“Eee, that man’s daughter was built; we can’t refuse to acknowledge what our eyes are showing us tho! Owiny has brought us such a beautiful girl; a girl who shines like the sun’s eye; who

is as pretty as a copper ornament” ~ Grace Ogot, The Strange Bride (1989)

“When you are frightened, don’t sit still, keep on doing something. The act of doing will give you back your courage.”~ Grace Ogot

Grace Emily Akinyi Ogot (born May 15, 1930) is a celebrated Kenyan writer of ethnic Luo origin credited for being the first African woman writer in English to be published with two short stories in 1962 and 1964. Ogot was not only an author and the first woman to have fiction published by the East African Publishing House, but an accomplished midwife, tutor, journalist and a BBC Overseas Service broadcaster. Grace Ogot was a founding member of the Writers' Association of Kenya.

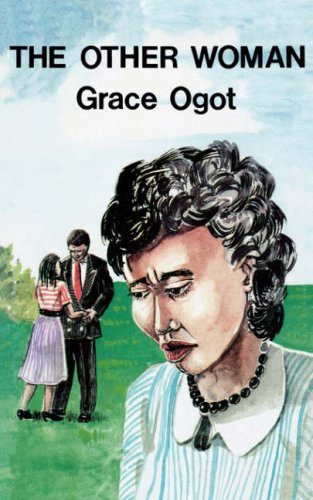

As a woman known widely for her anthologized short stories and novels, Ogot`s first novel The Promised Land (1966) was published in the same year as Flora Nwapa's Efuru and deals with the subject of migration. Her stories—which appeared in European and African journals such as Black Orpheus and Transition and in collections such as Land Without Thunder (1968), The Other Woman (1976), and The Island of Tears (1980)—give an inside view of traditional Luo life and society and the conflict of traditional with colonial and modern cultures. Her novel The Promised Land (1966) tells of Luo pioneers in Tanzania and western Kenya.

Grace Emily Akinyi Ogot earned a distinctive position in Kenya's literary and political history. The best known writer in East Africa, and with a varied career background, she became in 1984 one of only a handful of women to serve as a member of Parliament and the only woman assistant minister in the cabinet of President Daniel Arap Moi.

Ogot has also published three volumes of short stories, as well as a number of works in Dholuo. Her attitude towards language is similar to that of her fellow Kenyan, Ngugi wa Thiong'o's, but until recently her writing has not received the critical appraisal bestowed on Ngugi's writings. Her writing style is splendid in its evocation of vivid imagery; she captures the formalities of traditional African interpersonal exchanges, governed by protocol and symbolism. Indeed, Grace Ogot can undoubtedly be said to be one of Africa’s finest writers.

Ogot also worked as a scriptwriter and an announcer for the British Broadcasting Corporation’s East African Service, as a headmistress, as a community development officer in Kisumu, and as an Air India public relations officer. She appeared on Voice of Kenya radio and television and as a columnist in View Point in the East African Standard. In 1959 Grace Akinyi married the historian Bethwell Ogot of Kenya.

Ogot was born Grace Emily Akinyi to a Christian family on 15 May 1930 in Asembo, in the district of Nyanza, Kenya – a village highly populated by the predominately Christian Luo ethnic group. Her father, Joseph Nyanduga, was one of the first men in the village of Asembo to obtain a Western education. He converted early on to the Anglican Church, and taught at the Church Missionary Society’s Ng’iya Girls’ School. From her father, Ogot learned the stories of the Old Testament and it was from her grandmother that Ogot learned the traditional folk tales of the area from which she would later draw inspiration.

Emerging from the promised land in the anthills of the Savannah, Ogot attended the Ng’iya Girls’ School and Butere High School throughout her youth. From 1949 to 1953, Grace Ogot trained as a nurse at the Nursing Training Hospital in Uganda. She later worked in London, England, at the St. Thomas Hospital for Mothers and Babies. She returned to the African nursing profession in 1958, working at the Maseno Hospital, run by the Church Missionary Society in Kisumu County in Kenya. Following this, Ogot worked at Makerere University College in Student Health Services.

