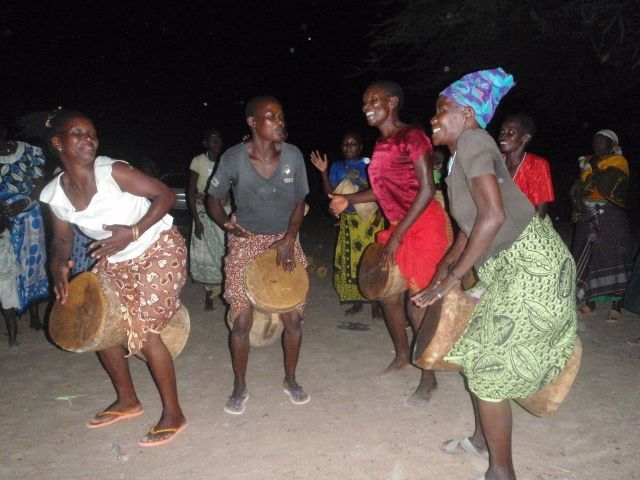

Maduma Wagogo group from Tanzania performing traditional African drumming. By /mapanakedmon

The Wagogo ocucupy a land in Tanzania known as Ugogo (Gogoland), and it covers most of Dodoma District. This region covers an area of 25,612 square miles, with an altitude of 480ms to 12ms above sea level (Cidosa, 1995).

Dr Hukwe Zawose, the legendary Wagogo traditional musician; Hukwe Ubi Zawose (b. Dodoma, Tanganyika, 1938 or 1940; d. Bagamoyo, Tanzania, December 30, 2003) was a prominent Tanzanian musician. He was a member of the Gogo ethnic group and played the ilimba, a large lamellophone similar to the mbira, as well as several other traditional instruments. He was also a highly regarded singer.

He came to national and international attention after Julius Nyerere invited him to live and work in Dar es Salaam. He also gained much attention for his work with Peter Gabriel, and released two albums (Chibite and Assembly) on Gabriel's Real World Records label. His final release before his death, Assembly, was a collaborative effort with producer/guitarist Michael Brook. At the 2005 Tanzania Music Awards he was given the Hall of fame award. His family is included in the 2009 documentary Throw Down Your Heart, which follows American banjo player Béla Fleck as he journeys through Africa.

It lies on an upland plateau of 3,000 feet and more, and comprises less than two percent of Tanzania's area and they comprise 3% (1,735,000 people) of the population of Tanzania.

Wagogo people performing traditional dance. By /mapanakedmon

Dodoma: Where the Elephant Sank

Dodoma (Tanzania, United Republic of) became a name before it became a town. There are different stories about how it happened. One story is that some Wagogo stole a herd of cattle from their southern neighbours the Wahehe; the Wagogo killed and ate the animals, preserving only the tails, and when the Wahehe came looking for the lost herd all they found were the tails sticking out of a patch of swampy ground. ''Look'', said the Wagogo, ''Your cattle have sunk in the mud, Idodomya''. Dodoma in chigogo means ''it has sunk''. There is yet another story which is most commonly accepted on the name Dodoma. An elephant came to drink at the nearby Kikuyu stream (so named after the Mikuyu fig trees growing on its banks) and got stuck in the mud. Some local people who saw it exclaimed ''Idodomya'' and from that time on the place became known as Idodomya, the place where it sank.

Wago

The musical Wagogo people of Dodoma, Tanzania. By /mapanakedmon

Language

Wagogo people speak Cigogo language which belongs to the eastern group of Bantu languages. Wagogo keep their Cigogo language strong within the family, even as they are now speaking Kiswahili, the official national language of Tanzania which is utilized in telecommunications, trade and commerce.

Wagogo people

History

Wagogo are indigenous Bantu people of Dodoma with half of their ruling group coming from Uhehe branch of Unyamwesi. They have always been where they are and have seen many tribes and adventurers passing through their Ugogo (land of Wagogo).

