Ahmadou Babatoura Ahidjo, Nationalist, Pan-Africanist, freedom fighter and the first President of Cameroon

Ahmadou Babatoura Ahidjo (24 August 1924 – 30 November 1989) was Nationalist, Pan-Africanist, freedom fighter and the first President of Cameroon from 1960 until 1982. In 1947, when his country was yet a United Nations trust territory administered by the French, he won his first elected office, a seat in the Representative Assembly. He was then 23 years old. Sagacious beyond his years, quick-witted and persuasive in debate, he rose to become Prime Minister in 1958 and from this high office, guided his country to independence on the first day of January 1960.

President Ahidjo

He was one of the African leaders who spoke passionately in favor of stronger African unity. At the formation of Organization of African Unity at Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, Ahidjo was so happy that he exclaimed "Africa at last takes her place at the family table." He continued thus "The concept of Unity is unquestionably the noblest and most profound aspiration to permeate and animate our continent at the present time.

President John F. Kennedy visits with President of Cameroon, Ahmadou Ahidjo, and others upon President Ahidjo’s arrival at the White House for a luncheon in his honor. L-R: Naval Aide to President Kennedy, Captain Tazewell Shepard; US Chief of Protocol, Angier Biddle Duke; President Kennedy; President Ahidjo; Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs of Cameroon, Jean Faustin Betayene. North Portico, White House, Washington, D.C. Circa 13 March 1962 Photographer: Rowe, Abbie, 1905-1967.

In all the history of mankind, the original populations of Africa have been the longest subject to the Foreigner, humiliated, divided, exploited. And so, for them, any rehabilitation, their rehabilitation, can never be complete and total, until and unless they have made good this tragic period of division imposed by colonial conquests. The simple proof of this is that this aspiration towards Unity has featured and continues to feature in the programmes of all African nationalist parties who have fought or are still fighting for the liberation of their territory."

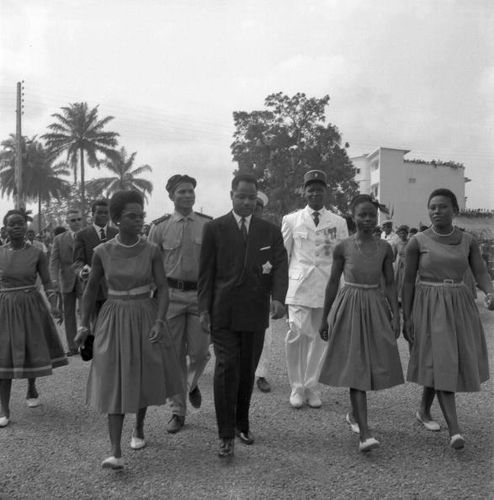

President Ahidjo walking with Cameroonian ladies during Cameroons independence celebration in 1960

"Elected President of the new republic at age 36, he withstood with striking courage the terrorist activities which threatened his government. In 1961, the former Southern Cameroun joined with the Republic of Cameroun to form the Federal Republic of Cameroun, a union which gave further diversity to a people whose ethnic and linguistic composition already has the most complicated in all of Africa. But with characteristic courage, and statesmanship of a high order, he met the challenge, and to this new nation of 4,000.000 he has brought stability and direction."

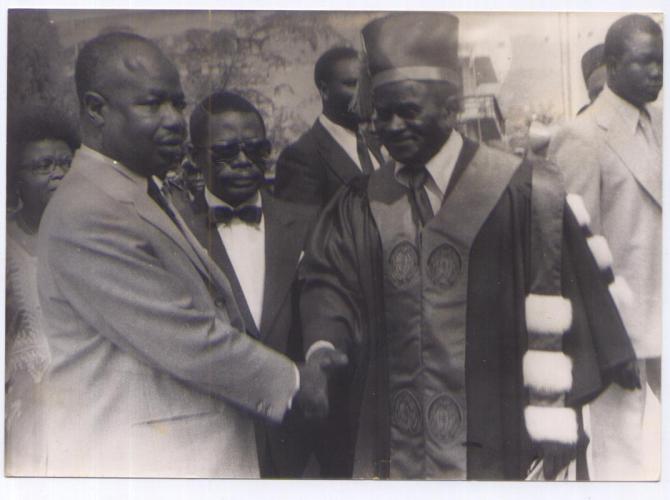

President Ahidjo Receives Honorary Doctorate (Doctor of Laws Honoris Causa) from Long Island University in New York. Circa March 16, 1962

Ahidjo`s ability in creating a single state by bringing together two federated states and the consolidation of power in the hands of one person- president ensured that the numerous ethnic groups in his country had equitable distribution and allocation of national resources and development.

President Ahidjo and his ministers after 1970 elections.

Ahidjo was born in Garoua, a major river port along the Benue River in northern Cameroun, which was at the time a French mandate territory. His father was a Fulani village chief, while his mother was a Fulani of slave descent.

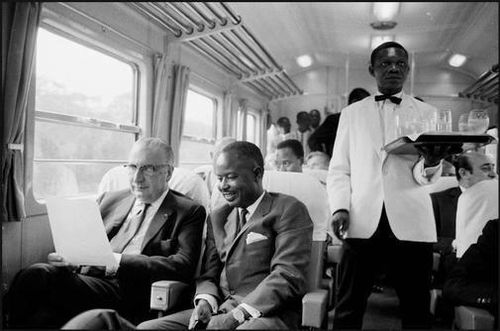

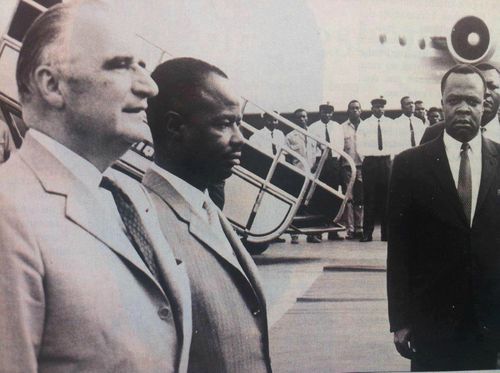

President Ahidjo of Cameroon sitting with the French president Pompidou in Cameroun

In 1942, Ahidjo joined the civil service as a radio operator for a postal service. As part of his job, he worked on assignments in several major cities throughout the country, such as Douala, Ngaoundéré, Bertoua, and Mokolo. According to his official biographer, Ahidjo was the first civil servant from northern Cameroun to work in the southern areas of the territory.

Ahidjo and Mbida, Circa 1958

His experiences throughout the country were, according to Harvey Glickman, professor emeritus of political science at Haverford College and scholar of African politics, responsible for fostering his sense of national identity and provided him the sagacity to handle the problems of governing a multi-ethnic state.