In addition to her experience in healthcare, Ogot gained experience in multiple different areas, working for the BBC Overseas Service as a script-writer and announcer on the program "London Calling East and Central Africa", operating a prominent radio program in the Luo language, working as an officer of community development in Kisumu County and as a public relations officer for the Air India Corporation of East Africa.

In 1975, Ogot worked as a Kenyan delegate to the general assembly of the United Nations. Subsequently, in 1976, she became a member of the Kenyan delegation to UNESCO. That year, she chaired and helped found the Writers' Association of Kenya. In 1983 she became one of only a handful of women to serve as a member of parliament and the only woman assistant minister in the cabinet of then President Daniel arap Moi.

In 1959, Grace Ogot married the professor and historian Professor Bethwell Allan Ogot, a Luo from Gem Location, and later became the mother of four children. Her proclivity towards story-telling and her husband's interest in the oral tradition and history of the Luo peoples would later be combined together in her writing career.

In 1962, Grace Ogot read her story "A Year of Sacrifice" at a conference on African Literature at Makere University in Uganda. After discovering that there was no other work presented or displayed from East African writers, Ogot became motivated to publish her works. Subsequently, she began to publish short stories both in the Luo language and in English. "The Year of Sacrifice" (later retitled "The Rain Came") was published in the African journal Black Orpheus in 1963 and in 1964, the short story “Ward Nine” was published in the journal Transition. Grace Ogot's first novel The Promised Land was published in 1966 and focused on Luo emigration and the problems that arise through migration. Set in the 1930s, her main protagonists emigrate from Nyanza to northern Tanzania, in search of fertile land and wealth. It also focused on themes of tribal hatred, materialism, and traditional notions of femininity and wifely duties. 1968 saw the publishing of Land Without Thunder, a collection of short stories set in ancient Luoland. Ogot's descriptions, literary tools, and storylines in Land Without Thunder offer a valuable insight into Luo culture in pre-colonial East Africa. Her other works include The Strange Bride, The Graduate, The Other Woman and The Island of Tears.

Many of her stories are set against the scenic background of Lake Victoria and the traditions of the Luo people. One theme that features prominently within Ogot's work is the importance of traditional Luo folklore, mythologies, and oral traditions. This theme is at the forefront in "The Rain Came", a tale which was related to Ogot in her youth by her grandmother, whereby a chief's daughter must be sacrificed to bring rain. Furthermore, much of Ogot’s short stories juxtapose traditional and modern themes and notions, demonstrating the conflicts and convergences that exist between the old ways of thought and the new. In The Promised Land, the main character, Ochola, falls under a mysterious illness which cannot be cured through medical intervention. Eventually, he turns to a medicine man to be healed. Ogot explains such thought processes as exemplary of the blending of traditional and modern understandings, “Many of the stories I have told are based on day-to-day life… And in the final analysis, when the Church fails and the hospital fails, these people will always slip into something they trust, something within their own cultural background. It may appear to us mere superstition, but those who do believe in it do get healed. In day-to-day life in some communities in Kenya, both the modern and the traditional cures coexist.”

Another theme that often appears throughout Ogot’s works is that of womanhood and the female role. Throughout her stories, Ogot demonstrates an interest in family matters, revealing both traditional and modern female gender roles followed by women, especially within the context of marriage and Christian traditions. Such an emphasis can be seen in The Promised Land, in which the notions both of mothers as the ultimate protectors of their children and of dominant patriarchal husband-wife relationships feature heavily. Critics such as Maryse Conde have suggested that Ogot's emphasis on the importance of the female marital role, as well as her portrayal of women in traditional roles, creates an overwhelmingly patriarchal tone in her stories. However, others have suggested that women in Ogot’s works also demonstrate strength and integrity, as in “The Empty Basket”, where the bravery of the main female character, Aloo, is contrasted by the failings of the male characters. Though her wits and self-assertion, Aloo overcomes a perilous situation with a snake, whilst the men are stricken by panic. It is only after she rebukes and shames the men that they are roused to destroy the snake. In Ogot’s short stories, the women portrayed often have a strong sense of duty, as demonstrated in “The Rain Came”, and her works regularly emphasise the need for understanding in relationships between men and women.

