into close contact with members of the Kenya African Union. By 1950, he was secretary to the KAU branch at Ol Kalou, which was controlled by militant supporters of the Mau Mau cause. He would later be recruited into Mau Mau in 1951 by Paul Njeru, who had seen great leadership qualities in him. He was soon elected secretary of Thomson Fall’s Mau Mau Branch. Kimathi took into Mau Mau activities with fervour and became a fierce oath administrator.

The Kenyan freedom fighting activities started when young and unemployed men going by the name Riika ria bootie (the age group of 40), protested against forced labour and other inhumane treatment meted to the native Kenyans by the British settlers. Through the prominence of European missionaries, Christian groups emerged as the mouthpiece of the African public. The associations gave birth to conservative parties like Harry Thuku’s East African Association formed in 1921, which clamoured for better pay for African workers.

Thuku’s supporters in Murang’a would start an offshoot, Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) in 1924, headquartered in Kahuhia and with its main objective being reclaiming the land taken by Europeans. KCA sent Kenyatta to London in 1929 on the recommendation of James Beauttah. The first mission was unsuccessful and he was sent back again in May 1931. Before he left, writes Karimi, “it was a considered opinion that he took the KCA oath”. Mau Mau was a militant wing of KCA and began as the Land and Freedom Army, a militant Kikuyu army out to reclaim their land that they claimed had been gradually stripped from them by the British settlers. As the group's influence and membership widened it became a major threat to the colonialists. Some of them had returned from the World War II with revolutionary ideas exacerbated by the fact that after returning home, they were racially segregated by the same British whom they had faithfully fought for.

In November 1931, Kenyatta met Mahatma Gandhi, who shared his ideology of non-violence. Karimi says Gandhi inscribed in Kenyatta’s diary: “Truth and non-violence can deliver any nation from bondage.” This ideology would years later humiliate Kenyatta in the presence of the freedom fighters. “The freedom fighters, in a Kenya African Union (KAU) rally at Ruring’u showground, in which Kenyatta chaired on July 26, 1952 said armed struggle was “the only language the British understood”. In response, Kenyatta asked the gathered crowd of 50,000 if they would withstand the kicks of a donkey if he held its jaws. “The rally roared back affirmatively.” However, a month later, during a three-day KAU delegates conference, Kenyatta advocated for non-violence. He angered the freedom fighters, and he was forced out of the chairman’s seat. Kenyatta sat on the floor as directed for the next three hours.”

Kimathi as a fierce administrator or High priest who presided over oath taking in Mau Mau, believed strongly in compelling fellow Kikuyu by way of oath to bring solidarity to the independence movement. To achieve this, he administered beatings and carried a double-barrelled shotgun. His activities with the group made him a target of the colonial government, and he was briefly arrested that same year but escaped with the help of local police. This marked the beginning of his violent uprising. He formed the Kenya Defence Council to co-ordinate all forest fighters in 1953.

Soon after, Kenyatta and his colleagues in the famous Kapenguria six list were arrested during the State of Emergency. Behind bars, there was bad blood between Kenyatta and KCA. The colonial government at the same time was painstakingly plotting for a succession plan.

Karimi writes that in wondering who would take over, there was the choice of Dedan Kimathi, who after arrest was popular with the Mau Mau members, and Kenyatta. However, the prospects of a Kimathi leadership sent “shivers down the colonial government’s spine. They wanted to groom a man who would bring about political equilibrium the moment they relinquished power. The compromise candidate was Kenyatta”

In 1956, on 21 October exactly four years to the day since the start of the uprising, Kimathi was arrested in the Nyeri forest by a group led by Ian Henderson.