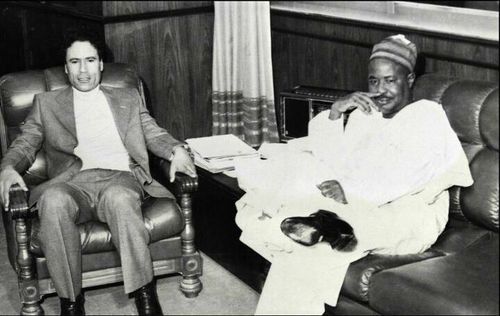

Ahidjo and Muamar Al Gaddafi

In 1946, Ahidjo entered territorial politics. From January 28, 1957 to May 10, 1957, Ahidjo served as President of the Legislative Assembly of Cameroon. In the same year he became Deputy Prime Minister in de facto head of state André-Marie Mbida's government. Upon independence in 1960, Ahidjo, as leader of the Cameroon Union, was elected as President, and he persuaded part of British Cameroon to join his country. He was reelected in 1965, 1970, 1975 and 1980, gradually establishing the complete dominance of his own party and outlawing all others in 1976.

He experienced a rebellion in the 1960s from a group known as the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon, but defeated it by 1970. In the early 1970s he created an unpopular constitution which ended the autonomy of British Cameroon and established unitary rule. Though many of his actions were dictatorial, his country became one of the most stable in Africa. He was considered to be more conservative and less charismatic than most post-colonial African leaders, but his policies allowed Cameroon to attain comparative prosperity.

Ahidjo resigned, ostensibly for health reasons, on 4 November 1982 (there are many theories surrounding the resignation; it is generally believed that his French doctor "tricked" Ahidjo about his health) and was succeeded by Prime Minister Paul Biya two days later. That he stepped down in favor of Biya, a Christian from the south and not a Muslim from the north like himself, was considered surprising. Ahidjo's ultimate intentions are unclear; it is possible that he intended to return to the presidency at a later point when his health improved, and another possibility is that he intended for Maigari Bello Bouba, a fellow Muslim from the north who succeeded Biya as Prime Minister, to be his eventual successor as President, with Biya in effectively a caretaker role. Although the Central Committee of the ruling Cameroon National Union (CNU) urged Ahidjo to remain President, he declined to do so, but he did agree to remain as the President of the CNU.

Paul Biya, vice-president and President Ahidjo

However, he also arranged for Biya to become the CNU Vice-President and handle party affairs in his absence. Additionally, in January 1983, Ahidjo travelled across the country in a tour in support of Biya.

Later in 1983, a major feud developed between Ahidjo and Biya. On July 19, 1983, Ahidjo went into exile in France, and Biya began removing Ahidjo's supporters from positions of power and eliminating symbols of his authority, replacing Ahidjo's portraits with his own and removing Ahidjo's name from the anthem of the CNU.

CAMEROON. Yaoundé. Presidential elections. 1970. President of Cameroon Ahmadou Babatoura AHIDJO. Saturday 28th March, 1970. by © Guy Le Querrec

On August 22, Biya announced that a plot allegedly involving Ahidjo had been uncovered. For his part, Ahidjo severely criticized Biya, alleging that Biya was abusing his power, that he lived in fear of plots against him, and that he was a threat to national unity. The two were unable to reconcile despite the efforts of several foreign leaders, and Ahidjo announced on August 27 that he was resigning as head of the CNU. In exile, Ahidjo was sentenced to death in absentia in February 1984, along with two others, for participation in the June 1983 coup plot, although Biya commuted the sentence to life in prison. Ahidjo denied involvement in the plot. A violent but unsuccessful coup attempt in April 1984 was also widely believed to have been orchestrated by Ahidjo.

President John F. Kennedy attends arrival ceremonies for President of Cameroon, Ahmadou Ahidjo. Standing on reviewing platform (L-R): President Ahidjo; President Kennedy; US Ambassador to Cameroon, Leland Barrows; Cameroonian Ambassador to the United States, Jacques Kuoh Moukouri. Ambassador of Nicaragua and Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, Dr. Guillermo Sevilla-Sacasa, stands at far left of image; Aide-de-Camp to President Ahidjo, Lieutenant Belladji Ngoura (partially hidden behind President Ahidjo), stands behind platform at left. Military Air Transport Service (MATS) Terminal, Washington National Airport, Washington, D.C. Circa 13 March 1962 Photographer: Knudsen, Robert L. (Robert LeRoy), 1929-1989

In his remaining years, Ahidjo divided his time between France and Senegal. He died of a heart attack in Dakar on 30 November 1989 and was buried there. He was officially rehabilitated by a law in December 1991. Biya said on 30 October 2007 that the matter of returning Ahidjo's remains to Cameroon was "a family affair". An agreement on returning Ahidjo's remains was reached in June 2009, and it was expected that they would be returned in 2010. There is a stadium named after Ahidjo in Yaoundé.

President Ahidjo

Few images remain of President Ahmadou Ahidjo, and it is often said that the Biya regime made an active effort to erase any visual or audio references to Cameroon's first head of state. The few surviving pieces of archival footage of Cameroon in the period following independence will likely come to light after Biya's departure

Source:

His Excellency Ahmadou Ahidjo, President of the Federal Republic of Cameroun`s epoch-making speech at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on the Formation of OAU

“Africa at last takes her place at the family table”

Ahmadu Ahidjo

Your Imperial Majesty,

I wish to welcome your guests who have journeyed from all the horizons of Africa and no doubt to be worthy attendees of this historical gathering, Addis Ababa and all the glorious Ethiopian people whom you incarnate, are adorned with the purest and most legendary hospitality.

You have welcomed us all, many as we are, such as we are, with an open heart and open arms.

Permit me to follow the other distinguished Heads of State, to express to you our deep feelings for this warm welcome and say how grateful our people, whose good tidings we bear, will be to yours for the agreeable stay and friendly we spent on your soil.

Your Excellences,

We have come to this extraordinary meeting in Addis Ababa with the conviction that it must and will mark a major decisive stage in our march towards freedom and the building of African Unity.

The concept of Unity is unquestionably the noblest and most profound aspiration to permeate and animate our continent at the present time. In all the history of mankind, the original populations of Africa have been the longest subject to the Foreigner, humiliated, divided, exploited. And so, for them, any rehabilitation, their rehabilitation, can never be complete and total, until and unless they have made good this tragic period of division imposed by colonial conquests. The simple proof of this is that this aspiration towards Unity has featured and continues to feature in the programmes of all African nationalist parties who have fought or are still fighting for the liberation of their territory.

President Ahidjo`s wife, Germaine Ahidjo. Circa 1963

This demand has been widespread and still is, to such an extent that it has become a challenge on a continental scale, which history obliges us to accept. We cannot logically denounce the Foreigner for having divided us, nor can we continue to complain of this division if, once having become masters of our destiny, we prove ourselves incapable of restoring this Unity.

To these sentimental reasons must be added others more pressing challenges, imposed by the economy, by technique and policy, in short, by the present trends in world affairs.