Prior to Kenyan Independence, while Kenya was still under a Colonial regime, Ogot experienced difficulties in her initial attempts to have her stories published, stating, "I remember taking some of my short stories to the manager [of the East African Literature Bureau], including the one which was later published in Black Orpheus. They really couldn't understand how a Christian woman could write such stories, involved with sacrifices, traditional medicines and all, instead of writing about Salvation and Christianity. Thus, quite a few writers received no encouragement from colonial publishers who were perhaps afraid of turning out radical writers critical of the colonial regime."

She was interviewed in 1974 by Lee Nichols for a Voice of America radio broadcast that was aired between 1975–1979 (Voice of America radio series Conversations with African writers, no. 23). The Library of Congress has a copy of the broadcast tape and the unedited original interview. The broadcast transcript appears in the book Conversations with African Writers (Washington, D.C.: Voice of America, 1981), p. 207–216.

Ogot’s family members shared her interest in politics. Her husband, served as head of Kenya Railways and also taught history at Kenyatta University. Her older sister, Rose Orondo, served on the Kisumu County Council for several terms, and her younger brother Robert Jalango was elected to Parliament in 1988, representing their family home in Asembo.

Publications

*Ber wat (1981) in Luo.

*The Graduate, Nairobi: Uzima Press, 1980.

*The Island of Tears (short stories), Nairobi: Uzima Press, 1980.

*Land Without Thunder; short stories, Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1968.

*Miaha (in Luo), 1983; translated as The Strange Bride by Okoth Okombo (1989)

*The Other Woman: selected short stories, Nairobi: Transafrica, 1976.

*The Promised Land: a novel, Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1966.

*The Strange Bride translated from Dholuo (originally published as Miaha, 1983) by Okoth Okombo, Nairobi: Heinemann Kenya, 1989.

SOURCE:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_Ogot

Days of Grace Ogot as a woman of culture and letters

By Prof Chris Wanjala, Nairobi, January 6 2013

Hon Grace Akinyi Ogot is woman who has powerfully influenced East Africa’s literary narrative and played a public role not only in medicine and community development but also in the country and parliamentary politics. She and her husband, Professor Bethwell Allan Ogot, have not only brought up a brilliant family, but they have stood by each other to foster creative and scholarly writing in our region. All the people who remember the sterling role of the East Africa Journal and its literary supplement which ran for decades as a publication of the East African Publishing remember the debates that characterized that publication. They will remember the well- documented polemics raised by the like of Okot p’Bitek, Taban lo Liyong, and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Grace Ogot’s own short story, Island of Tears, which followed the tragic demise of Hon. Thomas Joseph Mboya, was published in one of the issues of the East Africa Journal.

Dr Grace Ogot (right) presents a land title deed and other documents relating to the Odera Akang’o campus of Moi University to the then Higher Education minister, Prof Hellen Sambili, during a ceremony to hand over the campus to Moi University. Looking on is the Moi University Chancellor, Prof Bethwel Ogot, Dr Ogot’s husband.