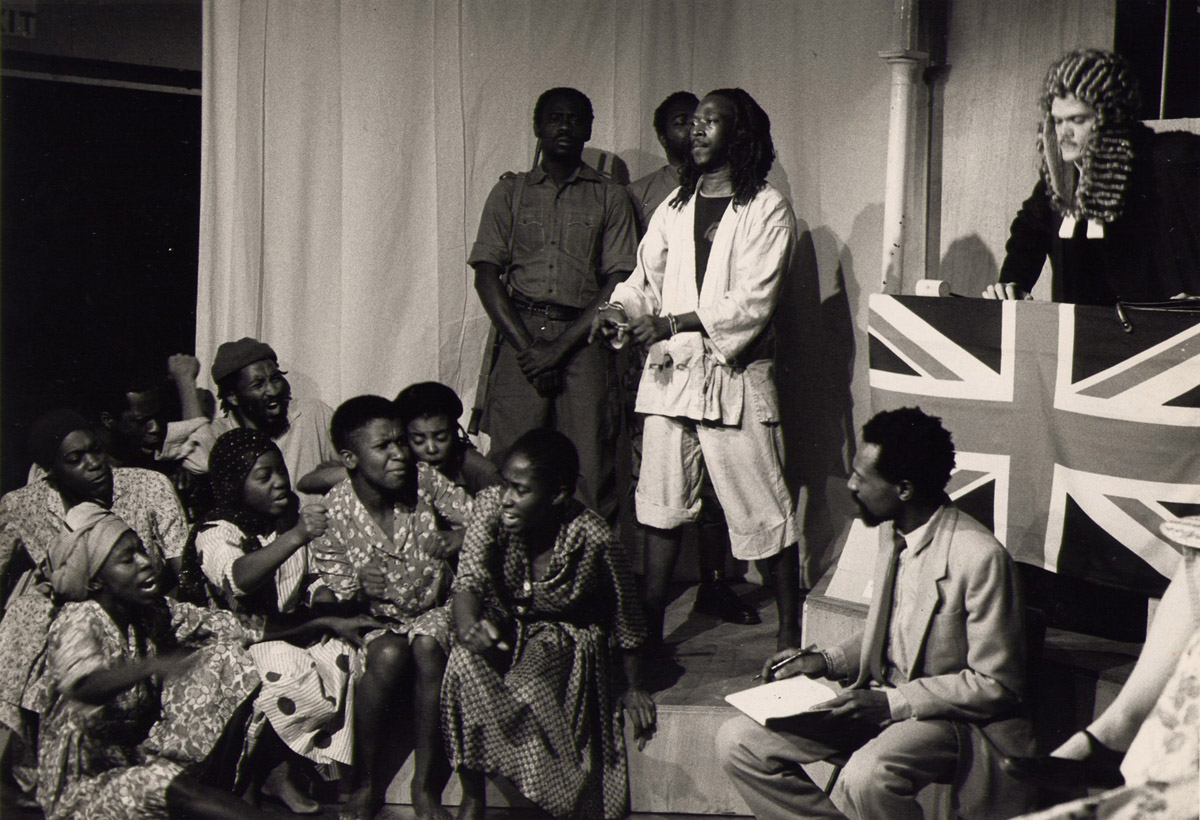

Play of Ngugi wa thiongo`s "trial of Dedan Kimathi"

The Hunt for Dedan Kithathi

The tale of the hunt for Kimathi, mounted by the Kenya Police, and spearheaded by Henderson, tells the story of one man’s utter determination to account for another against a backdrop of the generally bizarre and violent Mau Mau Rebellion. Ian Henderson grew up, as many other white boys in Africa did at that time, with a rifle in his hand, with unrestricted liberty of movement and the fealty of any number of black youth who would have been his childhood playmates. From them he gained fluency in both the famously difficult and abstruse Kikuyu language as well as Kikuyu lifestyles and culture. It is believed that he took traditional Kikuyu mystic powers. Beyond that he was gifted with a third eye, some would say a hunters sixth sense, that was comparable in some ways to Kimathi’s God-given mysticism.

Henderson achieved fame amongst his peers during the Emergency as a policeman, and then as a member of the local British internal intelligence organization, Special Branch. He was recognized, and rewarded, by the Crown for exemplary service during the Kenya Emergency, with outgoing Governor, Sir Evelyn Baring, conceding that Henderson did more to suppress the Mau Mau Rebellion than any other white person in the territory. Certainly Henderson killed, or accounted for the deaths of a large number of high profile blacks during the course of the crisis, and he was largely responsible for compiling the evidence in the famously skewed trial of Jomo Kenyatta, the honorary if not practical leader of African resistance in Kenya. As a consequence Henderson was no particular friend of the black man and was deported soon after Kenyan independence and never invited back.

He then went on to serve as intelligence supremo in Bahrain where he gained a reputation over three decades, not very different from that which he had departed from in Kenya, as a sadistic, torture prone functionary of a coercive and unrepresentative regime. The Butcher of Bahrain became his nomenclature upon his retirement, and many have been the calls for an inquiry into the conduct of this highly secretive, almost subterranean man."