Is it therefore a mere accident that the two greatest world powers of today, Continental China and India apart, are also the two largest human concentrations and as a result of industrial and technical potential? Who could deny that world affairs are influenced, whether we like it or not, by this powerful China with its 650 million inhabitants? Is it by chance that Europe herself, conscious of and surprised by the astonishing successes of our era which are beginning to elude her, has now, after a voluntary self-appraisal embarked upon a feverish work of construction which is underway despite its own problems?

Accordingly, sentiment, reason, self-interest and in the final analysis survival, impel Africa to unite if she wishes her voice to be heard in the councils which will determine our planet’s fate.

Defining this objective, is to grasp ipso facto the importance of what is at stake, become aware of the complex nature of the real facts behind the Africa of today and to all intents and purposes take stock of the difficulties to be overcome if our ideal is to succeed and to triumph.

We must firstly, as Africans, make an appraisal of this Africa on the march. We must realize the road travelled in the recovered freedom, and then keep in step together, over the remaining distance to be covered, which will be the determining factor in our progress in this presently dangerous world, dangerous because it is so full of pitfalls.

U.S. President Ronald Reagan and President of Cameroon Ahmadou Babatoura Ahidjo. Date 26 July 1982

We must take the indispensable precautions for ensuring every chance of initial success. We must, as is always the case with Africans, open our hearts in frank, loyal and brotherly discussion. We must obtain the complete support of all concerned, free from any thought of ulterior motive, of any distrust, that deadly poison which corrodes any and every organization.

It is, I feel persuaded, no betrayal of our ideal of unity to say regretfully that the Africa of today, once so united in its determination to be free, reveals its divisions to the entire world; at least in the now free territories. There is no escaping the fact that such schisms, even if not necessarily hostile, have tended to diminish our following and have saddened our friends, those who had faith in us and hoped that our appearance on the international scene would bring in its wake, together with the seal of our solid union, the message of a new world where hatred and opposition do not exist, where friendship and love are cultivated.

At this juncture, it is only natural - and I hope you will allow me to do so briefly - to take a look at our present relations.

No plan for African construction can be envisaged, however brief, whilst, alongside of us, next door to ourselves, other Africans, our brothers, are still whimpering under the yoke of the most backward type of colonialism, its back to the wall, profiting from the collusion of those who do not forgive history for taking its normal course.

How can one finally talk about African Unity without a thought for the southernmost corner of our continent where one of the most saddening tragedies imaginable is being played out? Whilst the conscience of the entire world is involved in this, and constitutes a challenge to human rights, it is above all a nameless disgrace and insult to the dignity all Africa's sons.

But in actual fact, how do we appear to the world? In spite of a strained will to unite, how different are we really! Differing cultures bequeathed by our former colonial rulers, each State differing in the way it obtained its freedom, differing in its economic structure or in the institutional organization of our Nations. Differing also in the various friendships we have made which cannot help but influence our behaviour or our way of viewing things.

CAMEROON. Yaoundé. State visit. French President Georges POMPIDOU discussing with the Cameroonian President Ahmadou AHIDJO during a reception in the presidential palace, on his first official trip to Africa. February 9th, 1971. by © Guy Le Querrec

As is normally in such cases, we have had different approaches to the fundamental problems of the hour; we have had an imperfect or incorrect vision of the internal situation of our neighbours. We have even had on occasions misunderstandings. We have also been impatient or too eager to help, for right or wrong reasons.

In short, all these factors have estranged us from this basic virtue we call tolerance, without which neither cohabitation nor cooperation are possible.

The hard facts of today’s Africa oblige us therefore to accept each other as we are, to keep this firmly in mind and try to understand each other.

Raising such questions, even in this prefatory manner for which I ask your indulgences is to touch upon the essential problems involved.

The principle of political unity is a concept that is both precise and wide-ranging which, in actual fact, cloaks various realities. It can be anything from the institutional type to simple joint consultation and including treaty arrangements. Apart from this, in such matters, we have the need for all our intelligence, vigilance and caution. In no other sphere do we so much need to beware of the haste and enthusiasm which are the natural products of our present comradely gatherings.

Modern Africa has after all provided us with a wide range of experiences for some years now, as differing as they are also instructive, either of groups of purely African States on regional basis, or of African States with other non-African States. Our continent is in fact traversing at the present time a period of intense growth. In deciding once and for all to construct this Unity, let us give this evolution the chance to work and preserve our peoples from the unavoidably baneful consequences of acts which, even though inspired by our good will, could be traumas to the normal progress of such evolutions. Nature and events are stubborn: they do not easily yield to outside disturbances without difficulty.

We must view things on a larger scale, taking in everything of a similar nature that is being undertaken on our planet. Precedents abound. An intelligent inspiration which cannot harm the originality to which we are so deeply attached and which we have to offer to the world. Agreed as we are upon the fundamentals the question remains of the form to be given to our Unity.

Firstly and above all things, basic alternatives are involved. We must choose between political principles, we must also choose between economic policies. In more technical fields, cooperation appears simpler.

Now, to be realistic vis-à-vis the political aspect that Africa presents, which I have just sketched in, the organization that we can give to African Unity has to be a highly flexible one.

It seems to us that any rigid form of institution would be premature at this stage. And so, for the moment, let us have neither Federation nor Confederation. In our opinion, this will involve making a complete break with everything presently existing.

What has to be immediately institutionalized is the periodical meeting of all the African Heads of State. Its task would be to weigh up experiences, decide upon alternatives, harmonize our policies, standardize decisions made on the main affairs of continental importance or which require a common stand to be taken before international opinion. Naturally, set up as it would be for Africa and Africans, this Conference would only comprise Heads of State of African Governments.

The proof of such Unity would primarily consist in the demonstration of our foreign action, and especially in the international forums. It follows that, once the stand we take in summit conferences is coordinated and agreed upon, we have to set up on an official basis, institutional if necessary, the African groups which are often formed solely for consultative purposes within the different international bodies, inside UN, specialized or other organizations.

But once again, if all this is to be durable, we have to agree upon certain basic principles. We must accept each other for what we are. We must recognize the equality of all our States, whatever they be and whatever their size or population; we must accept the sovereignty of each and every one, its absolute right to exist as a sovereign state in accordance with the will of its people. This implies absolute respect for one's neighbour; this implies abstaining from intervention in its internal affairs from encouraging or trying to maintain covert or overt subversion.

Even more on the economic than the political level, African Unity will be our salvation. In the face of the activities of the combined and gigantic concentrations that exist these days or are being established, which of our countries is capable of defending its interests unaided? Dependent in general upon fluctuations in world prices, our economies are struggling up the arduous slope of development and industrialization. The realization that we are amongst the outcasts of what we call the developing uncommitted nations is to bring more than ever home the need for us to be organized and united.