Grace Akinyi Ogot has now published the story of her life entitled “Days of My Life: An Autobiography.“ Anyange Press Limited based in Kisumu City are the publishers of the 325 page account which traces Grace Ogot’s origin to Joseph Nyanduga, the mission boy who grew up in Nyanza, and after being orphaned sought his fortune in Mombasa where he was a locomotive driver, and Rahel Ogori, a mission girl. Nyanduga and Ogori were Christian converts and evangelists who defied the conservative Luo mores and traditions to chart out their lives and the lives of their children. There is a way in which the couple sacrificed a lot to deny themselves a working life in Mombasa to promote Christianity in Nyanza in the best manner possible. It is apparent in this story that when African cultures went against the practical existence of the couple, they defied them and went on with their lives as they thought best. There are, however, instances where Christianity, threatened their existence. In a manner of speaking, they modified conservative aspects of Christianity and went on with their lives.

Perhaps the best examples of their existential choices are there in the manner in which Joseph Nyanduga built his own home as a newly married man, away from his parents. The procedure of establishing one’s dala (home) away from one’s parents according to the Luo culture is explained in Grace Ogot’s novel, The Promised Land (1966). Joseph Nyanduga, however, goes against all the grain, acquires an education, travels to Mombasa where he is employed and when he feels the urge to evangelize among his people, he cuts short his career and returns home in Nyanza.

Days of My Life is a well-told story by one of Africa’s internationally acclaimed prose writer; it places the author in a unique position as far as the recent spate of autobiographies by erstwhile and practicing politicians in this country is concerned. It is the story of a woman who rises from the humble background of missionary life to soar high in the ranks of hospital nurses in Kenya, Uganda, and the United Kingdom. She goes against all the odds of racial prejudice among the colonial minority who did not expect Africans to excel in Medicine, and treats fellow Africans who are patients in her hands as respectable creatures against all the brutal practices where white health workers discriminated against their African patients. She has the best training in England and comes to work at Maseno Mission Hospital and Mulago hospital, Kampala. She is appointed Principal of a Homecraft Training Centre, becomes a councilor, a church leader, a business woman, and leading politician in the Moi era.

The book goes into the author’s education in colonial Kenya, revealing her leadership qualities, her high moral values, and her ability to learn new local languages. But perhaps the most instructive thing about the book is the strength of the love between Grace and the man she married. Throughout the account is the sobriety of their relationship and the way it informed her career development including writing. Their marriage was preceded by a protracted courtship period and an exchange of lengthy love letters. She had come from a background of strong story telling tradition which merged with her husband’s interest in oral history. He was then researching the history of the southern Luo drawing heavily from oral traditions. He readily appreciated her as a writer and pointed out the poetry in her letters to him. As the editor of Ghala: the Literary Supplement of the East Africa Journal he became one of early East African intellectuals to encourage her as a writer.

The book goes into the author’s education in colonial Kenya, revealing her leadership qualities, her high moral values, and her ability to learn new local languages. But perhaps the most instructive thing about the book is the strength of the love between Grace and the man she married. Throughout the account is the sobriety of their relationship and the way it informed her career development including writing. Their marriage was preceded by a protracted courtship period and an exchange of lengthy love letters. She had come from a background of strong story telling tradition which merged with her husband’s interest in oral history. He was then researching the history of the southern Luo drawing heavily from oral traditions. He readily appreciated her as a writer and pointed out the poetry in her letters to him. As the editor of Ghala: the Literary Supplement of the East Africa Journal he became one of early East African intellectuals to encourage her as a writer.

Mrs Ogot comments generously on her parents, relatives, members of the protestant church to which she belongs, her siblings and her fellow writers and literary intellectuals. There are stylistic flaws and errors of fact, dates, and even information on people, events and places in the book. Per Wastberg , the current Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Literature is a man. He has done a lot of work for African literature in Europe and Africa. But Grace Ogot writes: “In March 1961, I received a letter from a Swedish lady – a Miss Wastberg – author and journalist. She was on a tour of East Africa. In her letter, she told me that she was editing an anthology of African writing for publication in Sweden later that year. She had failed to discover any authors in East Africa. Eighteen countries in Africa would be represented in her book. She had heard from several people at Makerere University College, including Gerald Moore (a literary critic).”