By 1956 the offensive spirit of the Mau Mau had been lost. The imperial response had been so overwhelming and so accurately applied that the movement by then amounted to nothing more than a handful of remnant gangs roaming the vast forests of Mount Kenya and the Aberdares with no greater purpose than their own survival. The British – Ian Henderson in this case, among others – had by then began to deploy pseudo gangs to root out and run to ground these remnant units still remaining. The pseudos, contrary to popular mythology, very rarely included blacked-up white men, but were in fact almost entirely made up of captured and turned guerrillas who returned to the forest to track down and capture or kill their former comrades.

The operation to capture or kill Kimathi was undertaken on the understanding that only by his removal from the active theater could the matter of the Rebellion be finally laid to rest. Mau Mau no longer presented any particular threat to outside society, and in any case been superseded by the mainstream political process which was heading slowly but surely in the direction of majority rule, as it was throughout most of Africa, but so long as Kimathi remained at large the rebellion was active.Henderson, for his part, was quite obviously obsessed with bringing the famed guerrilla leader in, either dead or alive, quite as Kimathi was obsessed by his own survival. For this the guerrilla leader began to rely increasingly on his higher spiritual direction and the violent cleansing of his immediate corps of followers who needed only the most minor transgression of daily protocol to find themselves under suspicion of collaboration.

The process began with the capture of a pair of middle ranking fighters in the Aberdare forest in December 1955, in the broad vicinity of where Kimathi was known to be hiding. At that time it was estimated that there were fewer than 1500 active fighters remaining in the forest aligned to a handful of key leaders. Kimathi himself commanded a large following of extremely committed and ‘hard core’ fighters, with an inner circle of bodyguards whose loyalty was unimpeachable.

‘Turning’ these two captures was not difficult. The development of pseudo gangs had shown from the onset that it was surprisingly easy to realign captured guerrillas, arm them and then send them back into the forest to operate against their former comrades. Part of the reason for this was that by the time pseudo ops came into concentrated use the balance had shifted and the Mau Mau were manifestly on the run. Survival in the forests had become extremely difficult once access to the Kikuyu Reserve had been cut by an airtight cordon, at which point continued existence became dependent on theft from white commercial farms or directly off the land within the forest. Internecine fighting had also become common as guerrilla units began to suspect one another, and as a consequence tended to keep as far away from one another as possible. The sheer difficulty of life, and the threat upon capture of a swift trial and the gallows, meant that when a reprieve was offered in exchange for cooperation it was rarely declined.

African Kenyan police who helped in the arrest of Dedan Kimathi being congratulated

This small corps of able and knowledgeable men was added to over the course of 1956 as the loyal elements of the Mau Mau gradually diminished and more captures fell into the hands of Henderson and his force. Henderson himself played only a very limited active role, but it was he at the center of command who plotted the sequence of events the irrevocably tightened the noose around Kimathi’s neck. As more and more men were captured, and as Kimathi’s personal force diminished, his survival became dependent on his own reserves of personal cunning and incisive intelligence, along with what was universally recognized as extraordinary good luck – the luck that many around him attributed to his status of Ngai’s favored son.

In October 1956 the drama ended with an isolated and surrounded Kimathi forced by hunger to leave the embrace of the forest and venture into the open country of the Kikuyu Reserve. There his luck finally deserted him and he was wounded by a Home Guard patrol and later arrested by elements of Henderson’s force.

Kimathi`s capture marked the end of the forest war. He was sentenced to death by a court presided by Chief Justice O'Connor and an all-black jury of Kenyans, while he was in a hospital bed at the General Hospital Nyeri. In the early morning of 18 February 1957 he was executed by the colonial government. The hanging took place at the Kamiti Maximum Security Prison. He was buried in an unmarked grave, and his burial site remains unknown.

Kimathi was married to Mukami Kimathi. Among their children are sons Wachiuri and Maina and daughters Nyawira and Wanjugu.[8] In 2010, Kimathi's widow requested that the search for her husband's body be renewed so she could give him a proper burial

To some Kenyans and the aged Mau Mau freedom fighters "as long as Kimathi lies in Kamiti Prison, a colonial prison, we cannot be free." Daniel Branch writing about Kimathi`s unknown grave said "Modern Kenyan history is full of eloquent corpses. Certain remains, through the debates and silences that surround them, articulate lucidly what it has meant to be a citizen or subject of colonial and post-colonial Kenya. It is unsurprising then that Kenyans and their historians have, like other Africanist historians, found discussions of the cultural practices surrounding death and dying fruitful for scholarly enquiry.3Few corpses, though, have attracted such prolonged attention as that of Dedan Kimathi, one of the Mau Mau rebellion’s leaders executed by the British authorities in 1957."