It is obvious that the sum total of our products, primary as they may be, constitute a considerable part of the total world consumption and that the voice of a group like ourselves will have a different ring and carry a different weight.

Ahmadu Ahidjo

Admittedly, I am not forgetting that certain of our States have already started to set up on a purely regional basis organizations of an economic nature.

Nor am I forgetting that a number of us who have subscribed to an Association with extra-African economic organizations recognize the short-term benefits to be derived in the initial stages which are particularly critical for our economy.

This is not the place where we wish to indicate our policies.

The truth is that we have to plan ahead and take a long term perspective. We are convinced that the different experiences in this field, as in any other, are only stages on the arduous and difficult path, the end of which we shall only attain after patient efforts. What we need is perseverance starting by broadening and harmonizing the concentric circles already existing. We have to attain the ultimate stage.

In this field, Africa, unlike similar experiments that have been launched elsewhere, is well placed. It is only at the beginning of its industrialization. It can accordingly at one stroke avoid the pitfalls incurred by sacrifices, difficult to accept, requiring us to renounce specific trade routes or markets which have to date been closed or protected. On the contrary, coordination in our plans for development can assist States to specialize in industrial production and avoid, within the same economic area that has been created, the installation of competitive activities.

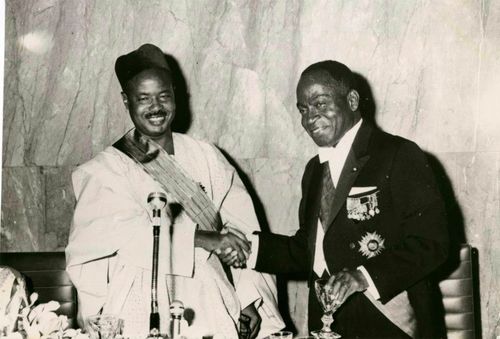

President Ahidjo shaking hands with Prof. Victor Anomah Ngu

All of this postulates cooperation between the existing regional unions and the development of economic activities to the scale of a continental. This implies above all a change in attitude and the determination to obtain, here, amongst ourselves and on better conditions what we frequently import from abroad on unfavourable terms of trade.

Experience has proved how difficult it is to achieve a rapid political integration. And so, in order to keep open the possibilities of such an organization for economic cooperation, the latter could be embodied in a separate treaty.

Inspite of the outposts still remaining here and there, decolonization has won the day. Now we embark upon another great battle which will leave its mark upon the second half of the 20th century: the economic liberation of the developing countries of the uncommitted world.

This is precisely what was realized by the 17th Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations when it turned its attention to the possibilities of an International Conference on Trade. It is only natural therefore that Africa should also mobilize and prepare her forces: truly, she has a lot at stake.

Our continent can claim that it has made a major contribution to the prosperity of the world, not only with its raw materials but with the sweat and blood of its sons, enriching other parts of the world where colossal fortunes and gigantic agricultural and industrial powers have since been built up.

What we are claiming now is not an illusory and impossible redress of the past, but a fair remuneration for our primary products and the stabilization of prices. What we demand is a readjustment of the terms of trade which are only detrimental to one side, ourselves. It has got to be understood - in agreement moreover with our other partners amongst the developing nations - that we are determined no longer to let this state of affairs continue unchallenged.

Finally, this era in which we live has shown that our relations, in spite of our good will and desire for unity, have not always been unclouded. This organization we shall have set up would be quickly threatened by disintegration if it does not at the same time provide the machinery for settling the differences which can arise amongst its members. There are examples in this sphere upon which we can draw to our mutual benefit.

Ahmadou AHIDJO (debout), president of Cameroon, President of the French republic Georges POMPIDOU and Jacques FOCCART, General Secretary for the African communities and for African & Madagascar Affairs. On the left, Yvon BOURGES secretary of foreign affairs. Mercredi 10 février 1971. by © Guy Le Querrec

Judicial bodies are already in existence, such as the International Court of which our States are members. A Conciliation Commission could be set up to take cognisance of our internal disputes and give an initial ruling.

Differences which the Conciliation Commission has been unable to settle would be brought before the International Court of Justice at The Hague.

There also remains the matter of cooperation in spheres other than the political and economic ones which I have just touched upon. There exist within the groups already installed specialised organisations for defence, transport or telecommunications. Failing a merger of these which at the present time seems difficult or simply premature, we could envisage a periodical consultation between management or execution boards so as to achieve subsequent harmonisation and unity.

In this way, we shall initiate in all fields a close and progressive cooperation amongst ourselves, slow but effectual, towards the achievement of a Unity. This will have solid foundations since it will have given the time for the different experiments in progress to mature and come to fruition, unaided these would lead to the inevitable table of destiny.

Your Excellences,

There are two schools of thought, springing out of one civilisation that has been stamped with the hardness of steel by out and out mechanisation, are gripping the world like the two inexorable jaws of a vice, threatening to asphyxiate it; nay, pound it, pulverise it even… Does not the entire earth live at present in perpetual fear at the sight of this sky glowing with the ominous flashes that announce that, the total annihilation, is henceforth within the reach of man and his whims? What a strange irony, that matter, which suddenly discloses to us, by dint of our struggle to disintegrate it, that we are imperceptibly sliding down the slope of our own self-destruction.

That is why Africa must testify before world opinion. That is why the voice of Africa has got to be heard, the voice which proclaims in appealing tones its love for mankind, which reminds us that the finest emotion on earth is not simply that aroused by the clash of arms.

After much suffering, effort and patience, Africa at last takes her place at the family table. It is the time to record our regret that empty seats await those who are still detained be the Foreigner.

But we are already filled with hope by the conviction that soon they will be present besides us and with us to build Africa, our motherland.

May God enlighten us all, and may the fruits of our work be such that they are hailed be the generations to come as a major contribution to the building of a world in which our continent shall have its select and rightful place.

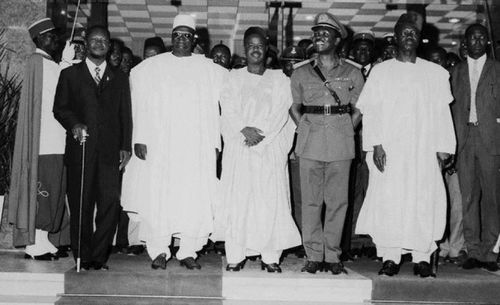

On December 6, 1973 Yaounde - Heads of state of five African nations to meet the Chat Lake Chad. L to R: Jean Bedel Bokassa of CAR, Niger's Hamani Diori; Ahidjo, General Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria and Chad's Tombalbaye - in Yaoundé, Centre.