The book is courageous and strong on politics and public administration of Nyanza Province and the entire country during the so-called Nyayo Era. It gives background information on assassinations on politicians in Nyanza and some of the people she replaced in her constituency. She gives accounts of how she and her husband went through a lot of pain to have access to President Moi in order to organize fund-raising meetings to develop her constituency. The book however shows how she badly let down writers and thespians as Assistant Minister for Culture and Social Services. She never worked to improve the working climate of the Kenya Cultural Centre in general and the Kenya National Theatre in particular.

Prof Chris Wanjala is chairman of Literature Department, University of Nairobi and National Book Development Council of Kenya.

source:http://www.abeingo.org/HTML_files/news_people.html

is as pretty as a copper ornament” ~ Grace Ogot, The Strange Bride (1989)

“When you are frightened, don’t sit still, keep on doing something. The act of doing will give you back your courage.”~ Grace Ogot

Grace Ogot, celebrated Kenyan writer of ethnic Luo origin, accomplished midwife, tutor, journalist and a BBC Overseas Service broadcaster and the first woman to publish a novel in East Africa and second in Africa after Nigeria`s Flora Nwapa.

Grace Emily Akinyi Ogot (born May 15, 1930) is a celebrated Kenyan writer of ethnic Luo origin credited for being the first African woman writer in English to be published with two short stories in 1962 and 1964. Ogot was not only an author and the first woman to have fiction published by the East African Publishing House, but an accomplished midwife, tutor, journalist and a BBC Overseas Service broadcaster. Grace Ogot was a founding member of the Writers' Association of Kenya.

As a woman known widely for her anthologized short stories and novels, Ogot`s first novel The Promised Land (1966) was published in the same year as Flora Nwapa's Efuru and deals with the subject of migration. Her stories—which appeared in European and African journals such as Black Orpheus and Transition and in collections such as Land Without Thunder (1968), The Other Woman (1976), and The Island of Tears (1980)—give an inside view of traditional Luo life and society and the conflict of traditional with colonial and modern cultures. Her novel The Promised Land (1966) tells of Luo pioneers in Tanzania and western Kenya.

Grace Emily Akinyi Ogot earned a distinctive position in Kenya's literary and political history. The best known writer in East Africa, and with a varied career background, she became in 1984 one of only a handful of women to serve as a member of Parliament and the only woman assistant minister in the cabinet of President Daniel Arap Moi.

Valentina Tereshkova and Grace Ogot. Chairman of the Committee of Soviet Women, and Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova (born 1937, left) meeting with Kenyan writer and politician Grace Ogot (born 1934). Tereshkova was the first woman in space, making her only flight on the Vostok 6 mission of 16-19 June 1963. Photographed in Moscow, Russia, on 1st July 1971.

Ogot has also published three volumes of short stories, as well as a number of works in Dholuo. Her attitude towards language is similar to that of her fellow Kenyan, Ngugi wa Thiong'o's, but until recently her writing has not received the critical appraisal bestowed on Ngugi's writings. Her writing style is splendid in its evocation of vivid imagery; she captures the formalities of traditional African interpersonal exchanges, governed by protocol and symbolism. Indeed, Grace Ogot can undoubtedly be said to be one of Africa’s finest writers.

Ogot also worked as a scriptwriter and an announcer for the British Broadcasting Corporation’s East African Service, as a headmistress, as a community development officer in Kisumu, and as an Air India public relations officer. She appeared on Voice of Kenya radio and television and as a columnist in View Point in the East African Standard. In 1959 Grace Akinyi married the historian Bethwell Ogot of Kenya.