However Karimi in his new thorough research work has giving fresh information especially coming from Mau Mau members who knew Kimathi, ”Most people hunger to see Kimathi’s grave, which is believed to be at Kamiti Prison, where he was hanged. Karimi gets new information from his interviewees and is convinced that the actual burial place of the Mau Mau hero is at an unmarked grave at Langata Cemetery."

Over the years, there have been mixed stories about where Kimathi was buried, including King’ong’o Prison in Nyeri.

Kimathi is viewed as a national hero by the Kenyan people, and the government has erected a bronze statue of "Freedom Fighter Dedan Kimathi" on a graphite plinth, in central Nairobi. On the anniversary of the day he was executed (11 December), in 2006, the statue of Kimathi was unveiled in Nairobi city centre. Kimathi, clad in military regalia, holds a rifle on the right hand and a dagger on the other, symbolising the last weapons he held in his struggle. This official celebration of Mau Mau is in marked contrast to a post-colonial norm of all previous Kenyan governments regard of the Mau Mau as terrorists. Such a turnabout has attracted praise from Kenyans as a long overdue recognition of the Mau Mau for their part in the struggle for independence. Elsewhere, The Dedan Kimathi Stadium in Nyeri was renamed after him, it was formerly known as Kamukunji Grounds. There is also Kimathi University College of Technology at Nyeri, Kenya which is named after him.

Dedan Kimathi`s statue

In popular culture, Dedan Kimathi was given a heroic immortality in Micere Mugo and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o`s best-selling play "The Trial of Dedan Kimathi." Dedan Kimathi placed a respectable 32 position in the 2004 edition of New African magazine (The most authoritative Pan-African Magazine), "100 Greatest Africans" list.

Dedan Kimathi`s Farewell Letter

The letter dated was written on 17th February 1957, one day before Kimathi was executed by the British Colonial Government in Kenya on 18th February 1957. The letter is addressed to one Father Marino of Catholic Mission, P.O. Box 25, Nyeri, Kenya.

The source of the letter is the Kenya National Archives, where a typed copy of the same was on display at the Kenya National Archives Public Gallery in the 1990s, since when it has been brought down. However members of the public can on request, get a typed photocopy of Kimathi’s said below letter at the Kenya National Archives. It remains unclear if the original handwritten copy of Kimathi’s said below letter still exists, and if it still does, in whose possession it is. Contents of Kimathi’s said letter of 17th February 1957 reproduced below verbatim…

--------------------------------

Dedan Kimathi

C/O H.M Prison (i.e. Her Majesty’s Prison)

17th February 1957

Father Marino

Catholic Mission

P.O. Box 25

Nyeri

Dear Father,

It is about one O’clock night that I have picked up my pencil and paper so that I may remember you and your beloved friends and friends before the time is over.

I am so busy and so happy preparing for heaven tomorrow the 18th February 1957. Only to let you know that Father Whellam came in to see me here in my prison room as soon as he received the information regarding my arrival. He is still a dear kind person as I did not firstly expect. He visits me very often and gives me sufficient encouragement possible. He provided me with important books with more that all have set a burning light throughout my way to paradise, such as :-

1. Students Catholic Doctrine

2. In the likeness of Christ

3. The New Testament

4. How to understand the Mass

5. The appearance of the Virgin at Grotto of Lourdes

6. Prayer book in Kikuyu

7. The Virgin Mary of Fatima

8. The cross of the Rosary etc.

I want to make it ever memorial to you and all that only Father Whellam that came to see me on Christmas day while I had many coming on the other weeks and days. Sorry that they did not remember me during the birth of our Lord and Savior. Pity also that they forgot me during such a merry day.

I have already discussed the matter with him and I am sure that he will inform you all.

Only a question of getting my son to school. He is far from many of your schools, but I trust that something must be done to see that he starts earlier under your care etc.

Do not fail from seeing my mother who is very old and to comfort her even though that she is so much sorrowful.

My wife is here. She is detained at Kamiti Prison and I suggest that she will be released some time. I would like her to be comforted by sisters e.g. Sister Modester, etc. for she too feels lonely. And if by any possibility she can be near the mission as near Mathari so that she may be so close to the sisters and to the church.

I conclude by telling you only to do me favor by getting education to my son.