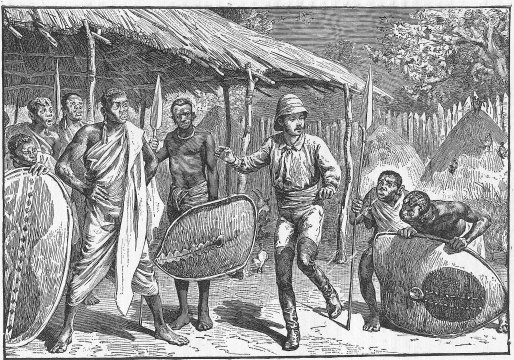

Wagogo warriors on their way to attend a trial for witchcraft, 1909-1910

Their name was invented sometime in the 19th century by the Nyamwezi ethnic group caravans passing through the area while it was still frontier territory. Richard Francis Burton claimed a very small population for it, saying only that a person could walk for two weeks and find only scattered Tembes.

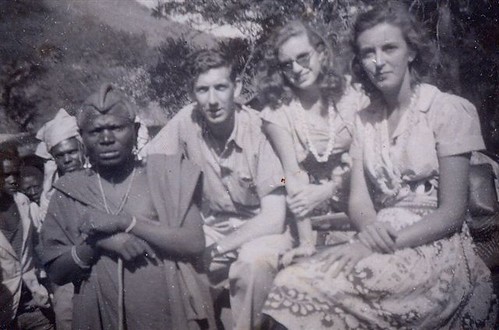

Young warrior from the Wagogo tribe at a cicumcision ceremony. 1947. By George-Rodger

There was and remains the problem of inadequate rain for crops and humans, the rainy season being short and erratic with frequent drought. In the 18th century the Wagogo were mostly pioneer colonists from Unyamwesi and Uhehe, and are often confused with the Sandawe and the Kaguru. Half the ruling group came from Uhehe. They had a long tradition of hunting and gathering, allowing the Wanyamwezi to carry the ivory to the coast, but had become agriculturalists with cattle by 1890. They continued, however, to have a low regard for working the land and are said to have treated their agricultural slaves badly.

The Wagogo experienced famine in 1881, 1885, and 1888–89 (just before Stokes' caravan arrived) and then again in 1894–95, and 1913–14. The main reason for the exceptional series of famines in Ugogo was its unreliable rainfall and the ensuing series of droughts.

In his book In Darkest Africa Henry M. Stanley, while "rescuing" Emin Pasha in order to bring him to the coast, writes,

"On the 26th we entered Muhalala, and on the 8th of November we had passed through Ugogo. There is no country in Africa that has excited greater interest in me than this. It is a ferment of trouble and distraction, and a rat's nest of petty annoyances that beset travelers from day to day while in it. No natives know so well how to aggrieve and be unpleasant to travelers. One would think there was a school somewhere in Ugogo to teach low cunning and vicious malice to the chiefs, who are masters in foxy-craft. Nineteen years ago I looked at this land and people with desiring eyes.