Ogot was born Grace Emily Akinyi to a Christian family on 15 May 1930 in Asembo, in the district of Nyanza, Kenya – a village highly populated by the predominately Christian Luo ethnic group. Her father, Joseph Nyanduga, was one of the first men in the village of Asembo to obtain a Western education. He converted early on to the Anglican Church, and taught at the Church Missionary Society’s Ng’iya Girls’ School. From her father, Ogot learned the stories of the Old Testament and it was from her grandmother that Ogot learned the traditional folk tales of the area from which she would later draw inspiration.

Emerging from the promised land in the anthills of the Savannah, Ogot attended the Ng’iya Girls’ School and Butere High School throughout her youth. From 1949 to 1953, Grace Ogot trained as a nurse at the Nursing Training Hospital in Uganda. She later worked in London, England, at the St. Thomas Hospital for Mothers and Babies. She returned to the African nursing profession in 1958, working at the Maseno Hospital, run by the Church Missionary Society in Kisumu County in Kenya. Following this, Ogot worked at Makerere University College in Student Health Services.

In addition to her experience in healthcare, Ogot gained experience in multiple different areas, working for the BBC Overseas Service as a script-writer and announcer on the program "London Calling East and Central Africa", operating a prominent radio program in the Luo language, working as an officer of community development in Kisumu County and as a public relations officer for the Air India Corporation of East Africa.

Grace Ogot

In 1975, Ogot worked as a Kenyan delegate to the general assembly of the United Nations. Subsequently, in 1976, she became a member of the Kenyan delegation to UNESCO. That year, she chaired and helped found the Writers' Association of Kenya. In 1983 she became one of only a handful of women to serve as a member of parliament and the only woman assistant minister in the cabinet of then President Daniel arap Moi.

In 1959, Grace Ogot married the professor and historian Professor Bethwell Allan Ogot, a Luo from Gem Location, and later became the mother of four children. Her proclivity towards story-telling and her husband's interest in the oral tradition and history of the Luo peoples would later be combined together in her writing career.

In 1962, Grace Ogot read her story "A Year of Sacrifice" at a conference on African Literature at Makere University in Uganda. After discovering that there was no other work presented or displayed from East African writers, Ogot became motivated to publish her works. Subsequently, she began to publish short stories both in the Luo language and in English. "The Year of Sacrifice" (later retitled "The Rain Came") was published in the African journal Black Orpheus in 1963 and in 1964, the short story “Ward Nine” was published in the journal Transition. Grace Ogot's first novel The Promised Land was published in 1966 and focused on Luo emigration and the problems that arise through migration. Set in the 1930s, her main protagonists emigrate from Nyanza to northern Tanzania, in search of fertile land and wealth. It also focused on themes of tribal hatred, materialism, and traditional notions of femininity and wifely duties. 1968 saw the publishing of Land Without Thunder, a collection of short stories set in ancient Luoland. Ogot's descriptions, literary tools, and storylines in Land Without Thunder offer a valuable insight into Luo culture in pre-colonial East Africa. Her other works include The Strange Bride, The Graduate, The Other Woman and The Island of Tears.

Many of her stories are set against the scenic background of Lake Victoria and the traditions of the Luo people. One theme that features prominently within Ogot's work is the importance of traditional Luo folklore, mythologies, and oral traditions. This theme is at the forefront in "The Rain Came", a tale which was related to Ogot in her youth by her grandmother, whereby a chief's daughter must be sacrificed to bring rain. Furthermore, much of Ogot’s short stories juxtapose traditional and modern themes and notions, demonstrating the conflicts and convergences that exist between the old ways of thought and the new. In The Promised Land, the main character, Ochola, falls under a mysterious illness which cannot be cured through medical intervention. Eventually, he turns to a medicine man to be healed. Ogot explains such thought processes as exemplary of the blending of traditional and modern understandings, “Many of the stories I have told are based on day-to-day life… And in the final analysis, when the Church fails and the hospital fails, these people will always slip into something they trust, something within their own cultural background. It may appear to us mere superstition, but those who do believe in it do get healed. In day-to-day life in some communities in Kenya, both the modern and the traditional cures coexist.”