REUNIFICATION AND POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM IN THE MAKING OF CAMEROON'S INDEPENDENCE

Martin Z. Njeuma

Introduction

Effective occupation of British Cameroon by British authority required a form of governance with which the Cameroonians would comply willingly, rather than coercively. This imperative led to the indigenization of the colonial state through the adoption of the system of indirect rule. The post-colonial state, too, embraced indirect rule, albeit in a modified form. A corollary of this process of colonial and post-colonial state construction has been a redefinition of power relations at state level. It has also had significant repercussions at the material level. This paper is a study of indirect rule in the North-West Province of Cameroon. The present analysis adopts a multidisciplinary approach focusing on questions of political economy, which complements E.M. Chilver's analysis of indirect rule in the same region between 1902 and 1954 (1963).

Since 1916 when the British and French partitioned German Kamerun, the reunification of Cameroon has been an important political issue. In modern times many politicians have risen and fallen depending on their skill in handling the implications of reunification. The point is that the very survival of Cameroon, in terms of national integration and harmonious development, depends largely on a profound understanding of the role that the quest for reunification has played in Cameroon's political history. The history of the reunification movement has been recounted elsewhere from many perspectives (Ardener 1967; Johnson 1970; Kofele-Kale 1980; Bayart 1989). It is the purpose of this paper to highlight how reunification affected the development of an independent Cameroon. A major hypothesis is that reunification conditioned how the principal political actors perceived independence.

Already by 1894 the Treaties setting up the entire international frontier of German Kamerun had been signed with Britain and France respectively (Hertslet 1967; Rudin 1938). However, the political configuration of Kamerun changed suddenly between 1914 and 1916 when the allied forces of Britain and France, with assistance from the Belgians, ousted the Germans and partitioned the country. The partition Treaty gave Britain one quarter and France three quarters of the territory and inhabitants, including the important towns of Douala, Kribi, Garoua and Yaoundé. This fact, from the start, made French influence preponderant in Cameroon.

Reunification was a desire to return to the German territorial frontiers before the First World War. This desire varied in strength from one part of the country to the other (Fanso 1982). In the predominantly Moslem north no local and self-sustaining movement emerged to fight for reunification. There was little interest in reunification because religious and linguistic solidarity over a wide area bred permissive habits towards frontier regulations. In contrast, the struggle for reunification was strongest in West Cameroon and the adjacent French territories because the European powers were keen to protect European investment and sources of revenue in the region against native traders who ignored the frontier restrictions.

The campaigns for reunification were interlinked with those for independence but there were essential differences in final objectives. For example, as a slogan to win political support at the United Nations (UN) and mobilise the masses in Cameroon, reunification overshadowed both the demand and the education for independence. Thus the notions of personal liberty, political democracy, national freedom, cultural self-expression and economic development, which were ideas concomitant with independence, received less attention. To begin with, reunification was advanced as a solution to irksome frontier restrictions and harassments which disorganised traditional activities in the political, economic and cultural fields. For this reason, the Anglo-French frontier presented a significant target for the primary resistance movements. By far the strongest challenge to the frontier's existence was the imperative to remain Cameroonian and to restore the full Cameroonian identity even under a system of dual governance. During the mandate period some attempts were made to assuage the ill-effects of the frontier on the population in both forest and savannah regions, but these did not go far enough to reduce the cry against a divided Cameroon.

The Cameroonian voices for change became organised after the Second World War when the European powers, Britain and France in particular, accepted the principle of transfer of power to Cameroonians. This decision set the stage for several Cameroonian leaders to emerge and distinguish themselves by forming political parties. There was little that was original in their actions as they were either imitating or being prompted by politicians in the metropolitan countries. The raison d'être of these parties was simply to compete with one another to replace the outgoing colonial rulers. A sort of free-for-all political careerism was installed.

Georges POMPIDOU and Ahmadou AHIDJO, president of Cameroun.

Behind Pompidou: Jacques FOCCART, General Secretary for the African communities and for African & Madagascar Affairs. Mercredi 10 février 1971. by © Guy Le Querrec

Political consciousness had not developed evenly all over the country but had its fullest impact around the capital, Yaoundé, and the coastal regions where the Douala peoples were prominent. Initially, rapid progress in political participation came to rely greatly on Douala elite leadership (Derrick 1989) which had demonstrated great political astuteness in the face of large-scale German expropriation of land. The Douala first entered contemporary politics before the Second World War, as members of the Jeunesse Camerounaise Française (Jeucafra) in response to Hitler's bid to regain Germany's colonial empire. At that time the French authorities sponsored Soppo Priso to lead Jeucafra (Joseph 1975; Zang-Atangana 1989: 75).

However, when the German threat was over and Jeucafra dissolved, Soppo Priso turned around to demand liberty and human dignity for all Cameroonians. He was aware that the degree of suppression of political liberties under colonial rule was such that the French authorities would not tolerate unwelcome political actions. Recourse to the issue of reunification seemed the most convenient strategy that camouflaged his real ambitions. He was familiar with how the issue of reunification among the Ewe in Togoland had been favourably received at the United Nations Councils, had drawn attention to, and advanced, the territory politically. Since Cameroon was not legally a colony but a trust territory of the UN, he put forward reunification as the cornerstone of his newly formed party, the Rassemblement Camerounais (Racam) in 1947 (Zang-Atangana 1989: 78).

In doing so, Soppo Priso hoped to locate the legal battlefield outside Cameroon, in the UN He used the UN to challenge French assimilation policies in Cameroon in light of the strong anti-colonial lobbies in that world body (Gardinier 1963). However, the stumbling block was the Cold War that polarised political views (see Langhëë in this volume). Though relatively moderate in its general political orientation vis à vis France, Racam was considered revolutionary.

However, the UN had little effective power, and the Council of the Trusteeship held that it could only make recommendations to the administering powers and could not oblige them to obey its decisions. Indeed the danger was that since the issues of Cameroon's political development could not be settled directly in the UN, in Cameroon itself the bid for reunification fell into the category of revolutionary politics and anti-French activities. As expected, the proponents came under heavy intelligence surveillance, and were to be combated and extirpated in the same way as communists.

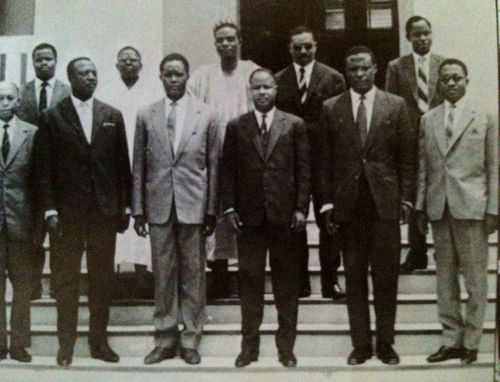

An early group picture of the Federal Government in 1962. Back row from left to right: Ekangaki Nzo (Foreign Affairs Deputy Min.), Jean Akassou (without portfolio), Sadio Daoudou (Armed Forces), Eteki Mboumoua (Education), and ET Egbe (Deputy Justice Min.). Front row from right to left: Victor Kanga (Economy), ST Muna (Transportation, Mining, P & T), Ahidjo (Head of State & Gov.), Charles Ako Awana (Territorial Admin, Finance), Betéyené (Foreign Affairs) and Simon Tchoungui (Health). - In Yaoundé.