Farewell to the world and all its belongings, I say and best wishes I say to my friends with whom we shall not meet in this busy world.

Please pass my complements and best wishes to all who read Wathiomo Mukinyu. Remember me too to the Fathers, Brothers and Sisters.

With good hope and best wishes,

I remain dear Father

Yours Loving, and Departing Convert

D. Kimathi

The Spoils of War: Why Do We Celebrate Kenyatta, not Kimathi, Day?

Monday, October 19, 2009 - 06:27, by Patrick GatharaIn the early hours of 21st October, 1952, Jomo Kenyatta was arrested peacefully at his Gatundu home, charged with managing the so-called Mau Mau uprising and on 8 April 1953 sentenced to 7 years hard labour. In an uncanny historical coincidence, 4 years to the day after Kenyatta’s arrest, on 21st October, 1956, the leader of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army and self-proclaimed President of Kenya, Dedan Kimathi, was shot and captured in the forests near Nyeri. Clad in a leopard skin and carrying a .38 revolver, Kimathi was charged with carrying a lethal weapon –a capital offence under the emergency regulations then governing Kenya. He was sentenced to death and hanged at Kamiti prison on 18th February 1957.

Born almost a quarter of a century apart, the two men were destined to change the future of the Kenya colony. They each received their early education at Church of Scotland missionary schools. To pay the school fees, Kenyatta worked as a houseboy and cook for a white settler while Kimathi collected seedlings for the forestry department. Both were religiously inclined. Kenyatta converted to Christianity in 1914 assuming the name John Peter, which he then changed to Johnstone Kamau. Kimathi was reported to carry a Bible regularly. However while the former completed his education and went on to secure opportunities which saw him rise to general secretary Kikuyu Central Association in 1928 and (after a 15 year sojourn in the UK) the eventual leadership of the Kenya African Union, the latter dropped out for a lack of fees, was kicked out of the Army for misconduct, joined the militant wing of the then defunct KCA in 1951 and was elected as a local branch secretary of KAU in Ol' Kalou and Thomson's Falls area in 1952.

An interesting encounter between the two men is related by Munene Macharia, Professor of History and International Relations at the United States International University. “One day at Kaloleni, Nairobi, (so say those who were there) Kenyatta turned to Jesse Kariuki, one of his top KCA comrades and asked in Gikuyu language: ‘Jesse, andu niaiganu?’ (Are there enough people?). Before Kariuki could respond, a brash young man named Dedan Kimathi shouted ‘Ii niaiganu,’ (Yes, they are enough). On hearing Kimathi, Kenyatta reportedly took out his handkerchief, wiped his eyes and asked ‘Nimukwenda wiyathi?’ (Do you want independence?). And the public responded ‘Ii nitukwenda’ (Yes, we want it). Kenyatta then remarked, ‘Muti uyu wa wiyathi nduitagiririo mai; uitagiririo thakame. Ningunyita Kiongo-i, nimukumiriria mateke?’ (the tree of freedom is not nurtured by water but by blood. I will hold the bull by the horn, will you withstand the kicks?) ‘Ii’ (Yes), the people responded.”

That same year marked the beginning of the uprising. At about the same time Kenyatta was prevailed upon by the colonial government to curse the “secret society called Mau Mau” saying they should “go to the roots of the mikongoe tree”, Kimathi was briefly detained for his oathing activities, escaped with the help of local police and fled to the forest. In 1953, as Kenyatta declared in open court “ndiui Mau Mau” (I do not know Mau Mau, I have no connection with it) and that violence would never bring harmony, Kimathi formed the Kenya Defence Council to co-ordinate all forest fighters. That same year, as related by Gatimu Maina in his paper, Paths of the Mau Mau Revolution: Victory and Glory Usurped, he launched the only known communication between his movement and the outside world, the KLFA Charter, which attempted to explain its political position and programme of the movement. The Charter was sent to the British government. Copies were circulated to the Indian, Egyptian, French, American, and Russian governments. Pan-Africanists such as Kwame Nkurumah of Ghana, George Padmore and W.E. B. Dubois were also sent copies. To whip public support in Britain, a copy was sent to Fenner Brockway, who was a sympathizer of the Mau Mau cause. The thrust of the Charter was self-government for Kenya with an African judiciary based on African laws, African control of the economy and the withdrawal of British armed forces from Kenya. The launching of the KLFA Charter, coupled with the sustained armed struggle and the eventual creation of the Kenya Parliament with Kimathi as its President in the forests on February 5, 1954 constituted, in Gatimu’s opinion, a unilateral declaration of independence for Kenya by the KLFA.