Another theme that often appears throughout Ogot’s works is that of womanhood and the female role. Throughout her stories, Ogot demonstrates an interest in family matters, revealing both traditional and modern female gender roles followed by women, especially within the context of marriage and Christian traditions. Such an emphasis can be seen in The Promised Land, in which the notions both of mothers as the ultimate protectors of their children and of dominant patriarchal husband-wife relationships feature heavily. Critics such as Maryse Conde have suggested that Ogot's emphasis on the importance of the female marital role, as well as her portrayal of women in traditional roles, creates an overwhelmingly patriarchal tone in her stories. However, others have suggested that women in Ogot’s works also demonstrate strength and integrity, as in “The Empty Basket”, where the bravery of the main female character, Aloo, is contrasted by the failings of the male characters. Though her wits and self-assertion, Aloo overcomes a perilous situation with a snake, whilst the men are stricken by panic. It is only after she rebukes and shames the men that they are roused to destroy the snake. In Ogot’s short stories, the women portrayed often have a strong sense of duty, as demonstrated in “The Rain Came”, and her works regularly emphasise the need for understanding in relationships between men and women.

Prior to Kenyan Independence, while Kenya was still under a Colonial regime, Ogot experienced difficulties in her initial attempts to have her stories published, stating, "I remember taking some of my short stories to the manager [of the East African Literature Bureau], including the one which was later published in Black Orpheus. They really couldn't understand how a Christian woman could write such stories, involved with sacrifices, traditional medicines and all, instead of writing about Salvation and Christianity. Thus, quite a few writers received no encouragement from colonial publishers who were perhaps afraid of turning out radical writers critical of the colonial regime."

She was interviewed in 1974 by Lee Nichols for a Voice of America radio broadcast that was aired between 1975–1979 (Voice of America radio series Conversations with African writers, no. 23). The Library of Congress has a copy of the broadcast tape and the unedited original interview. The broadcast transcript appears in the book Conversations with African Writers (Washington, D.C.: Voice of America, 1981), p. 207–216.

Ogot’s family members shared her interest in politics. Her husband, served as head of Kenya Railways and also taught history at Kenyatta University. Her older sister, Rose Orondo, served on the Kisumu County Council for several terms, and her younger brother Robert Jalango was elected to Parliament in 1988, representing their family home in Asembo.

Publications

*Ber wat (1981) in Luo.

*The Graduate, Nairobi: Uzima Press, 1980.

*The Island of Tears (short stories), Nairobi: Uzima Press, 1980.

*Land Without Thunder; short stories, Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1968.

*Miaha (in Luo), 1983; translated as The Strange Bride by Okoth Okombo (1989)

*The Other Woman: selected short stories, Nairobi: Transafrica, 1976.

*The Promised Land: a novel, Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1966.

*The Strange Bride translated from Dholuo (originally published as Miaha, 1983) by Okoth Okombo, Nairobi: Heinemann Kenya, 1989.

SOURCE:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grace_Ogot

Days of Grace Ogot as a woman of culture and letters

By Prof Chris Wanjala, Nairobi, January 6 2013

Hon Grace Akinyi Ogot is woman who has powerfully influenced East Africa’s literary narrative and played a public role not only in medicine and community development but also in the country and parliamentary politics. She and her husband, Professor Bethwell Allan Ogot, have not only brought up a brilliant family, but they have stood by each other to foster creative and scholarly writing in our region. All the people who remember the sterling role of the East Africa Journal and its literary supplement which ran for decades as a publication of the East African Publishing remember the debates that characterized that publication. They will remember the well- documented polemics raised by the like of Okot p’Bitek, Taban lo Liyong, and Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Grace Ogot’s own short story, Island of Tears, which followed the tragic demise of Hon. Thomas Joseph Mboya, was published in one of the issues of the East Africa Journal.