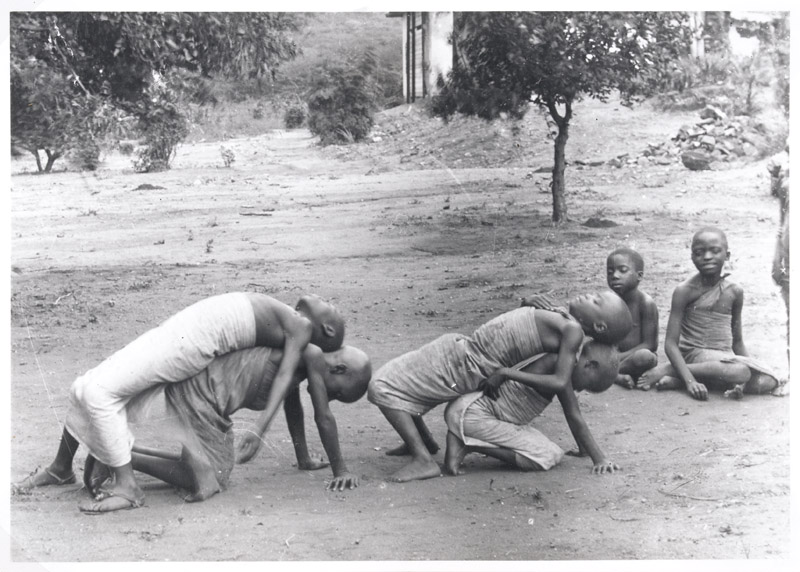

Wagogo boys playing 'chameleon', c.1919

I saw in it a field worth some effort to reclaim. In six months I felt sure Ugogo could be made lovely and orderly, a blessing to the inhabitants and to strangers, without any great expense or trouble. It would become a pleasant highway of human intercourse with far-away peoples, productive of wealth to the natives, and a comfort to caravans. I learned on arrival in Ugogo that I was forever debarred from the hope. It is to be the destiny of the Germans to carry out this work, and I envy them. It is the worst news of all that I shall never be able to drain this cesspool of iniquitous passion, extinguish the insolence of Wagogo chiefs, and make the land clean, healthy, and even beautiful of view. While my best wishes will accompany German efforts, my mind is clouded with a doubt that it will ever will be that fair land of rest and welcome I had dreamed of making it."

Wagogo boys playing 'giraffe', c.1919

The Wagogo are considered to be "sedentary but mobile cultivators" who subsist on cereals, but whose value system is paradoxically almost entirely orientated towards pastoralism, especially cattle-keeping. There are two seasons, cifuku (the rainy season) and cibahu (the dry season).

Their current mixed economy, is now of agriculture and herding, but most heavily depended on grain from agriculture. Traditionally, cultivation work parties of about twenty men and women were held from January through March, and lasted all day with a beer party at the end. People came from an area less than five miles; mostly they were close neighbors. Generally, however, agricultural cultivation played a secondary role to the livestock cycle.

Since grain can be extensively damaged by birds, bush pigs, wart hogs, and baboons, men and boys have the responsibility of protecting the fields, even at night. Several medicinal and supernatural methods were also used for protecting fields against wildlife and the evil influence of men.

In traditional agricultural practices, the average Wagogo did not possess a very large herd of cattle. Patterns changed, but it must be remembered that these cattle also belonged to relatives, kin, and clan members.

Wagogo people at Chamwino,Tanzania

Diet

The traditional staple food was a thick porridge (ugali) made from sorghum or millet flour. It was consumed with a side dish made from green vegetables, meat, or mhopota (churned milk). Milk, which was relatively scarce, especially during the long dry season, was consumed in several different ways. Only on certain occasions was meat consumed; cattle were never deliberately slaughtered for consumption. However, livestock had to be slaughtered during rituals or when the cattle were old, and could be used for such ceremonial feasts as childbirth, weddings, and funerals. Most neighbors shared in this consumption.

Wagogo women drummers. courtesy Martin Neil

Traditional society

Influenced by the Nyamwezi, Maasai, and Hehe, the Wagogo have historically been described as rude, brawling, and boundlessly inquisitive herders, with manners and fierce looks from a rough, raw way of life, physically intermixed with slaves from the west.

They had a truly miserable reputation among Europeans traveling through Ugogo, being considered suspicious, deceitful liars, insolent and cowardly. Emin Pasha, writing to his sister, reported, "We are now on the boundary of Ugogo, a country notorious for its winds, dust, scarcity of water and the impudence of its inhabitants". (He makes no mention of using the death of an Askari as an excuse to destroy nineteen villages and looting some 2,000 cattle.)

Boys of Wagogo tribe wear special headgear for Circumcision Ceremony, Tanganyika, Tanzania, 1948* George-Rodger

Social structure

Wagogo clans moved around a good deal, dropping ties to older groupings, adopting new links and family, new clan names, things to avoid, affiliations, and new ritual functions. The Gogo, in short, became different from what they were before.

While early European writers emphasized the political chiefs of the Wagogo, calling them 'Sultans' as was customary on the coast, and stressed their collection of the very profitable taxes (hongo), on scarce food and water, it was really the ritual leaders who influenced the entire country. They controlled rainmaking and fertility, medicines to protect against natural disasters or hazards, and prevented certain resources from being overly used. They were not to leave their "country," they were to be rich in cattle, decided on circumcision and initiation ceremonies, give supernatural protection for all undertakings and be arbitrators in homicide, witchcraft accusations, and serious assault.