The British took the threat posed by the KLFA very seriously. On the same night Kenyatta was arrested, a State of Emergency had been declared and British military reinforcements began to arrive in the colony. A regiment of British soldiers was flown in from the Suez Canal Zone. The Kenya Regiment (composed of European settlers) was called up. Units of the King's African Rifles arrived from neighbouring Tanganyika and Uganda. In total, according to Basil Davidson, Britain and the Kenya colonial authorities mobilized 50,000 troops for the war armed with bomber airplanes, tanks, personnel carriers and other sophisticated weapons. These were ranged against Kimathi’s estimated 10,000-25,000 guerillas armed with rifles, shotguns, homemade guns, and grenades and crude traditional weapons of all kinds.

In the forest Kimathi had to contend with emerging splits, especially between the illiterate and the educated. He had himself usurped the overall leadership of the movement from the unlettered General Stanley Mathenge who, unlike Kimathi, had military experience. As their rivalry became generalized, the educated fighters favoured Kimathi’s Parliament while the rest preferred Mathenge’s Kenya Riigi. Matters came to a head in 1955 when, according to former fighter Field Marshal Muthoni-Kirima, the colonial government “suggested a truce, that the insurgents and the colonialists start exchanging letters before they could meet physically and negotiate a ceasefire.” Kimathi took a dim view of this proposal, fearing it to be a trick, and forbade any contact with the British. However, Mathenge went ahead to meet with them, incurring the wrath of Kimathi and narrowly escaping the death sentence at his trial before the Parliament. This however did not appear to dissuade him as a week later he was reported to have had more meetings with the British. An enraged Kimathi ordered that Mathenge be brought to him alive, but the latter went into hiding and was reported to have fled to Ethiopia. (This was a precursor of what was to happen to the KLFA fighters when they emerged from the forest and stepped into an independent Kenya governed by the better educated sons of collaborators.)

By 1955, though, the brutal British tactics were beginning to tell. The forests of Mount Kenya, where the KLFA had their base camps, were designated a "prohibited area" and were heavily bombed. People living on the fringes of the forest were evicted from the land, their animals confiscated and crops and huts burned to clear the way for the "free fire zone" where any black man could be shot on sight. In fact, rewards were offered to army and police units that produced the largest number of 'Mau Mau' corpses, the hands of which were chopped off to make fingerprinting easier. The entire 1.5 million rural Kikuyu population were forcibly resettled into barbed-wire fenced villages, overseen by watch-towers. Continuing urban insurgency was smashed by the aptly named Operation Anvil in April 1954, which effectively arrested all Kikuyu in Nairobi. The back of the insurgency was broken and one by one the forest commanders fell. Eventually, after a 10 month man-hunt, Kimathi himself was captured, tried and hanged.

Meanwhile, Kenyatta, convicted after a five-month trial on the perjured testimony of Rawson Macharia, was sentenced on April 8, 1953 to seven year’s imprisonment with hard labor and indefinite restriction thereafter. His subsequent appeal was refused by the British Privy Council in 1954. On April 14, 1959, Kenyatta completed his sentence at Lokitaung but remained in restriction at Lodwar. Later, he was moved to Maralal, where he remained until August 1961. On August 14, 1961, he was allowed to return to his Gatundu home. On August 21, 1961, nine years after his arrest, he was freed from all restrictions.

Though he was not directly connected to the insurgency, his political rise after imprisonment was undoubtedly a direct result of the Mau-Mau activities. In 1961 Kenya was on track towards self-government and he was hailed as the country’s independence leader. He assumed the leadership of the Kenya African National Union (KANU), a political party formed while he was in prison and in 1963 led it to an electoral victory. He became prime minister of an independent Kenya on 12th December 1963 and a year later, when Kenya became a republic, Kenyatta was declared its first president, more than 10 years after Kimathi had claimed the title for himself.

Over the course of half a century, Kenya’s independence war has entered into the realm of legend, with little to distinguish between fact and fiction. Many who then opposed or shunned the insurgency nowadays proclaim themselves to be at its forefront, while the real fighters languish in long-forgotten and overgrown graves or are still awaiting the recognition and rewards they insist are due them. Just as Kimathi usurped the uneducated Mathenge’s authority in the forest, so the collaborators and their offspring inherited his uprising.