However, the idea of reunification was differently expressed in East and West Cameroon in parallel with differences in concepts of independence or political change. In East Cameroon radical nationalism was ranged against the French and force was freely used. Reunification was a revolutionary idea and only radicals adhered to it. As the leading radical party, the successor party to Racam, the Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) took up the banner in 1948 with reunification high on its agenda (Joseph 1977; Um Nyobe 1989). It did not, however, define or give any content to reunification but assumed that its audience had a common understanding of its message. In West Cameroon the bogey was Nigerian sub-imperialism; but in the early days at least, reunification was invoked to solve local problems and preceded the formation of locally based political parties.

In the political wake of the Second World War, the UPC's advocacy of 'immediate reunification' ought to be seen more as a strategy than as a programme of action. Firstly, as for Racam, it was a ploy to get the UN to allow reunification before independence, which would permit the party foremost in advocating that platform to carry the day in the struggle for power. Secondly, reunification was expected to neutralise both French and British influence in Cameroon to the territories' advantage. It was reckoned that the two powers would compete with each other for a new hegemony in a reunified Cameroon, and that the Cameroonians would be able to dictate their own terms of co-operation.

The UPC used the political arguments for reunification to establish common ground between politicians of East and West Cameroon. Furthermore, they ignored the international frontier and went ahead to campaign and win supporters for the UPC in West Cameroon (Um Nyobe 1989: 83-84; Joseph 1977: 188ff; Zang-Atangana 1989: 272). Such trans-frontier activities gave the party the reputation among the population of constituting the real opposition to colonialism. However, their strident criticism of the French provoked the French authorities to force the leading political figures to declare whether or not they wanted French participation in the development of Cameroon following independence (Joseph 1977: 248). As long as reunification remained the virtual monopoly of the UPC and was expressed in what were considered revolutionary terms, opponents of the UPC entrenched themselves in the French camp as an easy way of furthering their political careers.

As the 1960s approached, both French and British colonial diplomacy accepted that independence was inevitable and that France and Britain should seek to channel the independent States into structures such as the French Community and the British Commonwealth. Thus independence was gained but within the western capitalist alliance. This did not coincide with the UPC's vision of independence. The party distrusted an independence which depended on the goodwill of the colonial powers. The result was that the pursuit of reunification became entangled in a ruthless confrontation between the UPC and the colonial powers. The entire resources of the State were ranged against the UPC, reducing it to a shambles in less than two years. The fall of the UPC took the steam out of the reunification movement.

In West Cameroon reunification entered party politics as a result of political events in East Cameroon. The idea at first won adherents because populations were split by the frontier and also East Cameroonians were present in several principal towns. The latter had taken up permanent residence after the First World War or had emigrated to avoid the oppressive French indigénat system.

These migrants fell into two categories. The first were the German trained elites, mostly from the Douala and Yaoundé regions and residing in Buea, Tiko, Victoria and Kumba districts. An important link was R.J.K. Dibonge, a Douala by birth, who had served in both the German and French administrations. Retired in 1947, he returned to take up permanent residence in Buea in 1949. He proceeded to use his political experience to build support for reunification and to keep this issue in focus in West Cameroon. The second category was composed of traders, mostly Bamileke and Bamum. They exploited a dynamic commercial traffic across the frontier, a cardinal aspect of which was the existence of relatives and support systems on both sides of the frontier. One important figure was Joseph Ngu of Kumba, a successful businessman who used his wealth and influence to host meetings that promoted reunification and to keep up a stream of petitions to the UN. Both Dibonge and Ngu had been active in creating the French Cameroon Welfare Union which promoted the idea of reunification. This type of grassroots linkage strengthened trans-frontier ties. The idea spread through private initiatives, diffused and unstructured channels, and not through a political platform with a central source. Hence, its enemies could not easily kill it.

The foundation of the Cameroon National Federation (CNF) in 1949 by the West Cameroon political elite created a wider forum for the French Cameroonian Welfare Union to win support from the indigenes in the political struggle for reunification. However, despite formal commitment to reunification, the CNF focused more, if not entirely, on the internal issues of West Cameroon. Their leader, Endeley, for instance, saw a brighter future in pressing for workers' rights, representation in the Nigerian legislative organs and reform of the 'Land and Native Rights Ordinance' rather than in 'reduction of frontier difficulties'. This unclear stand on reunification led the 'French Cameroonian' activists to break away to form the Kamerun United National Congress (KUNC).

The KUNC was born in Kumba where popular political options centred around reunification. The new party combined anti-colonial demands with a dynamic stand on reunification. In light of the UPC support of these demands the KUNC welcomed the latter's financial and logistical support. However, while pushing reunification to the fore of West Cameroon politics, collaboration with UPC activists always bore the threat of a UPC takeover. As it was, the UPC members introduced new forms of patronage and authoritarian leadership that presaged new forms of domination.

If West Cameroonian politicians learned any lessons at all from the period 1948 to 1952 when the UPC was the chief promoter of reunification in both East and West Cameroon, it was that neither 'immediate reunification', nor merely 'reunification before independence', were in West Cameroon's long-term interests. This was reflected, for instance, in Mbile's about-turn in support of the further integration of West Cameroon into Nigeria. He founded the Kamerun People's Party (KPP) to fight an election on this platform. In 1953, the leading political figures in West Cameroon regrouped around Endeley's Kamerun National Congress party (KNC) and placed reunification as an ultimate but not an immediate goal. Indeed, the immediate goal was the antithesis of reunification, i.e. regional status within Nigeria. Rejection of reunification seemed to reach a peak after the KNC's resounding victory in the 1954 election in West Cameroon. However, the reaction was immediate and a substantial faction of the party broke away in 1955 to form a new party, the Kamerun National Democratic Party (KNDP). Its leader, John Foncha, brought reunification back onto the platform of mainstream West Cameroon politics.

Foncha, like the Fon of Bafut, envisaged East Cameroon as fire, because of the civil war that raged there, and Nigeria as water. He abhorred the violence in East Cameroon, but judged that it would be short-lived and that reunification would still be possible. He therefore built a broad political platform so that by the beginning of 1959, 'immediate reunification' as a slogan to mobilise the masses against imperialism had lost its savour. The UPC had been banned in West Cameroon and its successor, the One Kamerun Party (OK), had not been able to withstand the massive opposition to its policies on reunification. Reunification had been couched in revolutionary language, and represented a unfamiliar political culture to the average West Cameroonian whose attachment to the rule of law was strong. The UPC and OK leadership had wrongly thought that the West Cameroonians' lack of special attachment to France would bolster up their own efforts against France. Ironically, the closer East and West Cameroonians tried to work together, the more they were pushed apart by linguistic, cultural and political differences cultivated separately for over forty years under French and British rule.