The Wagogo placed considerable value on neighborliness. After having his physical needs met, a strange traveler would be accompanied many miles by the young men of a homestead in order to place him safely on his way. The homestead group was so fundamental to Gogo society that people who had died peculiarly, (struck down by lighting or a contagious disease) were thrown into the bush or the trunk of a baobab tree, for such a person had no homestead and could become an "evil spirit" who associated with sorcerers or witches.

Wagogo Mirungu

Family structure

Most brothers went to great lengths to assist their sisters, who often lived with their brothers in sickness until they recovered, for brothers have strong moral and legal obligations to fulfill these duties in cooperation with their sisters' husbands. Even later in life, sisters and brothers continue to visit each other, a wife never being fully incorporated into her husband's group.

Wagogo African queens of drums. By /mapanakedmon

Marriage

While the majority of Wagogo have only one wife at any given time, most found polygyny to be highly valued and carrying a high priority. It was the prerogative of older, well-established men. A reasonably prosperous man could hope to have two and sometimes three wives, and sometimes together.

Most marriages took place within a day's walking distance after agreement is reached on the number of livestock to be included in the bridewealth, only then is the transfer made. Even a hundred years later, bridewealth is still normally given entirely in livestock and a high proportion of court cases involve the giving or return of bridewealth. The divorce rate in Ugogo was very low, for few marriages ended in divorce. Even after divorce, all children born during the marriage belonged to the ex-husband, "where the cattle came from." "If you go somewhere and marry the child of others, then all your wife's relatives become your relatives, because you have married the child, and so you will love even them.("From Rigby's book Cattle and Kinship") Lovers of married women could never, however, claim their offspring. If a husband had given bridewealth for his wife who was pregnant before he married her, he must still accept paternity of the child.

Defense

Defense against the Kisongo, Maasai, and Wahehe was organized and based on age groups of warriors, much as the Maasai. This "military" organization was mostly used for local defense, although it could be used for cattle raids against others. When an alarm was sounded all able-bodied men were to take up arms and run towards the call (this did not always work smoothly).

source:http://mapanakedmon2010.wordpress.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gogo_people

Wagogo the musical people of Tanzania. By /mapanakedmon

Muheme musical Traditions and Makumbigawadala (rite of passage) ceremony

Transitions in the Social Functions of the Muheme Music Tradition of the Wagogo People of Dodoma, Tanzania

Kedmon Mapana

Department of Fine and Performing Arts University of Dar-es-Salaam Tanzania

The musical tradition of muheme is associated with various songs and dances performed during the Wagogo girls‟ initiation ceremony, makumbigawadala. The muheme music tradition has its own historyand socio-cultural context among the Wagogo people, as Vallejo (2007) notes. There is not a moment in the Wagogo`s life that does not have musical support and muheme, in its original context, is an example.

Makumbigawadala is an initiation ritual (rite of passage). It includes the circumcision, cigotogoto, within the ritual. This initiation ritual marks the transition of the female from being a girl to becoming a woman. The girls are taken to Makumbi which is the house where, after their circumcision has taken place, the girls stay for the rest of their initiation. The girl‟s initiation ritual is also called cigotogotocawadala or circumcision of girls.

Wagogo dancing group. courtesy Martin Neil

*Social function of muhemein the context of initiation/circumcision

Muheme as a music tradition appeared and was originally performed as part of the Wagogo girl` initiation/circumcision (Mapana 2007,Nyoni 1998) to serve the following gender-related and generic social functions:

To hide or ‘mask’ the sounds of the agony of the girls

Normally, when girls were circumcised they felt great pain. The pain caused the girls to scream loudly and in order to keep the screaming from being heard by outsiders, especially younger girls who, it was anticipated, would go through the same pain in the future, loud muheme was performed.ElisabatiMasholi, who used to be a circumciser, noted that: Calakwanzagotolawana, ng’omazatowagwakwamlilomuwahambeka. Sautizang’omazatazagakukumbilizasautizawana, sokowawonagausungumuwahahonowakugotolwa.

During the circumcision, the drums were played at a very high volume, so as to mask the sounds of the circumcised girls. The circumcision was very painful for them (E. Masholi, personal communication, October 13, 2006).