The name attached to the movement itself betrays this. While initially it had no name (the Kikuyu had called it Muingi ("The Movement"), Muigwithania ("The Understanding"), Muma wa Uiguano ("The Oath of Unity") or simply "The KCA", after the Kikuyu Central Association that created the impetus for the insurgency), according to Bildad Kaggia, the movement had been using the Kiswahili word muhimu (important) as a password for the movement and its activities. After muhimu declared an open war on the British colonial government, the combat forces referred to themselves as the Kenya Land and Freedom Army. The British though called it Mau Mau, a bastardised name given to them by the settlers. In the 1953 Charter, Kimathi introduced his movement stating: “We reject being called [Mau Mau or] terrorists for demanding our people’s rights. [It is derogatory]. We are the Kenya Land [and] Freedom Army.” Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki, who was interned in prison camps from 1953 to 1960, and later murdered by Kenyatta's agents, talked of the KLFA saying: "The world knows it by a title of abuse and ridicule with which it was described by one of its bitterest opponents." To this day, however, the appendage Mau Mau remains.

Neither has the derogatory nature of the term changed. The Merriam-Webster Online dictionary defines the verb to “mau-mau” as “to intimidate (as an official) by hostile confrontation or threats”. In 2002, right-wing US columnist Ann Coulter, outraged that Halle Berry won an Oscar, complained that the Black artist had "successfully mau-maued her way to a Best Actress Award." In 1993, Former US Vice President Daniel Quayle's chief of staff, William Kristol, said Carol Mosely Braun "mau-maued" the U.S. Senate when, as the only African American woman member in the Senate's history, she stopped a charter renewal for the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

The statistics of the KLFA uprising are also a source of perennial controversy. According to the British government, some 32 white civilians, 63 white military and 527 'loyalists' were killed. In contrast, 11,503 Africans died. Other sources have the Kikuyu death toll at anywhere from 20,000-30,000 with 10,527 fighters killed in action. One thing is not in dispute though. The British losses were remarkably light, with less than 100 dead. What accounts for this discrepancy? Was the conflict, as some (including the British) have termed it, less about aspirations to nationhood and more of a civil war within the Kikuyu community?

In a paper entitled Emergency in Kenya: Kikuyu and the Mau Mau Insurrection, Major Roger D. Hughes of the US Marine Corps says about the conflict: “The Mau Mau movement is usually viewed strictly as being politically motivated toward national independence. The less popular view is endorsed herein, that two separate, multi-faceted movements existed, one motivated by nationalism, and the other by a blind, irrational quest for revenge. In the process of each attempting to exploit the other for self-serving purposes, they became uncontrollably intertwined, which resulted in near disaster for the Kikuyu tribe. Totally lacking in quality intelligence regarding the origins of Mau Mau at the outbreak of hostilities in 1952, colonial forces struck out blindly to suppress the violence and treated the movements as one. Thus, the Military resolution is traced through 1956, when the preponderance of hostilities were finally suppressed in what seemed at that time more like an intra-tribal civil war than a war of independence.”

As related by Marshall S. Clough in his book Mau Mau memoirs: History, Pemory, and Politics, “the Gikuyu were the angriest and the most internally divided of the major ethnic groups in Kenya. Colonial rule had affected them deeply, and for two generations they had suffered from its impositions and responded to the opportunities it had offered more than any other Africans. The British authorities and their policies tended to push the Gikuyu together, but for most the closer ties to lineage, locality and district remained more important than loyalty to the ethnic group as a whole. Ever since the founding of the Kikuyu Association (KA) in 1919, their politicians had protested such grievances as land alienation in Kiambu and Nyeri, the treatment of squatters in the Rift Valley, the carrying of passes, and the non-representation of Africans in the Legislative Council. In protest politics, however, disunity had been as typical a common front, as witnessed by the division between the KA and the East African Association (EAA) in 1921 and between the KA and the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA) in the late 1920s. Religious disputes, emerging originally from the cliterodectomy conflict of 1929-1931, divided them further among animists, followers of mission Christianity, Christian independents, and followers of prophetic sects (the arathi). Divisions between educated and uneducated, landed and landless, rich and poor had widened in the interwar period. Moreover, Gikuyu members of the colonial authority structure, especially chiefs, had often clashed with politicians and these conflicts would grow more intense in the postwar period as the second colonial generation entered politics.”