1959 was a decisive point in the political history of French and English speaking Cameroons. In West Cameroon, Foncha defeated Endeley in the elections of January 1959, elections which were also a test of the popularity of Foncha's brand of reunification. In East Cameroon the government passed from André-Marie Mbida to Ahmadou Ahidjo, but without solving the problems of widespread terrorism and strong French involvement in the country's affairs. Reunification now depended on Foncha and Ahidjo but neither had been in at the outset of the idea; they had simply picked it up as a convenient slogan but had never bothered to work out a programme.

President John F. Kennedy meets with President of Cameroon, Ahmadou Ahidjo, and others in the Cabinet Room of the White House, Washington, D.C. L-R: Cameroonian Ambassador to the United States, Jacques Kuoh Moukouri; President Ahidjo; Minister of the National Economy of Cameroon, Victor Kanga; unidentified; US Ambassador to Cameroon, Leland Barrows; Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, G. Mennen “Soapy” Williams; Under Secretary of State, George Ball; President Kennedy; US State Department interpreter, Edmund S. Glenn; Deputy Director of the Office of West African and Malagasy Affairs, Donald Dumont. Circa 13 March 1962 Photographer: Rowe, Abbie, 1905-1967.

The imminent end of United Nations trusteeship in East Cameroon in January 1960 forced both leaders to consider reunification and give content to what had been merely an electioneering slogan. The nationalists in each State knew little or nothing of each other. They had faced different problems in their history. In these circumstances, each leader gave reunification a meaning appropriate to his own internal conditions and political goals. Ahidjo was never excited about reunification, and so played down its structural implications. His political programme dealt exclusively with East Cameroonian politics. But the one thing he did that made all things possible was to insulate reunification from party politics. This was achieved by getting the East Cameroon Assembly of Deputies to approve a motion in September 1958 accepting reunification with West Cameroon whenever the latter was ready (Ahidjo 1964). From this and other statements it can be seen that reunification was never an imposition from East Cameroon. In fact, Ahidjo and the East Cameroon population were largely indifferent to it because the ultimate form of independence of his part of Cameroon had already been decided by the end of 1958.

In West Cameroon, the political leadership was under great pressure to define reunification in concrete terms since reunification was at the top of the political agenda. However, this instead led to much tension and political polarisation. The dominant issues were on the one hand, association with Nigeria, advocated by Endeley's party with the tacit approval of the British authorities, and on the other hand, secession from Nigeria and reunification with East Cameroon advocated by Foncha's party. It was generally understood that the victor in the elections would proceed to negotiate the terms of union with either Nigerian or East Cameroonian leaders.

Foncha's party won the election by 14 to 12 seats, receiving over half the popular vote. Immediately several basic problems arose. Firstly, the victory gave the West Cameroon government the constitutional power to pursue reunification. Secondly, Endeley (and the British) ceased moves towards the further integration of West Cameroon into Nigeria. Indeed, reunification became for the first time a State to State affair. Foncha had fought the elections on a platform of secession from Nigeria and reunification with East Cameroon outside both the French Community and the British Commonwealth. He could, therefore, scarcely count on British co-operation. Moreover, the British authorities had expected Endeley to win the election in the belief that the West Cameroonian elite would rally to protect their British culture and values. When Foncha won, the British feared increased widespread hostilities and so they maintained close links with Endeley's opposition party in the hope that it would provide the necessary balance and, perhaps, actually make a come-back to power.

The British authorities decided to act fast to kill reunification and refused to sanction the 1959 election results. Foncha, they claimed, had won the elections on parochial and vague promises to the electorate. They observed that reunification had become so unpopular that none of the successful politicians had explicitly canvassed for reunification. Indeed, Foncha's party had ceased to advocate reunification in public and, instead, stressed secession from Nigeria followed by a period of trusteeship before independence. The British authorities could not hold another general election immediately. The democratic solution was to use the United Nations to organise plebiscites in the British Cameroons to determine the people's wishes on how to end British trusteeship. However, this went awry when the plebiscite limited the choice to gaining independence either by joining East Cameroon or by maintaining their connection with Nigeria (see Chem-Langhëë this volume).

Throughout 1959 British officials increased pressure on Foncha to abandon reunification. They organised several meetings in West Cameroon, Nigeria, Britain and the United Nations. Under the spell of the personalities of Endeley and Mbile, they minimised Foncha and failed to take cognisance of the soaring popularity of the KNDP after the 1959 elections, and Endeley's waning fortunes among the leading politicians. There were signs that Foncha was willing to abandon reunification provided that the British extended the period of trusteeship and stopped insisting on an even more unpopular option for West Cameroonians, the Nigerianisation of Cameroon. Nevertheless, the British employedmmuch arm-twisting at the UN to line up western and anti-communist representatives to block Foncha's bid to make secession the second question in the British-inspired plebiscite.

However, the more the British and Endeley tried to push Foncha towards immediate reunification, the more he resisted by, for example, imposing party discipline on his followers to win the plebiscite. A further effect was that Foncha drifted irretrievably into the hands of Ahidjo and his French allies. While this had been foreseen, what was not expected was that the people would follow Foncha. Foncha's dilemma was how to hold his constituency intact while winning support from Endeley's followers. Foncha's solution was to transform the concept of reunification into one of federation. At this time federation was an attractive catch-word which seemed to guarantee autonomous development in a unified Cameroon. Thus by unification Foncha meant a loose federation of States:

Pompidou`s visit 1971

Joining the Republic of Cameroon means federating with the Republic of Cameroon in a new federation to be formed immediately after the plebiscite. In this federation, the Republic of Cameroon and either the British Cameroons as a whole or Southern Cameroons will enter as members on equal terms... (Foncha to the Special Session of the House of Chiefs - Kamerun Times 22/12/1960.)

The new formula also bore the seeds of destruction for British policy in West Cameroon. It was a constitutional formula which was based on the principle that negotiations for a federal constitution were a matter for the ruling parties and eventually for the East and West Cameroon governments to work out the details. It claimed an equal voice for West Cameroon in the making of the 'new federation' while preserving the West Cameroon identity. The loose federation formula allayed the fears of the doubting West Cameroonians about the absorption of their State and people in reunified Cameroon. Under this system they felt they still had a chance to preserve their much valued British heritage and at the same time pursue West Cameroon's specific needs for independently attracting foreign aid for development.

However, the British, along with Endeley and his followers, did not perceive the potency of the federal formulation used by Foncha. Indeed, Mbile's and Endeley, as leaders of the Cameroon People's National Congress (CPNC), continued to fight a losing battle based on the earlier conception of reunification as an extremist and vague notion. The consequence of Endeley's weak campaign showing was that Foncha, as premier of West Cameroon, now felt confident to negotiate reunification, or the specifics of federation, with Ahidjo single-handed, without first seeking general consensus in his party, the KNDP, let alone amongst the population of West Cameroon.