Wagogo male initiation dancers

This is supported by the function of the igunda musical instrument observed among the Wakaguru people from the Morogoro region of Tanzania which was played during boys‟ circumcision. Mlama (1973) found that “the one musical instrument which appears, [the] igunda, has limited significance in the play as such. The main purpose of its being blown is to make the boys‟ cries of pain inaudible to the people at the village. This is important because this society expects men to be able to endure hardship…Making cries inaudible, therefore, helps to maintain [the boys‟] manliness (p.60).

To educate the young girls

The song texts, learned by the girls in singing sessions after the circumcision and during the training sessions in the makumbi [initiation], provided the main teaching materials for training girls to learn behavior acceptable in the society. For example, these song lyrics contain instructions on how the girls should act when talking with their parents:

Ane kongo gwe-kongo nomliga kaya I swear that I cannot disrespect my elders

Hamba sogo-Mwiko nomliga kaya I cannot disrespect my father

Hamba nyina- Mwiko nomliga kaya. I cannot disrespect my mother.

The initiated girl is singing that she should behave herself as a grown woman. She should always be respectful of her elders. This kind of cultural education through muheme songs was described by different Gogo interviewees, including this one:

Cagotolagawana, nakwimbazinyimbo ho ciwapelemahweso,

wawenaheshimakwawalezinawanhuwose

We used to circumcise girls and dance for them in order to give them the discipline to respect their elders and other people, as well (M. Ngoli, personal communication, October 18, 2006).

To celebrate the communities acceptance of the girls change of status

Traditionally, a Gogo girl could not be considered an adult female until she had undergone this procedure. Consequently, a female could not marry without being circumcised. Communities celebrated the change in the circumcised girls‟ status from children to women:

Catowagang`omayamuheme, soko ye nyemo. Ai

yalisherehevyonowanawavinwanawawahapa, wanzawanhumtutu

Muheme was played because it was a sign of happiness after circumcision [whenthe] girls danced because they [were] happy to be [recognized as] grown up, now (J.Yohana, personal communication, October 16, 2006).

Wagogo dancing group. courtesy Martin Neil

To console the circumcised girls

Because the act of circumcision was painful, different songs were sung to comfort the circumcised or initiated girls. The following song lyrics provide an example:

Mpelawalimubigwe, mpelawalimubigwe, sesecausesanembazo

Mpelawalimubigwempelawalimubigwe, sesecausesanembazo

Look how beautiful you are; before circumcision you were not that beautiful.

This kind of song attempted to make the initiated girls feel that the circumcision process helped them to have a healthier body stronger physiologically. These songs texts were intended to save the girls accept the process as expected by the society:

Ng’omayamuhemeyawatazagawanawonowagotolwewehuliceviswanuhononyimbozikwimb

wa, zanozagawehulicevyonoainkhaniyasinjenzi, langakilamunhuyopkolelamumo.

The dance was used to console the circumcised girls so that they could see the action as a normal thing which everybody had to go through. Masholi continues by saying that:

Ng’omaaiwatowelwagawanyamuluzi, ikuwakumbucizavyonocivinilwa, nawacisangalaza.

It was used by the circumcised girls to build a feeling of pride and of being superior because they had gone through the process of circumcision (E. Masholi, personal communication, October 13, 2006).

The Zawose family performing a traditional dance with the schools of Abu Dhabi. http://canvas-of-light.blogspot.com/

This is similar to the Wagogo boys` circumcision in which the cipandemusic tradition is played for the same purpose. Vallejo, (2007) suggests that “ it is also used as a way to relieve the pain of the future initiated in the precise moment when the cut in the skin is being done. In order to achieve this purpose, the men surround the boy that is going to be circumcised and, at the warning signal of the honondulele (antelope horn), they project their voices towards him while they sing the polyphonic section of the cipande

To entertain

The music was used to entertain people in the community. During the initiation period, people, particularly women, used to come together to celebrate the event. Songs were sung and the dance appeared for the purpose of entertainment. In one song, for example the text says:

Chazahoihe, ahechazakumlamusenyi. Mnyakayanhoweleluchenzetezajehiyihiyo,

ahechazakumlamusenyi

We have come to celebrate the circumcision. Children and parents, do not feel lonely,

we have come to celebrate

Wagogo musicians

These song lyrics indicate that the initiated girls and their parents were not celebrating alone, but they had other people accompanying them. During the celebration, women used to drink local beer and sometimes cows were killed. The celebration was a very big event:

Yaliinanhuninzyombahasana. Ng`omayasangalazagawanhu, hanjiwaulagagang`ombe,

wakutelekaujimbi, nawakung`wa, aluhonowagala, howakutowang`omamunomuno, so

nyemoyacigotogoto.