Dr Grace Ogot (right) presents a land title deed and other documents relating to the Odera Akang’o campus of Moi University to the then Higher Education minister, Prof Hellen Sambili, during a ceremony to hand over the campus to Moi University. Looking on is the Moi University Chancellor, Prof Bethwel Ogot, Dr Ogot’s husband.

Grace Akinyi Ogot has now published the story of her life entitled “Days of My Life: An Autobiography.“ Anyange Press Limited based in Kisumu City are the publishers of the 325 page account which traces Grace Ogot’s origin to Joseph Nyanduga, the mission boy who grew up in Nyanza, and after being orphaned sought his fortune in Mombasa where he was a locomotive driver, and Rahel Ogori, a mission girl. Nyanduga and Ogori were Christian converts and evangelists who defied the conservative Luo mores and traditions to chart out their lives and the lives of their children. There is a way in which the couple sacrificed a lot to deny themselves a working life in Mombasa to promote Christianity in Nyanza in the best manner possible. It is apparent in this story that when African cultures went against the practical existence of the couple, they defied them and went on with their lives as they thought best. There are, however, instances where Christianity, threatened their existence. In a manner of speaking, they modified conservative aspects of Christianity and went on with their lives.

Perhaps the best examples of their existential choices are there in the manner in which Joseph Nyanduga built his own home as a newly married man, away from his parents. The procedure of establishing one’s dala (home) away from one’s parents according to the Luo culture is explained in Grace Ogot’s novel, The Promised Land (1966). Joseph Nyanduga, however, goes against all the grain, acquires an education, travels to Mombasa where he is employed and when he feels the urge to evangelize among his people, he cuts short his career and returns home in Nyanza.

Days of My Life is a well-told story by one of Africa’s internationally acclaimed prose writer; it places the author in a unique position as far as the recent spate of autobiographies by erstwhile and practicing politicians in this country is concerned. It is the story of a woman who rises from the humble background of missionary life to soar high in the ranks of hospital nurses in Kenya, Uganda, and the United Kingdom. She goes against all the odds of racial prejudice among the colonial minority who did not expect Africans to excel in Medicine, and treats fellow Africans who are patients in her hands as respectable creatures against all the brutal practices where white health workers discriminated against their African patients. She has the best training in England and comes to work at Maseno Mission Hospital and Mulago hospital, Kampala. She is appointed Principal of a Homecraft Training Centre, becomes a councilor, a church leader, a business woman, and leading politician in the Moi era.

Mrs Ogot comments generously on her parents, relatives, members of the protestant church to which she belongs, her siblings and her fellow writers and literary intellectuals. There are stylistic flaws and errors of fact, dates, and even information on people, events and places in the book. Per Wastberg , the current Chairman of the Nobel Committee for Literature is a man. He has done a lot of work for African literature in Europe and Africa. But Grace Ogot writes: “In March 1961, I received a letter from a Swedish lady – a Miss Wastberg – author and journalist. She was on a tour of East Africa. In her letter, she told me that she was editing an anthology of African writing for publication in Sweden later that year. She had failed to discover any authors in East Africa. Eighteen countries in Africa would be represented in her book. She had heard from several people at Makerere University College, including Gerald Moore (a literary critic).”

The book is courageous and strong on politics and public administration of Nyanza Province and the entire country during the so-called Nyayo Era. It gives background information on assassinations on politicians in Nyanza and some of the people she replaced in her constituency. She gives accounts of how she and her husband went through a lot of pain to have access to President Moi in order to organize fund-raising meetings to develop her constituency. The book however shows how she badly let down writers and thespians as Assistant Minister for Culture and Social Services. She never worked to improve the working climate of the Kenya Cultural Centre in general and the Kenya National Theatre in particular.

Prof Chris Wanjala is chairman of Literature Department, University of Nairobi and National Book Development Council of Kenya.

source:http://www.abeingo.org/HTML_files/news_people.html