And what of tactics? Both sides utilised the tactics of terror and neither spared innocents. Just compare these two reports, one by Peter Swan, a British policeman who guarded Kimathi after his capture:

The Mau Mau 'Freedom Fighters' were no more than thugs whose terrorist activities were directed mainly at their own tribesman than at the 'whites'. Having come across Meru women, gutted with an unborn child torn from them; children whose heads had been cracked open; an old couple that where burnt alive after being ham-strung to make sure that they couldn't get away, it was difficult for me and the twenty African policeman to have any sympathy for those Mau Mau that we encountered. We took no prisoners. To hear them classed as heroes' of the day goes against the grain.

Another account from an Australian living in Kenya during the ‘Emergency’:

We was joined by two of [a settler named] Bill’s mates in another Land Rover and just about dawn we seen two Africans crossing the road ahead. Bill fired a shot across their bow and they put their hands up. I tried to tell Bill that those lads, hardly more than boys they was, didn’t look like Mickeys (Mau Mau) to me but he says, “They’re Kukes and that’s enough for me”. Well he roughs them up some but they say they don’t know where the gang of Mickeys went to, so he gets some rope and ties one to the rear bumper of his Land Rover by his ankles. He drives off a little ways, not too fast you know, and the poor black bastard is trying to keep from ploughing the road with his nose. The other cobbers are laughing and saying, “put it in high gear Bill” and such as that, but Bill gets out and says, “Last chance, Nugu (baboon), where’s that gang?” The African boy keeps saying he’s not Mau Mau, but Bill takes off like a bat out of hell. When he comes back, the nigger wasn’t much more than pulp. He didn’t have any face left at all. So Bill and his mates tie the other one to the bumper and ask him the same question. He’s begging them to let him go but old Bill takes off again and after a while he comes back with another dead Mickey. They just left the two of them there in the road.

Even tales of Kimathi himself tend to differ with a 1956 TIME Magazine article titled "The Terrorist" saying of him:

There was no fiercer character in all the jungle than Dedan Kimathi, a scarred, stocky ex-clerk who had fought and jockeyed his way to the leadership of all the guerrillas. Not content with his popular title, "General Russia," Dedan capped his arrogance by calling himself Field Marshal Sir Dedan Kimathi and appointing a parliament of his own to preside over...A refugee captured by Kenya police as he left Kimathi's camp recently has provided a vivid picture of the once great chieftain in his twilight hour. Broken in health and mind, 35-year-old Dedan Kimathi now spends his days making wild speeches to the jungle trees and his nights raving endlessly. He lies on a litter of branches, blubbering and blabbering about reform in the Liberation army, while his friends search the woods for monkeys to eat. Whenever a police patrol comes near, the 20 loyal henchmen (and teen-age henchwomen) who still surround him hustle Kimathi into a nearby cave and gag him to keep him quiet.

Peter Swan, quoted above, paints an entirely different picture of the man:

Our first hours together were almost silent. My command of Kikuyu language was reduced to the long drawn out greetings 'Moogerrrh' which should have elicited the reply 'Moogerrhni'. His command of Kiswahili and mine were similar, in that we were both well versed in what was loosely termed Kaffir Swahili. He was, I discovered, soon after joining him in the hospital, well versed in English and we later spent time swapping tales of our bush activities in that language. His wound was in the thigh and he had to be stretchered everywhere. Up to then he had received rudimentary first aid and he was still dressed in the leopard skins that had been his trade mark during his Mau Mau operations...Dedan Kimathi and I sat and read the books that I brought in to pass the time. Our conversations were occasional and without animosity or conflict on either side. He knew the penalty for his activity was death, and he expected that sentence. He believed that the sentence would not be executed and that he would survive. There was a quiet and distant confidence in his belief.

While the Mau Mau lost the military fight against the British, they lived to see the White Man ejected from Kenya. However, 50 years on, their land and legacy is now being stolen anew by those who collaborated with the colonialists. It seems to me that we, as Kenyans, have striven to erase from our minds what should be a heroic chapter in our common history. Instead we seem determined to construct a new tale in which the villains of yesterday become the heroes of today while the real fighters, their accomplishments, and eventual betrayal is consigned to history's dustbin.

On the 50th anniversary of his hanging, the Kenyan government took the step of honouring Kimathi by erecting a statue. A better memorial would be an honest retelling of the story of his struggle, and an explanation of why he was allowed to rot in an unmarked grave while Kenyatta’s body deserved the splendor of a mausoleum.

source:http://www.afrika.no/Detailed/18846.html

0 comments:

Post a Comment