The dance was performed because it had great importance; the importance was reflected in their happiness. People were happy and used to drink local beer to celebrate the initiation event (E.Malebeto, personal communication, October 18, 2006).

To mobilize the community and emphasize the strength of the Wagogo culture

The circumcision and its` music tradition was performed every year. It brought many people to a particular place. By making it an annual event,in a specific place in Ugogo, the practice was planted as a tradition in the society. It was inherited and there was social continuity in its performance:

Cigotogotocanzakatalicilawahenga. Cavinagawanakuwapelaielimu, watujemahwesomaswanu.

Cembaga ne zinyimbokuwaletawahnu ho watugemafundishoganamnayakuheshiana.

Since the time of our grandfathers, female circumcision brought people together. This was a school to educate the girls and the society as whole to be respectful and pleased with Wagogo customs (G. Maile, personal communication, October 17, 2006).

Wagogo guiter. courtesy Martin Neil

The transition of muheme begins

It is believed that the natural life of muheme began as music for girls‟ initiation, or makumbigawadala(Nyoni, 1998). Muheme music and girls‟ circumcision culture were inseparable. The literature provides evidence that the Wagogo culture of circumcising girls was already strong in the 1800s in which neighbors started imitating the culture. This indicates that ,muheme music was strong too.

The Zawose family, spreading the music of the Wagogo people of Tanzania.http://canvas-of-light.blogspot.com/

Peterson, (2006) found that “in 1889, the missionary Wood spent several days in the Kaguru village of Chief Sekwao. He was disconcerted to find that some of the girls there had recently been circumcised, because Kaguru did not normally cut their girls. “I asked Sekwao why he allowed them to follow the Gogo custom in this respect”, wrote Wood. He said it was because the women and young girls were so anxious for it (p.995).

This was followed over time by a period of transition during which it became music widely used for political gatherings, celebrations and other secular entertainment events in the 1960s, after Tanganyika became Independent. This transition, similarly, was followed by another transitional period leading to the present in which it serves as a church music tradition. It is anticipated that,if it continues as a living tradition, muheme may go through additional periods of transition, serving other social functions for the people of the Wagogo culture (Mapana, 2007).

Wagogo tribesmen gather for a circumcision ceremony. 1947. By George-Rodger

Of course, the transition of a cultural activity over a period of time causes a change in that activity. There is movement from one way of doing things to another, the second sharing at least some elements with the original (Tanner 1967). These transitions, clearly, are similar to other cultural transitions in life:the transition from adolescence to adulthood, the transition from unemployment to holding a paid position, and so on. Almost always, “change is the outcome of the transition” (Bascom 1959:25).

Wagogo people, African queens of drums

Traditions in African cultures, as with other cultures of the world, are always in transition. Kubik (1987) emphasizes that cultural traditions are not merely changing now, but perhaps from the moment they establish themselves as „traditions‟ have always been changing. Traditions change at different speeds and, Kubik adds, they have their own history, socio-cultural context and structure. He suggests, specifically, that music traditions change their form and structure in accordance with new emerging relationships, creating a different experience in the course of the transitions.

Wagogo drummer

When studying music that is going or has gone through a transition, understanding the original music tradition as much as possible is as important as understanding the tradition after changes have taken place. It is, however, also of great importance to comprehend the reasons for, and type of transition that has taken place.

Wagogo dancer. courtesy Martin Neil

Functional change of muheme

The main factor to have been influenced the functional changes of muheme from initiation to secular muheme appears to be a call by the Tanzanian government to revive and preserve Tanzanian culture. This call was made immediately after Independence (1961) by then President Julius KambarageNyerere. Mbuguni (1974) quotes Nyerere as saying “I believe that culture is the essence and spirit of any nation. A country which lacks its own culture is no more than a collection of people without the spirit which makes them a nation, Of all the crimes of colonialism, there is none worse than the attempts to make us believe we had no indigenous culture of our own or what we did have was worthless-something we should be ashamed of rather than a source of pride. Some of us, particularly those of us who have acquired a European type of education, set ourselves out to prove to our colonial rulers that we had become „civilized‟. And by that we meant that we had abandoned everything with our own past and learnt to imitate only European ways(p.16-17).