However, the years 1960 and 1961 saw a steady erosion of the idea of reunification as a loose federation. On the 1 st January 1960 East Cameroon became a sovereign State, and a member of the United Nations. There was no prior agreement on the formulation of a federal constitution with West Cameroon. The UN had ruled out separate sovereignty for West Cameroon and imposed the choice between independence by joining Nigeria or by reuniting with the Cameroon Republic. Hence, equality of status between East and West Cameroon in subsequent negotiations was rendered impracticable. Unwittingly, West Cameroon had stayed behind the tide of reason and common sense; henceforth the current moved resolutely against federalism. Also, civil strife caused much insecurity at the time East Cameroon gained independence and the necessity to co-operate closely with France to stabilise the regime did not augur well for a loose federal formula.

Political opportunism, cut-throat competition between West Cameroonian politicians and the threat of an immediate British withdrawal dealt the final blow to the idea of a loose federation. Foncha and Endeley remained at daggers drawn before and after the plebiscite. Dirty politics was the order of the day and only the presence of British security forces imposed some restraint. It was certainly not in Foncha's political interest to involve Endeley's party closely in the process of federalising the union between East and West Cameroon. Foncha feared that the opposition in West Cameroon would put a wedge between him and Ahidjo. Accordingly, Foncha restricted the joint East and West Cameroon constitutional discussions to the two governing parties.

However, this did not go unchallenged even within Foncha's party. His deputy, Augustin Ngom Jua, led a faction of the KNDP who felt that Foncha had gone too far in isolating the opposition on a matter that concerned all West Cameroonians. Opposition to Foncha's leadership both within and outside his party was so strong that Ahidjo passed from being a negotiating partner to an arbitrator between disputing West Cameroon politicians. Thus the fact that Foncha could not dominate politics in West Cameroon, as Ahidjo had done in East Cameroon, was a serious handicap to equality in any constitutional negotiations. It left Ahidjo as the single strong man in the political life of Cameroon, free to apply his own interpretation to the federal notion.

Four months after the plebiscite results in favour of reunification between East and West Cameroon became known, Ahidjo summoned the Foumban Constitutional Conference (Johnson 1970: 169-185). The Conference was to discuss and agree on a federal constitution which would bind all Cameroonians with effect from the 1 st October 1961. It offered one last chance for the protagonists of the loose federal system. But the fact that it was Ahidjo who had chosen the timing and setting of the Conference, fixed the agenda, and summoned the delegates, made the meeting to all intents and purposes Ahidjo's Conference.

The central issue at the Conference concerned the nature of the central government and its relationship with the state governments. Ahidjo was unwilling to accept suggestions which weakened the dominant position he had already acquired in the constitution of the Republic of Cameroon. Only a constitution with a strong central government was acceptable in view of current political unrest and threats to national sovereignty by Ahidjo's political opponents (Johnson 1970: 180). He further insisted that national interest should take precedence over sectional interest.

A major problem which destabilised the West Cameroon delegation was the fact that they were seeing, for the first time, Ahidjo's constitutional package for a strong central government, with only residual powers for the federated State. Overwhelmed by 'brotherly sentiments', the West Cameroon delegates ignored their embarrassment and agreed to examine the proposals on the spot. As if further to humiliate them, the West Cameroonians were obliged to meet in separate sessions from the East Cameroon delegates for the five days that they were in Foumban. Under such circumstances there was no serious bargaining. There was too little time and agreement was expected immediately. Coming so soon after the plebiscite campaigns, the West Cameroonian representatives approached the deliberations at the Conference from established party positions and relied too little on experts. Moreover, there was complete unanimity in the East Cameroon delegation for a strong central government. In many ways, then, the Foumban Conference was used to persuade the protagonists of a loose federation to accept a strong central government for a united government which was already a fait accompli .

Romanian leader Ceausescu and Ahidjo

Ahidjo's actions were predicated on the readiness of France to participate in the socio-economic development of the federal Republic. Cameroon was one of France's most important trading partners in Central Africa, with long-range economic prospects. Since World War II, Cameroon had received huge French investments. At independence France had a relatively large colony and controlled the economy. The UPC challenge to French rule had necessitated a direct French military build-up in the territory. The new Cameroon government largely depended on French aid to maintain stability and peace (Bayart 1979: 240). Also, Ahidjo had signed secret military and intelligence pacts with France which would increase reunified Cameroon's dependence on France. France subsidised the Republic's budget by over 70% and for the most part ran the educational system. Hence, it was unthinkable for the ruling East Cameroonians to cut the umbilical cord with France so soon after independence, no matter how much pressure was brought from West Cameroon and anti-imperialist elements in the country.

The British left West Cameroon being unwilling to subsidise what they saw as a financially weak state. The Foncha government never undertook research into the economic issues to prove the contrary. This point, more than any other, worked against delegates fully pressing their case for a loose federation since they had to determine how their ideas were to be financed. The weakest point in favour of the loose federation at the constitutional 'negotiation' was therefore economic.

Aminatou Ahidjo, daughter of the first president Ahidjo

Nevertheless, the constitutional debates scarcely touched on economic issues. Too much time and effort was spent on political problems; trying to avert a totalitarian regime and what appeared to be French neo-colonialism. Indeed, the debates were carried out in an economic void, perhaps because it was felt that once political issues were resolved all the rest would follow on. This neglect is surprising since at base was the idea that reunification would serve as a catalyst for rapid economic development. Apart from the unfavourable Phillipson report (1959), there were no studies available to enable West Cameroon participants to make an accurate appraisal of the economic potential of West Cameroon. On the contrary, all believed that West Cameroon was a financial liability and the constitutional arrangements had to take this into account.

L'arrivée de S.E. M. El Hadj Ahmadou Ahidjo, Président de la République de Cameroun, à la 53e session de la Conférence internationale du Travail, Genève, 17 juin 1969.

In summary, we have seen that reunification was a potent political force which seriously affected the development of Cameroonian nationalism from the end of the Second World War until October 1961. It provided the leitmotif to attract co-operation between politicians in East and West Cameroon throughout the period. The concept of reunification developed from vague slogans to precise political structures bringing together East and West Cameroon in either a loose federal or a strong central government. The latter structure was finally adopted on the 1 st October 1961. Cameroonians have since lived under the unitary system irrespective of their colonial and cultural backgrounds. The achievements so far registered constitute one of the themes of Cameroon's contemporary history.

SOURCE:http://lucy.ukc.ac.uk/chilver/paideuma/paideuma-REUNIFI.html

Photo-source https://www.magnumphotos.com/C.aspx?VP3=SearchResult&ALID=2K1HRGMACLY

Pompidou`s visit

http://www.fonlon.org/

0 comments:

Post a Comment