Msafiri Zawose is renowned for his traditional Gogo style music, which relies heavily on the zeze & limba in combination with distinct lyrical harmonies. This rich musical tradition is from the Wagogo people Dodoma in Central Tanzania. Msafiri Zawose, son of the late Dr. Hukwe Zawose, continues this musical tradition while fusing with more modern styles, creating a truly distinct and unique sound

Of course, Nyerere was using the term „nation‟ in a way the colonials were, and was not reflecting an African perspective on the socio-cultural/political unit represented by (then) Tanganyika. That issue, however, is beyond the scope of this paper. Nyerere continued by saying that “I have set up this new Ministry to help us regain our pride in our own culture. I want it to seek out the best of the traditions and the customs of all our tribes and make them a part of our national culture”(p.17).This was reinforced in 1995 by the Prime Minister Rashid Kawawa in 1995 who said that “the main objective of national culture is the development of Tanzanian nationalism and personality through the promotion of our own cultural activities” (p.17).

Young school kids thrilled the crowd with a 15min Tanzanian dance.

Many ethnic groups in Tanzania responded to Nyerere‟s call by performing some traditional music genres which were brought forward outside their socio-cultural contexts. Some ritualistic or function-specific traditions were adopted for secular occasions. Muheme was one of these, as Mchoya Malogo suggests:

Tulianzakuchezangomazamuhemezakisiasa (utamaduni) mwaka 1966. Tulichezawakatiwakuwakaribishawageniwakisiasa, kwenyemikutanoyahadharanawakatimwinginetulichezambeleyawagenirasmi

Our group started playing secular muheme in 1966. We played to welcome political leaders at political meetings; sometimes we even played in front of presidents (M. Malogo, personal communication, October 17, 2006).

The Zawose Family (Tanzania) aims to continue the legacy of Hukwe Zawose, one of the World's Music stars. http://canvas-of-light.blogspot.com/

Social functions of secular muheme

Since that time, the use of the muheme music tradition among the Wagogo of the Dodoma region can be found in political contexts, education, mobilization of the population and entertainment. The basic social functions of secular muheme became:

To raise challenges among the groups

In order to promote Wagogo music, competitions were held annually. This encouraged groups to compose special songs, some praising themselves as singers who were better than others. These kinds of songs helped to create challenges among the groups, hence, each group in every corner of Nyaugogo was active. However, according to a recent interview with Mchoya Malogo, “These days competitions are not organized because there is less interest in such things from members of the society, youth in particular” (M. Malogo, personal communication, October 17, 2006).

To create support for political campaigns

Muheme music was and is used during political campaigns to encourage people to attend political meetings and support a political party. The Nyereremuheme group from Chamwino village has supported the Chama Cha Mapinduzi party. During elections, the group has always been used by the CCM for their campaigns in different areas in Tanzania. It is believed that using the muheme songs create unity among people.

The transition of the muhememusic tradition from political usage to the church began to gain popularity in the 1998 when the government banned female circumcision in Tanzania (Mapana 2007).

Social functions of the muheme music tradition in the Anglican Diocese of Central Tanganyika, Dodoma.

Early missionaries held the musical traditions of the Wagogo in very low esteem. Peterson (2006:1008) found the following: “In 1898, Miss Pickthall adopted an infant she named Hephzibah. When the girl married a teacher in 1912, Pickthall organized a church wedding and taught local villagers to sing “a very pretty Welsh tune…[which is] to take the place of every objectionable song that they have hitherto sung in their own villages on such occasions”(p.1008).

The fourth Bishop of the Anglican Church of Central Tanganyika, Bishop Madinda, was the first Tanzanian Mgogo diocesan bishop to give emphasis to the intergration of Wagogo music traditions in church services (Mapana, 2007). Muheme, in this case, was a priority. Muheme in the church is believed to serve a number of social functions. Muheme

Wagogo people performing a dance. courtesy Martin Neil

A tool for encouraging people to join the church

In this section there are two sub-factors that were mentioned by Wagogo who were interviewed. First, many people join the church because the church has permitted traditional music to be performed in the church. During one concert, the by then Assistant Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Central Tanganyika, Bishop Kusenha, addressed the audience in Chamwino village, pointing out some historical facts. From the earliest days of the Anglican Church in Tanganyika in the late 1800s through the 1960s the number of churchgoers in the Anglican Church in Dodoma increased slowly. From 1970s to 1990s, however, the number of churchgoers increased more rapidly. This, Kusenha believed, was because the Anglican Church began using indigenous music traditions in the church.

Wagogo elder with thumb piano. courtesy Martin Neil

Second, after female circumcision was abandoned by the Government in 1998, many muheme adherents joined the church because the music was already in the church. It has been also noted that this music is a cultural cornerstone among Wagogo women. Many women appear to have joined the church because of the use of muheme music. This was strongly supported by the Assistant Bishop when he said:

Hatakamakikongweatapitabarabarani, akisikiangomayamuhemeinaliakanisani, lazimaatageukanakujakuisikiliza,

nahivyondivyoataanzakuzoeakanisakidogokidogonakuhamia

If it happens that an old woman passes by the church and hears muhemein the church, she must turn back and follow where the drums are, then slowly she can join the church (A. Kusenha, personal communication, February 13, 2005).

Adds beauty to the church service and makes the service active

This is accomplished through performance of different sections of muheme at different points in the church service. This includes introducing the church service, welcoming the preacher, singing during thanksgiving and ending the service.

Wagogo elder dancing to drum beats. courtesy Martin Neil

To remind people in the church of their sins

Elia Malebeto, a church catechist, said:

Mlimomuwaha wan g`omaazinikuwakukwegawanhunanyimbozonowakwimbazikuwahomelelawanhuwubiwaowamnhumbula, au zikuwakumbucizawubiwao we hayohayo,

nyimbozikuwafundawanhuwampitucilemulungu.

The muheme songs serve a major function in the church in that the songs are used to remind people to stop their sins and turn back to God. If somebody is going against God‟s will, the songs remind him or her to stop following the devil. Therefore, songs are used to teach people to be obedient to God (E. Malebeto, personal communication, October 18, 2006).

Other factors that led to changes in social functions from secular uses of muhemeto its appearance in the church include:

Wagogo elder: courtesy Martin Neil

Cultural awareness of the Wagogo

As the Wagogo have realized that the use of their own music in church is not sinful, the use of muheme in the church among the Anglicans of the Diocese of Central Tanganyika has become widely accepted. People are now free to use their own traditions to bring them closer to God:

Hukonyumawatuwalikuwawanazikataangomahizi, lakinibaadayewalianzakujiuliza

mbonatunatumiautamaduniwakizungukuabudu, nakwaninitusitumieutamaduniwetu?

Tulipogunduahilo, watuwalianzakutumiangomahizimpakasasa.

themselves: why are we using the European way of worship, and why don‟t we use our own traditions for worshipping? After that realization, the muheme drums started being employed in the church up to this moment. (I. Msulwa, personal communication, October 16, 2006).

Song texts are composed and sung to express the glory of God and to suggest ways in which the community should follow God‟s will. All compositions are based on biblical stories and general knowledge about the word of God.

Wagogo woman with baragumu horn. courtesy Martin Neil

Msafiri Zawose is a prominent Gogo musician from the Dodoma region of central Tanzania. He is the son of the late Dr. Hukwe Ubi Zawose, a world renowned performer of traditional Gogo music and dance.

Gogo music features a variety of instruments, including the limba, zeze, ndono, filimbi, and ngoma, all hand-made by the Zawose family in their family compound in Bagamoyo, Tanzania. Msafiri has followed closely in his father's footsteps and held on closely to the traditions of the Wagogo people as he continues his father's legacy with the spirit and passion of a new generation.

Explorer [Henry Morton Stanley in 1876] dancing with Wagogo people

Hukwe Zawose

0 comments:

Post a Comment